Education & Family

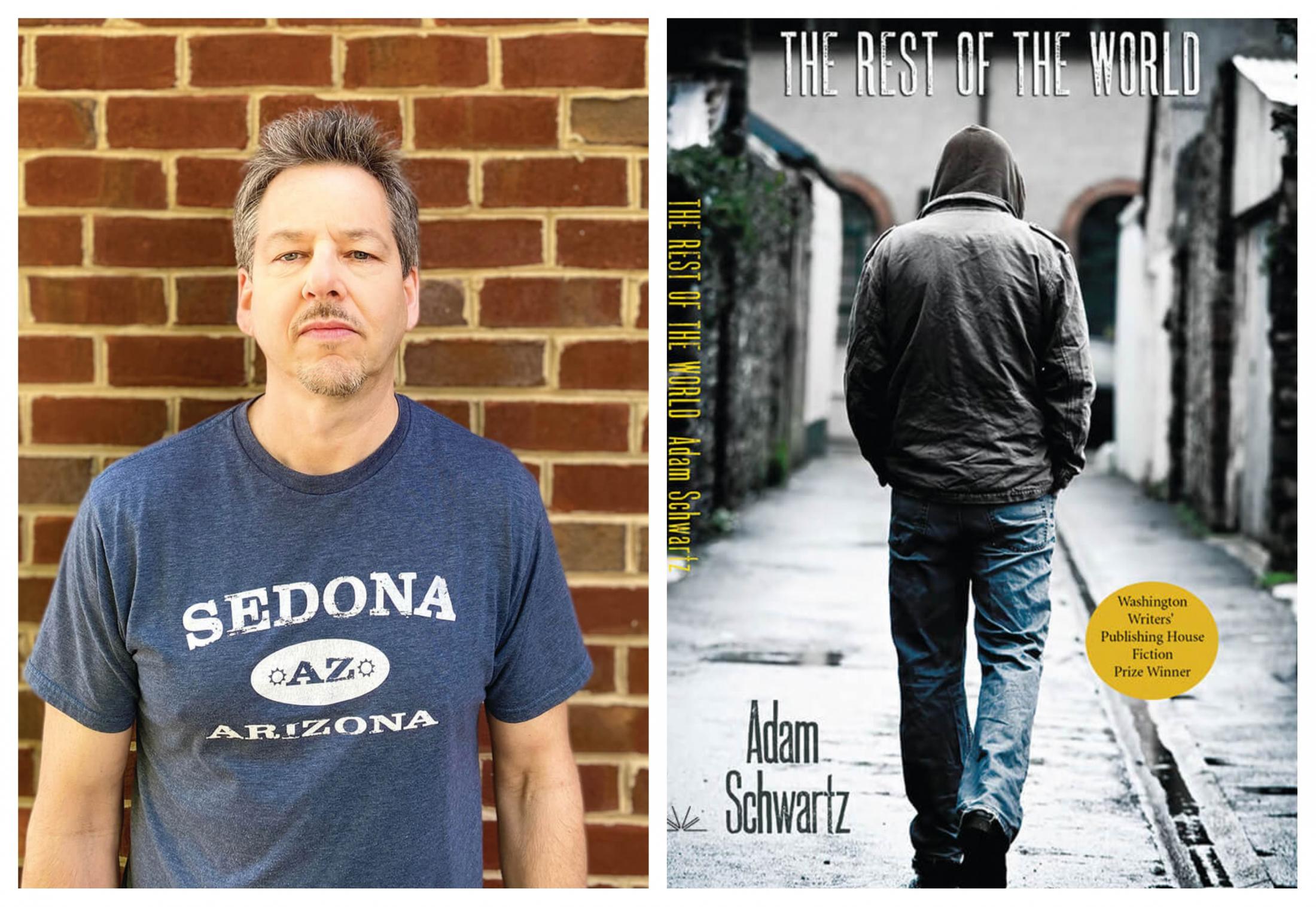

Adam Schwartz's New Book Captures the Resilience of Baltimore Youth

In his debut collection 'The Rest of the World,' longtime educator reveals the intense pressures this city exerts on many teens.

A Baltimore public school teacher for more than two decades, Adam Schwartz has spent the past 16 years at Career Academy, a small, alternative high school serving 11th and 12th graders in one of the original Goucher College buildings in Lower Charles Village. His students are typically older teenagers who left school for one reason or another—a family crisis, pregnancy, or juvenile arrest have derailed some—but have decided to return to their education. (The Mayor’s Office of Employment Development, which partners with Career Academy, occupies two floors above the school.)

It’s their complex lives, challenges, and coming-of-age in Baltimore journeys that provide the inspiration for Schwartz’s tightly woven character studies in his debut collection this fall, The Rest of the World (Washington Writers’ Publishing House 2020 Prize for Fiction). Schwartz reveals the intense pressures this city exerts on many teens. His empathetic stories of young adults in crisis illuminate the longings of the city’s youth, too often forced to navigate complex moral choices.

The teenage protagonists in your stories grow up in unstable circumstances. They are tough, but tenderly drawn characters at the same time.

Growing up in Baltimore can toughen and harden children. To protect themselves, some kids develop quiet, hard exteriors meant to project power and, maybe, repel trouble. But, of course, behind these flattened affects are teenagers with the same essential needs and vulnerabilities and fears and dreams as any of us. At school, most kids relax their guardedness within a few days or so. But this act of masking important parts of themselves makes some kids compelling, complicated figures.

The language of Baltimore City teens in the book is spot on.

Thank you—kids are interesting. The experiences they share, both the struggles and the triumphs, stick in my head, their voices stay in my ear, the striving they do against steep challenges evokes my hopes for them, and there are days when I’m carrying their voices around with me.

As a white male, are you ever conflicted about writing about the lives of Black youth? If so, how do you resolve those conflicts?

Some readers might see me as an imposter who hasn’t earned the right to write about the experiences of my characters. I’m not deaf to these kinds of criticisms. I think a lot about whether I’ve trespassed by creating characters whose struggles cannot be disconnected from our country’s abominable legacy of racial injustice—injustices from which I’ve been spared. Artists who perpetuate stereotypes or exploit the traditions of a culture should be condemned. Those who borrow from the pain of another group’s oppression without empathy or understanding should be called out. I don’t think I’m doing those things. My hope is that my stories honor the strength, will, and essential goodness so many Baltimore teens have shown me over the years.

What draws you to write about the lives of Baltimore teenagers?

Picture a kid coming up in a Baltimore neighborhood that was redlined—a particularly vile form of economic exclusion that often doomed neighborhoods to socioeconomic decline. Now imagine this neighborhood has also been hurt by disinvestment and municipal neglect and, as a result, offers few job opportunities; [consider that] it’s been socially isolated from other parts of the city, subjected to the policies of mass incarceration and endured years of corrupt policing; finally, suppose this neighborhood is pathologized by the local media for the purpose of enticing viewers with lurid crime coverage. In a variety of ways, the effects of these deep structural injustices land at the feet of children. As a teacher and a writer, I long to transcribe the resilience and determination of teens who sometimes cope with catastrophic obstacles.