News & Community

The Land Before Time

Calvert Cliffs are Maryland’s hidden treasure.

On a late September day, Stephen Godfrey squints in the morning sunlight as it dazzles across the Chesapeake Bay. The sun-bleached beach stretches north and south as far as the eye can see, and while the tide is considered low, it laps at Godfrey’s ankles and licks up toward the top of his black wellies.

Still, he pushes on—down the beach, through the waves, under fallen trees, steadily over slimy, slippery rocks—all beneath the majestic cliffs that tower over him like a divine being. Finally, he reaches his destination, squatting down to inspect the base of the cliff.

As the churning surf crashes against the dark clay surface, the water washes away and reveals a relic in the ancient sediment—thousands of tiny white seashells—from millions of years ago.

“This is all you need to see to know that the Earth couldn’t have been created in six days,” he says, his bushy gray mustache turned up in a smile.

Eventually, the shells will tumble out of the cliff in near-perfect condition, their simple shapes ground into the sand, picked up by passersby, or donated to Godfrey’s collection as curator of paleontology at the Calvert Marine Museum in nearby Solomons Island.

Shells like these are prolific along this edge of the Chesapeake known as Calvert Cliffs. Stretching across some 30 miles of Southern Maryland shoreline through Calvert County, this natural wonder is a treasure trove of fossils, its bluffs and sands riddled with remnants of the Miocene Epoch, some dating as far back as 18 million years.

Somehow, right in our own backyard, this scenic splendor remains somewhat of a hidden gem, one that helps tell the story of our region’s past—and another world. Long before this beach became a destination for fossil collectors, history buffs, and outdoor enthusiasts, Calvert Cliffs began as an ancient ocean floor. As global temperatures fluctuated throughout the eons, sea levels rose and fell with the warming and cooling of the planet.

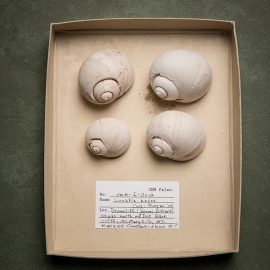

The Miocene was marked by a period of warmth, with Southern Maryland covered by a shallow, temperate sea, bound by tidal marshes, freshwater swamps, and bald cypress trees, not reaching land until modern-day Washington, D.C. Marine life flourished—predecessors of present-day sharks, whales, dolphins, and turtles, not to mention scallops, snails, clams, oysters, and a medley of other mollusks. As these creatures died, their bodies sank to the bottom and became buried under layer upon layer of sediment, preserved over the ages as if waiting for paleontologists like Godfrey.

At 57, Godfrey admits he didn’t always believe in science, let alone evolution. In fact, he grew up in Canada in an evangelical Christian household as a young-Earth creationist, believing that the Earth was created in six days some 10,000 years ago. Even as a nature lover—his bedroom filled with pinecones and animal bones—he pursued a career in paleontology with the hope of proving science wrong. Instead, while earning his Ph.D. in biology at McGill University in Quebec, he found cracks in his very core as he unearthed dinosaur footprints and ancient tree trunks buried in the North American soil.

Today, staring up at these staggering crags—some as high as 100 feet—as if they were a man-made map, Godfrey, who has studied Calvert Cliffs for nearly two decades, points out the years in the lines of silt and sand. The cliffs are split into three geological formations, or layers—the Calvert, Choptank, and St. Marys—ranging in age and composition.

“I like to think of it as a giant layer cake,” he says, standing beside the Calvert Formation, which is the oldest and deepest of the three. “The cliffs are what you would see if you cut out a giant slice.”

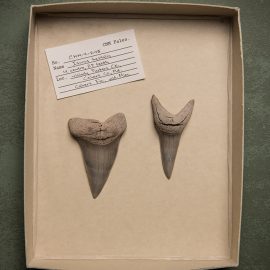

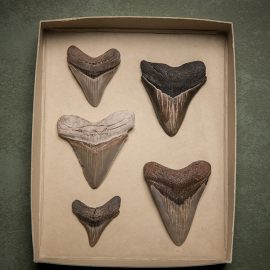

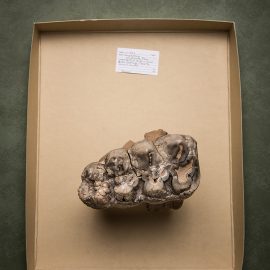

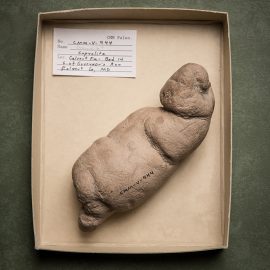

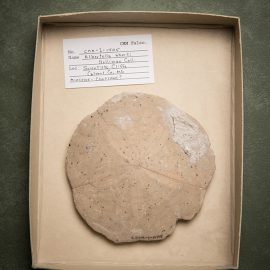

Fossil specimens at the Calvert Marine Museum; ancient shells are embedded within Calvert Cliffs; erosion slowly reveals ancient fossils buried in the face of Calvert Cliffs; Godrey explains the layers of Miocene sediment; the exposed cliffs range in age from 8 to 18 million years old. —Photography by Mike Morgan

To understand the history of Calvert Cliffs, one must go back even further, long before the birth of the Chesapeake Bay. Some 200 million years ago, the East Coast was connected to the supercontinent Pangaea.

