News & Community

In ever-dwindling numbers, survivors of the Nazi Genocide share their stories so the atrocity is never forgotten.

The word “Holocaust” draws a blank stare from many a millennial. Some 22 percent of young American adults aren’t familiar with the Nazi genocide of six million European Jews. According to a 2018 survey conducted by the Conference on Jewish Material Claims Against Germany, two-thirds haven’t heard of Auschwitz, the complex of concentration camps where some 1.1 million perished.

Bad news for us all—especially as anti-Semitism rises worldwide. In 2018, France alone reported a 74 percent increase in violence against Jews. In the past two years, synagogues in Pittsburgh; outside San Diego; and in Halle, Germany, have suffered deadly attacks.

The best remedy, says the Claims Conference, is education. Fortunately, the Maryland State Department of Education recently announced plans to expand the Holocaust curriculum in both middle and high schools.

“There aren't many of us left, and we won’t be here very long. Try to remember, so you can tell some of it to your children.”

Other groups have long been at it. “We teach it so that never again, ever again, such a catastrophe occurs to any group,” says Jeanette Parmigiani, director of Holocaust programs at the Baltimore Jewish Council. “Primo Levi, who was a Holocaust survivor from Italy, said, ‘It happened, therefore it can happen again.’ And it has happened again. Not the magnitude of the Shoah, but there have been other genocides. We try to educate and inspire students to be upstanders—a person who sees wrong and acts. It’s not just to protect Jewish people, it’s to protect everyone.”

Learning the awful truth is necessary. Learning it straight from a survivor, 75 years after the end of World War II, is rare. “We tell them, ‘Look, we are the last people to tell it to you,’” says Goldie Szachter Kalib, 88, of Pikesville. “‘There aren’t many of us left, and we won’t be here very long. Try to remember, so you can tell some of it to your children.’”

We sat down with three local Holocaust survivors to hear their stories, and had the rare opportunity to record their histories here.

Try, as Kalib urges, to remember.

Goldie Szachter Kalib

Pikesville, 88 years old

Goldie szachter Kalib HOLDS A PHOTOGRAPH of herself at the bergen-belsen displaced persons camp, taken after she was liberated at the age of 14.

“All Jewish children can't come to school tomorrow.”

We lived in Poland in a very small town called Bodzentyn. I was the youngest of the five, so I was more or less adored by my parents. My father co-owned a flour mill with my grandfather. In the wintertime he would make a sled out of one of the buggies, two horses, and a bell, and he would take out all my cousins. So we had a wonderful time. I was in first grade when the war started, and it didn’t take very long before the teacher announced all Jewish children can’t come to school tomorrow. The first few days, it was exciting. After a week or so, I started to understand. We had a balcony, and I looked down and right there, a German shot a girlfriend that I knew. Just for sport.

“There was gossip that the family was hiding a Jew. So I was hidden in a barn for three weeks.”

Food was so scarce. I saw people walking around with feet completely swollen, begging for food. My mother would try to cook soup and bake bread and give it out. My father had a friend, a bootmaker for the Germans in a munitions factory. The friend paid one of the Germans, and that German came in a covered truck and took our whole family to this city called Starachowice where this factory was. This friend was able to get ID cards for us as workers in the factory—except me. I was already 10, but I wouldn’t pass as a worker. An uncle of mine knew a lady called Surowjecka. He said she was a very fine human being. He suggested that my father ask her whether she would shelter me.

The day came I had to go with a man. We walked a long way. I did not cry; I pretended to be brave. And he asked me would I like some of the food that he had brought. Of course, my family was kosher, and I knew that all of that is traif. So, I thanked him very much, but I said I was not hungry. Finally, we arrived in the village. I went to sleep, and in the morning, this lady introduced herself and wasted no time. She wanted me to look more like a Polish Christian peasant girl. She started to lengthen my dresses, straighten my hair, and teach me the rituals of the church. I had to pretend to be this ‘Halinka,’ her niece from Krakow. But people recognized me. For example, one time a shoemaker from Bodzentyn. He said, “Even the shoes she’s wearing I made!” There was gossip that the family was hiding a Jew. So I was hidden in a barn for three weeks. Once Germans came and I was hidden in an empty beehive. The family had friends in another village who were rather poor. They were also very anti-Semitic. For three months, Mrs. Surowjecka paid them, with food, to keep me. Somehow, they never caught on that I am Jewish. I don’t think that they had even ever met a Jew.

