Former Baltimore Mayor Thomas D’Alesandro III, brother of Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, died at his home in North Baltimore Sunday. He was 90. The cause of death was complications from a stroke.

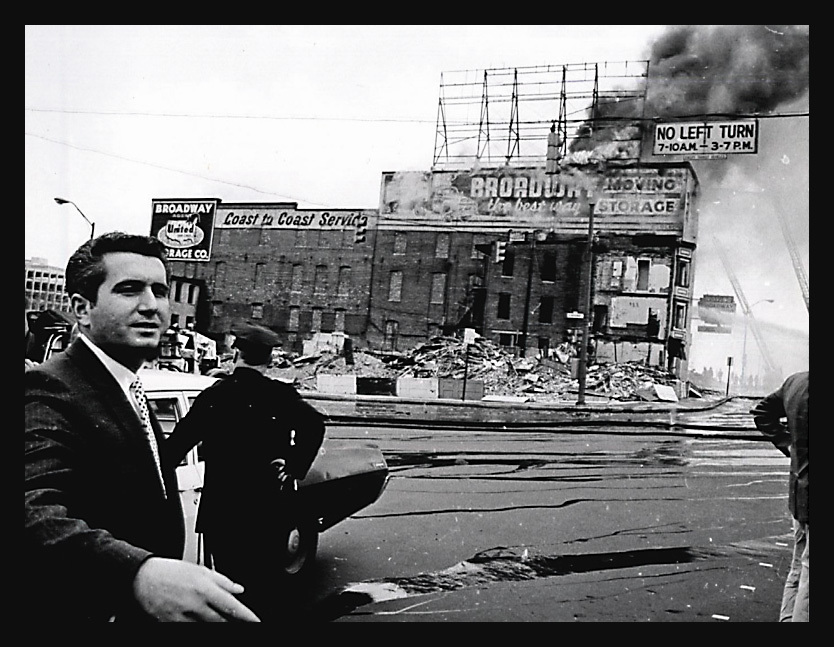

D’Alesandro III, affectionately known as “Young Tommy,” led City Hall from 1967-1971 and then surprised many by choosing not to run for reelection. His tenure coincided with a tumultuous period in the country that included the 1968 riots in Baltimore—which was already facing the effects of de-industrialization and suburban flight following the assassination of Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.

Considered a progressive on the civil rights issues of the day, he was the son of Thomas D’Alesandro Jr., the longtime mayor and congressman known as “Big Tommy” or “Tommy the Elder.” When he was president of the City Council, D’Alesandro III met with King in Baltimore, where the pair discussed civil rights legislation before the council at the time.

“Tommy dedicated his life to our city,” his sister, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, said in a statement. “A champion of civil rights, he worked tirelessly for all who called Baltimore home. Tommy was a leader of dignity, compassion and extraordinary courage, whose presence radiated hope upon our city during times of struggle and conflict.

“My husband Paul and our entire family are devastated by the loss of our patriarch, my beloved brother,” Pelosi continued, describing her oldest brother as “the finest public servant I have ever known.”

Current Baltimore Mayor Bernard C. “Jack” Young said D’Alesandro III will be remembered for his commitment to Baltimore and the “important strides” he made while in office, including “creating summer recreation programs for youth, removing racial barriers in employment and education, and laying the groundwork for what would become the world-famous Inner Harbor.”

Current City Council President Brandon Scott said that, as mayor, D’Alesandro III “understood the need to bridge communities and worked to eliminate racial barriers in City Hall.”

“There was absolutely no communication between the races, none whatsoever,” D’Alesandro III told NPR in 2008, describing the time he took office. “It was a segregated city. It was a Southern city.”

After graduating from then Loyola College in Baltimore, D’Alesandro III studied law at the University of Maryland School of Law in the city. He also served in the U.S. Army for four years before running for office. He was elected to the City Council in 1962, and the president of the Baltimore City Council in 1963. When he ran for mayor in 1967, he bested fellow attorney and eventual Orioles owner Peter Angelos in the Democratic primary.