“When we crashed into Africa, the Piedmont and Appalachian Mountains were gigantic, alp-like peaks,” says Godfrey. “When the continents pulled apart, the mountains began to erode as we pulled further away. They eroded and eroded and made the Atlantic Coastal Plain. Some of that mountaintop was taken off to make where we stand today.”

Over the millennia that followed, the Susquehanna River carved away at this low-lying land, flooding and receding with the climate, its little trail eventually backfilling to create the wide and splendid Chesapeake and, in turn, through waves and wind, the Calvert Cliffs.

But as the rising waters continue to work their erosive magic on the cliffs’ facade, the loss is also a gain as new fossils fall out of the receding ridge. Be it by shell, bone, or tooth, more than 600 Miocene species have been identified, representing nearly every animal phylum. That includes some 400 species of mollusks, like the iconic Ecphora gardnerae gardnerae, a caramel-colored spiral snail shell that is now Maryland’s state fossil. Even the occasional ancient land mammal has been discovered in this Darwinian domain—mastodons, rhinoceroses, tapirs, horses, dogs—most likely washed offshore during a violent storm or sudden flood.

Spotting something in the sand, Godfrey picks up a black, twig-like object, lifting the specimen into the air and rolling it around in his fingers before tapping it to his front tooth. “Ah,” he says, identifying the specimen as the tooth-like dental plate of a Miocene stingray. He knows its age because of the dark color, dense heft, and glassy timbre of its tap—all qualities obtained over the passage of time. Another means of distinguishing an ancient fossil from an average objet trouvé is rather simple: knowing what species no longer reside here or even exist.

A few steps later, he spies a puzzle-like piece of ancient leatherback turtle shell, followed by the base of a prehistoric dolphin skull. Up ahead, a man is slowly wading through the waves, a gnarled walking stick in hand, his curly salt-and-pepper tufts of hair windswept from the breeze. He is Pat Gotsis, a noted collector and friend of the museum, and as the two men exchange greetings, Gotsis shows Godfrey his morning’s finds, pulling out a pocketful of pristine sharks’ teeth—megalodon, mako, sand tiger, snaggletooth—which abound if you have the eye.

Clockwise from top left: Godfrey discovers the base of an prehistoric dolphin skull in the sand; erosion slowly reveals ancient fossils buried in the face of Calvert Cliffs; the waves of the Chesapeake Bay slowly eat away at the base of the cliffs; the small paleontology lab at the Ca.vert Marine Museum features aisles of filing cabinets filled with thousands of fossils. —Photography by Mike Morgan.

Since he retired this past September, Gotsis has watched the tides and walked the cliffs almost every day. At 55, he knows the terrain like it was his own property, having grown up here, collecting fossils along the banks since he was 10 years old. “It’s peaceful,” he says. “You never know what you’re going to find.”

Through the years, Gotsis has seen the cliffs evolve from his personal playground into a collectors’ paradise, and he has amassed a collection in the thousands along the way, including his most prized possession—the teeth of an extinct squalodon, or shark-toothed whale. “As the years went by, it just got to be second nature,” says Gotsis. “I thought I would grow tired of it, but I haven’t yet.”

Godfrey and his two-man team at the Calvert Marine Museum rely on a large network of beachcombers like Gotsis who report and donate fossils. Most of the cliffs are now private property, but many of the best collectors have approval for perusal from generous property owners. They’ve helped Godfrey locate giant finds, like the virtually complete skeleton of an ancient baleen whale. Still, public access points exist in multiple locations, including the beloved 1,300-acre Calvert Cliffs State Park. On any given day, from dawn to dusk, a handful, if not dozens of treasure seekers walk the strand, their gaze lowered and eyes focused on the miscellany in the sand. Some even sport shovels and sieves, but fossil collecting from beneath the cliffs is off limits, due to the danger of landslides. “A lot of these collectors have a real eye for it,” says Godfrey. “They spend more time along the cliffs than I do.”

The museum’s collection continues to grow, but out here, admiring the miles and miles of untouched beauty, looking across the bay to a side he cannot see, Godfrey knows the Calvert Cliffs are not infinite. The ebb and flow of the Earth’s climate also brings real concerns for property owners who reside along the cliffs. Every year, the water eats away at their shoreline—inches, sometimes feet—and edges toward their homes. Some residents are even rip-rapping their waterfronts to slow the rate of erosion, their rocky blockades forever cutting off accessibility for exploration and excavation. “It’s a resource that is dwindling,” says Godfrey. “We see our access to certain sections of the cliffs as sort of doomed.”

For that, he knows he has to keep going—there is so much more to discover. “There are still plenty of things we don’t understand about the universe,” says Godfrey. “We would be foolhearted to say we know all there is to know.”

Back in the basement of the Calvert Marine Museum, the small collections room is illuminated in fluorescent light, featuring aisles and aisles of filing cabinets filled with fossils, each drawer home to hundreds of razor-sharp sharks’ teeth or countless bits of blackened bone. At last count, the collection held more than 100,000 specimens.

Surrounded by boxes of yet-to-be-archived fossils, Godfrey gently holds an unknown object in his hands, brought in by a diver from a river in Virginia. It’s part of an ancient skull but features an unusual, spur-like knot he’s never seen before, and that’s a good feeling. Godfrey revels in being stumped. “That’s when the creative juices start to flow,” he says. “Like, this is something different. This is something new.”

Buried Treasure

Explore Miocene fossils from

the Calvert Marine Museum’s personal collection.