Mrs. Surowjecka was able to get to my father. She explained that her life is in danger, and my life was in danger. Near my 12th birthday, my father arranged to have me illegally smuggled in to the labor camp with the factory. The laborers there had been spared when the rest of the town was liquidated by the Nazis. But in July 1944, the Germans apparently decided to abandon the camp. We were all transferred to Auschwitz. The train ride—how do I describe that horror? It was in the summer, windows shut. No air. No food. No water. My father and my younger brother did not survive the trip. When we got off it was a Sunday morning. I thought: Is this an insane asylum? There were these chimneys, such tall chimneys, from which you constantly smelled the stench of the burning flesh and you saw the fire. Somehow I was saved by a complex of miracles. I got so sick in Auschwitz. It’s hard to believe, but Auschwitz had a hospital. I was there for days and days. I don’t know if they tried to experiment on me or tried to save me. I was getting shots; from them I got a huge abscess under my arm. But somehow, I survived that.

“We saw Germans in the city, and they started to torture people.”

You’ve probably heard of Doctor Mengele. He picked out some women to go to the gas chambers and got my mother and me. And they put us in a windowless concrete room, dark, maybe 200 women, and Nazis came in to tease us. “Where do you want to be gassed? Here? Or in the gas chambers?” All the women yelled “Here.” So they would throw some white powder, but we all realized, after a few hours, we were alive. It was a hoax. One day a group of Germans came in and said: “Out.” We all thought, “Now we are going to the gas chambers.” Well, they took us all back to our barracks. We realized that the Russian army was very close, and they simply didn’t have time to do away with us. After that, we were sent on the death march to Bergen-Belsen. There were no crematoria in Bergen-Belsen. But there didn’t have to be, because people were dying. If you still had the strength to walk out of the barracks, say if you wanted to urinate, you had to walk on dead people. Literally. You couldn’t help it. You couldn’t walk out without walking on dead people.

Somehow my mother and my sisters survived that. On April 15, 1945, the British liberated us. My mother died three or four weeks after it ended. But I had grandfathers, cousins, aunts, and uncles—no one survived. Very often I am called to schools. I think: “Tell it as well as you can possibly tell it.” That’s all we can do.

FRED EMIL KATZ

TOWSON, 92 years old

Fred Emil Katz HOLDS A PHOTOGRAPH of himself from 1939, before he left his home in Oberlauringen, Germany.

“Going to and from school became a daily nightmare.”

I was born November 10, 1927. My 11th birthday was Kristallnacht—“the night of broken glass,” a violent, concerted attack on Germany’s Jews. We lived in a small village called Oberlauringen, in Northern Bavaria, roughly 90 miles east of Frankfurt. It’s a village of about 350 people, there were about 30 Jewish people living there. It was an Orthodox Jewish family. I very much remember standing next to my father in the synagogue. I knew every Jewish person in the village, I knew where they sat in the synagogue, I could tell you how they said their prayers. The first report from my first-grade teacher, my first year of school, it was one sentence: “Fred is fearful.” This was the first year of Hitler.

On November 9, 1938, all of the Jewish men in the village and the older children, including my brother, were taken away. My mother and I spent the night in the attic of the neighboring house. We heard people breaking into the house underneath us and our house, we heard everything being smashed up and yelling: “Where are the Jews?” We didn’t know whether we would make it through the night, my mother and me. The following morning, the noise stopped, and we went down, climbing over rubble that was our home.

After some weeks, the men came back. My brother and my father. And somehow the man next door was a little longer in coming back. When he did come back, I could not recognize him. His face was all beaten. We were so glad that they were alive. But they were awfully silent. They wouldn’t talk about what happened. They wouldn’t talk.

After Kristallnacht, it was crystal clear the Jews would not survive. My parents tried desperately to get out. We had relatives in America—in Dayton, Ohio. In 1937, these people had been able to sponsor my older sister, Trudy. As new immigrants, they didn’t have the funds to sponsor the rest of us.

“My form of survivor’s guilt is I can’t do the usual thing; I must do unusual things. Only then do I deserve to be around.”

My father was a butcher. He was a luftmensch—a man whose feet are firmly planted in the clouds. Many years later, a cousin of mine said that he made the best sausages and he read Shakespeare—a guy who had at best an elementary education. But he was not an accessible, verbal person. My mother was the opposite—very warm, outgoing, engaging, caring. I’m sure she gave me life twice. Once the usual way and the other when she arranged for me getting on the Kindertransport.

A group, which included Quaker, Jewish, and Christian members, had petitioned the British government to allow Jewish children to come to England. So 10,000 Jewish children were allowed to come. People ask me, was it difficult to leave your parents, and I say, “No.” It never occurred to me. I had only one thought in my head: “I must get away.”

My father didn’t have the money to come along to Frankfurt to the train station. That was one of the things that happened—we became poverty stricken. The killing of meat the kosher way became outlawed. That was my father’s livelihood. We had to go on welfare, Jewish welfare, because of that. Before that, we were ordinary burghers. My mother put me on the train and she stood outside, weeping. And I said to myself, “Why is she crying?”

