Arts & Culture

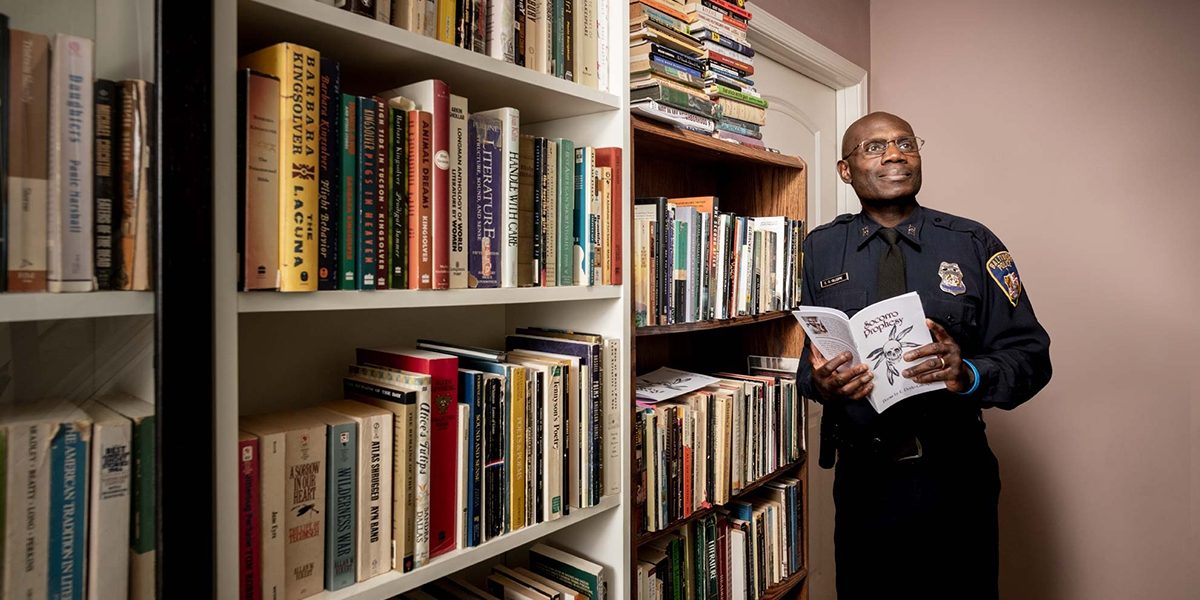

Cameo: Edward Doyle-Gillespie

We talk to “The Poet of the Baltimore Police Department”

You’re a Baltimore Police Academy instructor as well as a published poet. Which came first: police work or poetry?

I’ve always loved writing and reading, and I’ve always been fascinated by service. I started poetry in college, and in retrospect I wish I’d been an English major, but I became a history major because my plan was to become a military officer. I was in the Reserve Officers Training Corps at George Washington University, but I got injured, so when I graduated I looked toward education.

So you were a teacher before you joined the police force?

My first two years were in Baltimore City Public Schools, right out of college. I’d never been to a public school in my life. It was very much a fish-out-of-water situation. I had never seen an inner city. I had never seen a housing development. I had never seen that type of violence. It was nonstop culture shock, but it was very educational.

What kinds of situations did you face as a teacher that surprised you?

I would talk to the kids about what it was like to be in college, and I remember one student saying to me, “Did you have to fight a lot of people?” I said I didn’t fight with the people in college—I just went to class. There’s this moment of him staring at me like, “Why don’t you understand what I’m talking about?” and me saying, “Why would you ask that?” But, of course, I had to understand that a big part of his existence was establishing yourself through violence.

How did you transition into police work?

In 2011, I was in Johns Hopkins’ Master of Liberal Arts program and working for the university’s Success For All Foundation. One day I sat down to do my work, and my officemate said, “Hey, a plane hit the World Trade Center.” The second plane hit, and I thought, “Okay, I think this is my time to do something different.” 9/11 really got me focused. Four years later, I finished my master’s, I got my black belt, and I was in the first class of 2005 at the police academy. Now, I train officers. I teach classes on implicit bias, police legitimacy, hate crimes, white supremacist extremists, and sovereign citizens. I teach recruits about policing in Baltimore and the history of the city—good and bad.

How does your line of work influence your poetry?

Police work has worked its way into my writing quite a bit. I look for the poetry in the things that I see around me; there’s great raw material that just lays out in front of you. Milan Kundera, who wrote The Unbearable Lightness of Being, said that every culture has its kitsch and its shit. You can see both in doing police work. It’s like, here’s the human condition: What do you make of it?

How would you describe your three poetry collections?

The first two [Masala Tea and Oranges and On the Later Addition of Sancho Panza] are pretty free-flowing. My best friend read my work, and he said, “Your work tends to be about myth, violence, and sensuality.” And those two books flow through those three big themes. The third one is named Socorro Prophesy after a place in New Mexico that I found particularly fascinating, and it’s about myth, legend, and the culture of mythic storytelling.

Does being a poet make it difficult to relate to other police officers?

Police work includes such a diverse group of people. I’ve definitely had situations in which I didn’t relate well. I worked in one unit where there was a set idea amongst some officers that there are these cultural shibboleths that you must have to be an officer—or a male officer, or a black male officer—and if you don’t put those things forth then you can’t be included in the tribe. Whereas I’ve met other cops that read a lot. Once you scratch the surface, it’s amazing the backgrounds you find here. I’ve met artists and photographers, other writers, rappers. It’s a neat learning environment because it is so diverse.

What on-the-job moments have stood out as visual or auditory poetry?

I was walking up to the library at Penn North and there was a woman sitting there. I leaned down and said, “Are you okay?” She spoke to me in that muted tone of a hearing-impaired person, and she used sign language to say, “Yes, I’m fine. I’m waiting, thank you very much.” As we were talking, a trans woman walked up and started talking to us. Then, this young man with a sketch pad—it’s almost as if someone ordered this very diverse group of people from central casting—walked up and said, “Hold still, I’m sketching all of y’all.” And I thought, I want these people, all these people who are so diverse and so flawed and beautiful, to feel like they’re safe.