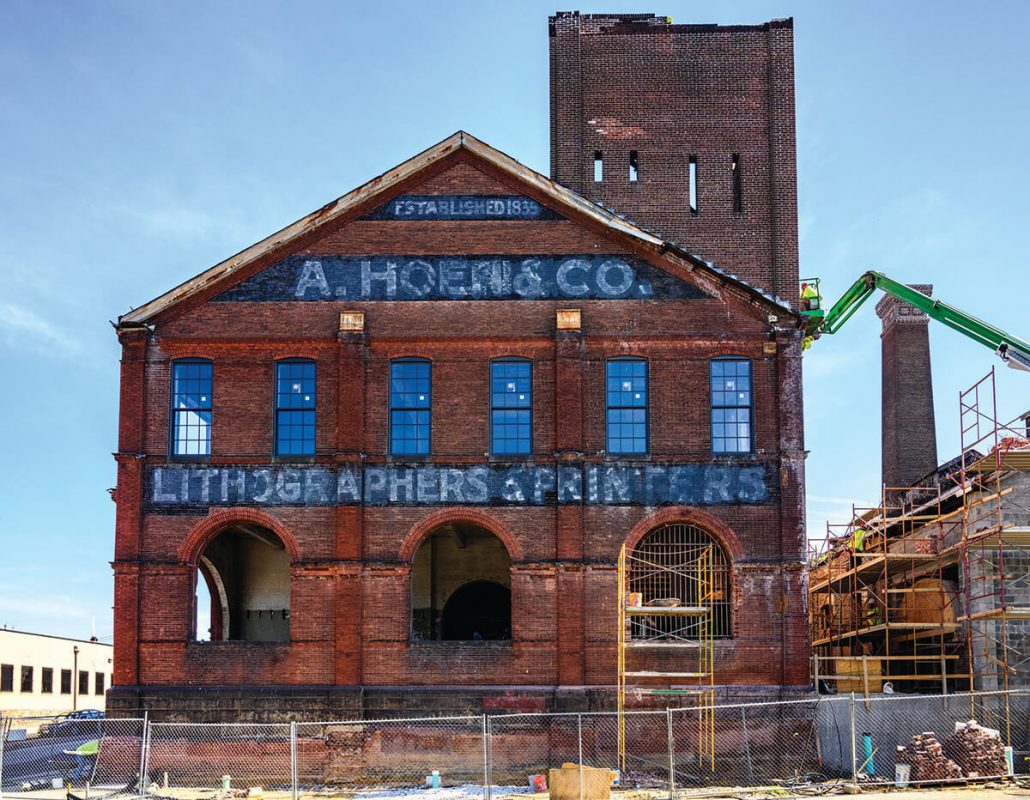

For Karen Stokes, CEO of Strong City Baltimore—a 50-year-old nonprofit that prides itself on fostering civic engagement, job creation, and strengthening neighborhoods—there is one word that comes to mind when detailing the once-decrepit state of the organization’s new home at the A. Hoen & Co. Lithograph Building in East Baltimore. She describes its former condition as a huge “blight” on the neighborhood.

“There were literally trees growing on it and it was boarded up,” Stokes says of the local Collington Square landmark. “There are generations of mice that lived in the building.”