The train went through Germany to Holland. We were then put on a ship across the channel to England. We were brought to London, then sent to a kind of a camp on the coast. Individual families came and picked themselves a child, but I wasn’t picked, so I ended up in a school called Bunce Court School in Kent. Virtually all the children and the faculty were traumatized. It was a congenial group of screwed-up people.

Before the war, you were able to write. After the war started in September 1939, you could send 25-word messages through the Red Cross. My mother was still telling me, “dress warm,” as if she was taking care of me.

For a long time, I didn’t know what had happened. When the war ended, I found out that on July 6, 1943, all the Jews from my village and the adjacent places were picked up and shipped off to Sobibór, the extermination camp in Poland. There were no survivors. It was only then that things hit me. They were murdered.

“You can't take survival for granted.”

When people drum into you, “you don’t deserve to live,” as was drummed into me, one of the most pernicious things is you might believe it. My form of survivor’s guilt is I can’t do the usual thing; I must do unusual things. Only then do I deserve to be around.

What is it about human ordinariness that is at work, so that decent people will do horrendous stuff? That’s what I’m addressing in my book Ordinary People and Extraordinary Evil. The mainstream is into “We must remember, so it won’t happen again.” That’s not good enough. My mission is to do a better job than that. I think I’m on the track to saving our species from destroying ourselves.