D’Alesandro III appointed George Russell as his city solicitor, and Russell became the first black member of the Board of Estimates. He named Roland Patterson the first black superintendent of the city school system and appointed Baltimore’s first African-American, Rev. Marion Bascomb, to the city’s Board of Fire Commissioners.

“I know he was disappointed by the effect of the riots on what we were trying to do,” Joseph Lee Smith, a black member of D’Alesandro III’s staff, told The Baltimore Sun in 1998. “But I never noticed him being despondent. In the three and a half years that followed, I thought he was very determined and effective in getting the poverty programs in place.”

D’Alesandro III was preceded in office by Republican Theodore McKeldin, considered a liberal, and succeeded in office by William Donald Schaefer.

“We were trying to do it all—improve schools, housing, community development, policing,” Kalman R. “Buzzy” Hettleman, an assistant to D’Alesandro III, told Baltimore magazine last year. “Drugs weren’t a big issue, but policing was. [Donald] Pomerleau was the commissioner, and he was a controversial figure. Gruff. The mayor was under great pressure to appoint an African-American police commissioner [which didn’t happen until 1984 with Bishop Robinson].”

Robert Embry, president of the Abell Foundation, had been appointed by D’Alesandro III to head the then-new Department of Housing when the ’68 riots broke out. “So-called ‘blockbusting’ was in full swing in the Northwood and Edmondson Village neighborhoods, and that was a big issue [at the time],” Embry told Baltimore in a 2018 story on the 50th commemoration of the 1968 events.

D’Alesandro inspired many newcomers to city politics, City Councilman Bill Henry noted in Facebook post, including Henry’s father, a then-26-year-old activist whom the mayor named his youth coordinator and placed on his senior staff. “Looking back on the mayors of my lifetime, ‘Young Tommy’ stands out as having recognized the importance of all young people, especially in terms of their ability to move society forward when properly motivated,” Henry said.

His decision not to seek reelection, D’Alesandro III maintained, was not based on his experience dealing with the riots that broke out four months after his inauguration. Rather, he said it was largely an economic decision—he couldn’t afford to raise his five children while taking home $695 every two weeks.

He also admitted, however, that he did not love the job and public life the way his father did. He spent the rest of his career as a private practice attorney while remaining an informal political advisor to several local officials, including former Mayor Martin O’Malley.

His father, Thomas D’Alesandro Jr., served in Congress from 1939 to 1947, and then as mayor of Baltimore from 1947 to 1959. His mother, Anunciata “Nancy,” née Lombardi, D’Alesandro was an effective political organizer and helped him become Baltimore’s first Catholic mayor.

Recently, a D’Alesandro family portrait—painted when D’Alesandro III and Pelosi were still children and their father was assuming office in City Hall—has been restored and hung in Germano’s Piattini, the popular Little Italy restaurant across the street from their family’s rowhouse.

Last week, Baltimore also lost Congressman Elijah Cummings, a close colleague of Nancy Pelosi, who passed away at age 68.

When D’Alesandro III married Margaret “Margie” Piracci on June 8, 1952, some 5,000 people turned out to witness the occasion at the Baltimore Basilica. The fire department had to turn even more people way and two women reportedly fainted.

According to reporting from The Sun, the pope sent his blessings, President Harry Truman sent a silver tray as a wedding present, D’Alesandro III’s father, then mayor, served as best man, and his youngest sibling Nancy, later Nancy Pelosi, was a bridesmaid. It’s been said that it was as close to royal wedding as Baltimore has experienced.

“His life and leadership were a tribute to the Catholic values with which we were raised: faith, family, patriotism,” said Pelosi, who grew up with her brother and family in Baltimore’s Little Italy. “He profoundly believed, as did our parents, that public service was a noble calling and that we all had a responsibility to help others.”