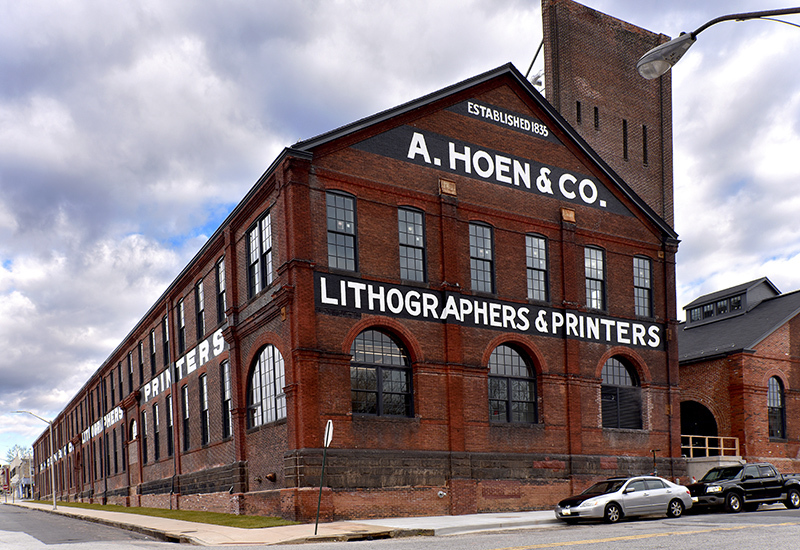

The A. Hoen & Co. Lithograph Building is more than 150 years old. It was most notably the home of the A. Hoen & Co. lithography business from 1902 to 1981. During its history, the innovative Baltimore company produced everything from National Geographic maps and food labels to Dr. Seuss books and Topps baseball cards.

“With all the places my father spent time, I feel his spirit most in that building,” says Tom Hoen, whose late father was at the helm of A. Hoen & Co. until it declared bankruptcy in 1981. “He recognized the value it had to Baltimore and to that community.”

The property, which surrounds an entire block on East Biddle Street, has been left dormant since the business shuttered nearly 40 years ago. Talk of its reconstruction dates back to 2016, when a 2018 target open date had been set, and the vision then has since evolved into what stands now.

However, with Strong City officially moved in as of this month, and more tenants on the way, the Hoen building is once again on its way to becoming a community anchor. This time around, the plan is for many different organizations to occupy the space and work together to create lasting change.

“This [project] has such potential,” Stokes says. “Strong City knows how to do neighborhood organizing. We are a place-based organization, so where we are physically located matters to us. We needed to show we had skin in the game in the neighborhood and physically be in a place where our mere presence could make a difference.”

The process to bring the building back to life involved nearly $30 million of private and public funding that included local, state, and federal capital and grants. For Strong City, the timing couldn’t have been better. When the organization—known as the Greater Homewood Community Corporation before 2015—recently turned 50, its staff began contemplating a move away from their longtime Charles Village headquarters. In its new home, Strong City will have a much larger space and multiple classrooms for its Adult Learning Center, which provides programs including GED studies, literacy training, and citizenship classes.

Stokes says the building won’t be completely full until the summer, when Associated Builders and Contractors, which will offer job training classes on site, City Life Community Builders, and Cross Street Partners, which oversaw the redevelopment of the building, take occupancy. Together, the organizations will form what will be known as the Center for Neighborhood Innovation (CNI), binding community leaders from all fields to solve problems in distressed neighborhoods.

“We want to find ways to create great new possibilities for neighborhood revitalization,” Stokes says. “Baltimore ought to be the best learning lab in the country for this.”

Strong City played a role in the renewal and commercial growth of Remington. In considering its move from the area, the organization saw an opportunity to take what it did in the now-bustling neighborhood—and what it does elsewhere in Baltimore—and apply it somewhere new.

That means educating the community about its efforts, eliminating housing vacancies, and collaborating with local businesses to help stimulate job growth. Stokes is encouraged by the recent rehabilitation of houses in the area in response to Collington Square activity, but cautions that it will take at least five years to see meaningful change.

“The first benchmark for us is doing a baseline analysis of where the vacants are—who owns what and how we can create a pathway for people to potentially buy and support small developers,” Stokes says. “We want to let people know that they can be a part of the rejuvenation of this neighborhood.”

Looking ahead, Stokes is excited to welcome all of the incoming tenants. There are also plans for a courtyard outside of the entrance, as well as a mini-museum in the lobby featuring lithographs and stone from the building’s past. It will be an homage to what the site once was, and point to what it can become.

“I’m excited by the idea that the physical plant that our family had been involved in for 150 years is being returned to a use that will provide value not only to the city, but to the community around it,” Hoen says. “It makes me smile to think that my father somehow feels that too. As a family, our only disappointment is that he isn’t around to see it.”