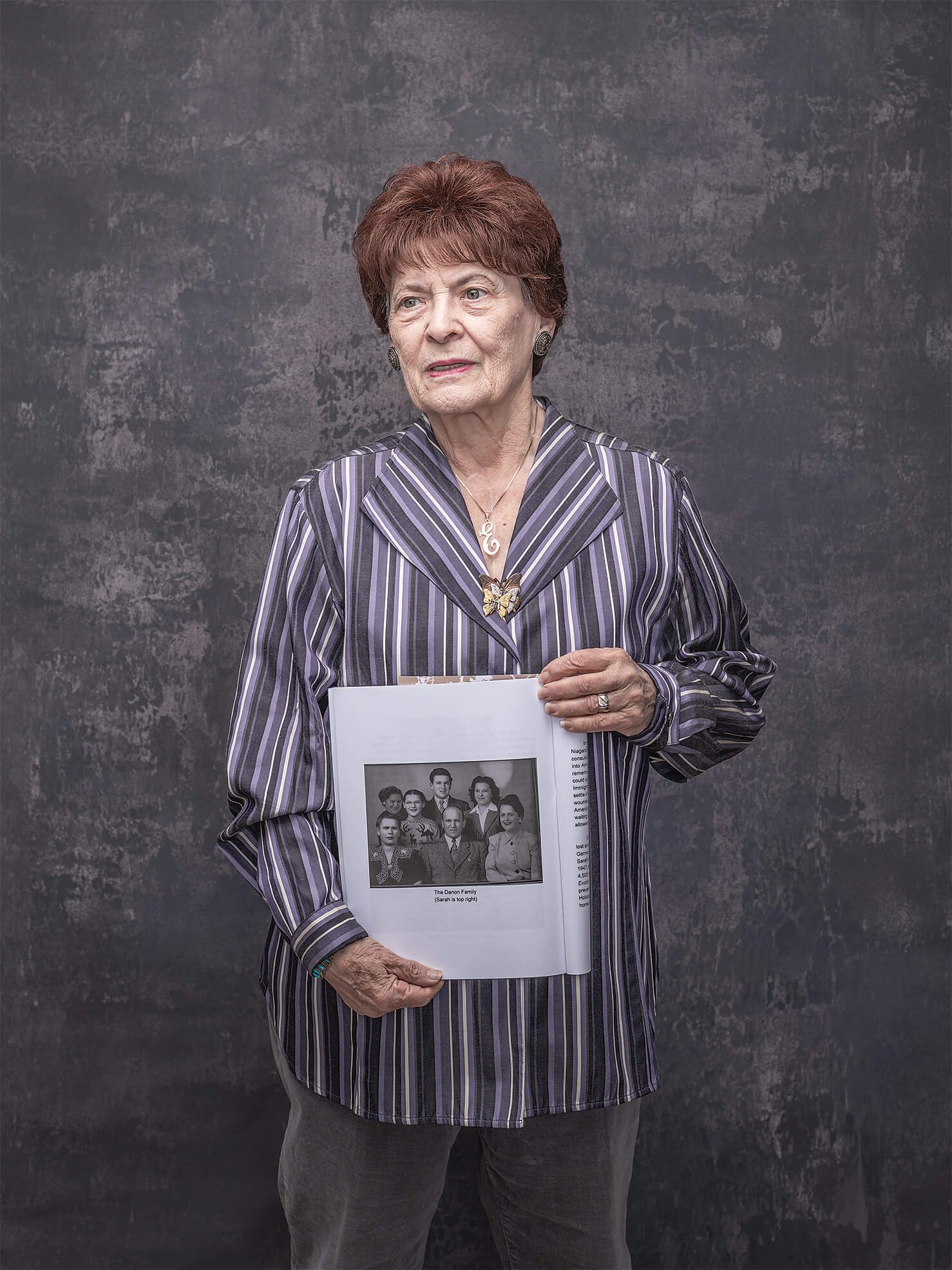

ESTHER KAIDANOW

LUTHERVILLE, 84 years old

Esther kaidanow HOLDS A PHOTOGRAPH of her family After she was liberated. They had just arrived in Philadelphia after beinG RELEASED FROM A REFUGEE SHELTER.

“They broke into the synagogue on a Friday night and beat up the people attending.”

Our neighborhood, I want to tell you, we had very few Jews. But we lived well with the neighbors. It’s a small city: Split, like a banana split, in what is now Croatia. We managed to live as we did, until this particular faction, the Ustacši—they were pro-Nazi—broke into the synagogue on a Friday night during services and they burned the holy books, the Torahs, in a bonfire. We came a little late. We saw that they were bayonetting people. We backed away. We went home a roundabout way. We passed by the rabbi’s house, and we saw that his face was slashed up and that many stores, including my uncle’s, were torn apart.

What can you do? This is what happened.

Neighbors, Christian neighbors, came and banged on our door and said, “The Nazis are coming.” Thinking they were only taking the men and they wouldn’t harm women and children, my father and my brother left. We saw the Nazis coming in on those bicycles with the side car. We saw people being hung, out by the promenade that we had. I saw that. It was a brutal thing.

My sister Sara, she practiced jumping out of a back window. She made me do it one time. She was preparing herself. We found out that they are about to collect women and children now. So, my gutsy sister, she was a tomboy type, Sara, she said we have to leave. My mother felt that it was her duty to save her home and her business; her husband had left it in her charge. My sister said, “We’re going to scare mother and tell her that if she doesn’t leave, we are going to go by ourselves.” She was about 12, I might have been 7. We went across a field, and my mother was yelling, “Wait, children, wait.” She was superstitious. She thought that God speaks to children. She said, “If you children think that that’s the thing to do, I’ll go with you.”

“We passed by the rabbi’s house, and we saw that his face was slashed up and that many stores, including my uncle’s, were torn apart.”

We wondered where to go. My sister said, “How about the milk maid?” We found our way to this small village, and the milk maid let us stay in a room that was not bigger than a single mattress. We never talked out loud, and we never showed ourselves, and she would bring us something to eat. It was about six months. Then she told us that somebody saw us and that she couldn’t keep us any longer. Her husband suggested: “Why don’t you go to the Partisans?”

Have you ever heard of Partisans? In English it doesn’t sound so good. When you’re partisan you’re biased. But that’s not the word. Partisans were the resistance fighters.

The Yugoslav Partisans allowed refugees to come even if they were not fighters. Once in a while they would get some animals from some farm, and they would cook it on a spit and then we would get a little bit, but most of the time we did have to fend for ourselves, and sometimes for days we didn’t have anything to eat. That was how it went for close to a year. The Partisans discovered that part of Italy was liberated by the British. The British had set up displaced persons camps for those who could get there. They said we had to go over this very bald crest of mountains and be on the beach and they would send rowboats. But the Nazis were all around. Four times, at least, in a terrible struggle, we came down to the beach and there was nobody there, so we had to go back and do it again. For days. One last time we came, and there were a few boats there, so we did manage to get to an island, me and my sister and my mother. We were told to wait and hide. A British boat came for us and we were like reborn. They dragged us up with ropes and one of the British soldiers gave me a candy bar.

“We saw people being hung.”

Already in 1944, President Roosevelt was told that he would look very bad in history if he did not do anything about the situation in Europe. Already most of the Jews had been killed. He decided he would bring 1,000 refugees to United States for safekeeping in Fort Ontario in Oswego, New York. My father and my brother applied, and they were accepted. When they heard we were alive, they asked if we could join them. And I guess America was always for reunification—if they accepted part of the family, they accepted the rest.

The ship was called the Henry Gibbins, an old troop transport ship. Half was wounded soldiers and half was our group—in the end it turned out 982, not the whole 1000. It was a long trip, almost a month because the war was still on. We had to hug the shores, we had to put on those yellow jackets, if we should drown, I guess. One time we were attacked. But they didn’t get us. We came to New Jersey—Hoboken. I looked at the skyline of New York. My mouth was wide open with the wonder of it all. Finally, we came in front of the Statue of Liberty. There was a rabbi who made a speech, that we should never consider ourselves lowly. Some people actually bent down and kissed the floor of the ship.