Education & Family

Former NFL Player Joel Gamble Scores Wins Off the Field

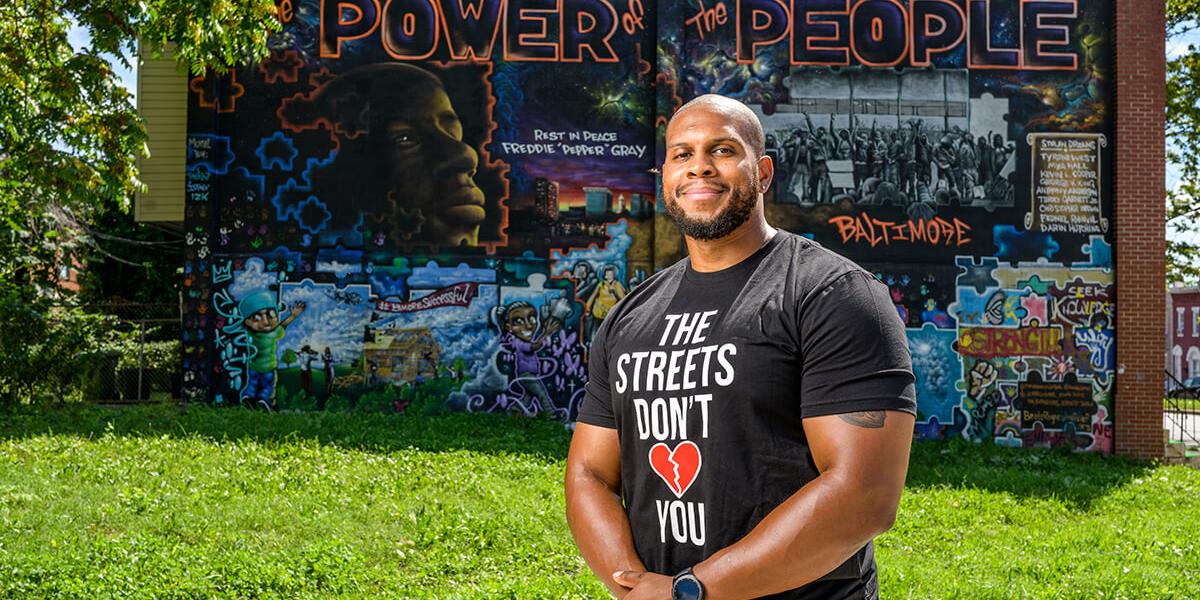

In the eyes of many, the Baltimore County teacher is as close to a real-life superhero as it gets.

When asked if he considers himself a superhero, former NFL player Joel Gamble laughs and says no. But he’s written a comic book featuring himself as a larger-than-life champion of kids who dons a magical jersey, fights bullies, and goes after urban villains such as gentrification and food deserts. He may not think so, but, in the eyes of many, he’s as close to a real-life superhero as it gets.

At 6-foot-2, 257 pounds, with 18 percent body fat, the West Baltimore native is a commanding figure with a sculpted bodybuilder’s physique and a magnetic smile. It’s no wonder he’s so respected by the students and faculty at Patapsco High School and Center for the Arts in Dundalk, where he is on staff as a special-education teacher.

And when he’s not teaching (or writing comic books), the 37-year-old Gamble—who was a two-way player at the city’s Carver Vocational-Technical High School before going on to play tight end and fullback in the pros—runs The Joel Gamble Foundation to help boys and girls develop athletic ability and social skills. “It’s a passion of mine, helping youth be more successful,” he explains.

He wrote his comic-book series, The Justice Duo, with Tavon Mason, another former NFL player. Gamble doesn’t want to share too many details from the yet-to-be-published work. But he says the Black Panther movie inspired him to pursue the project after he saw the impact of the billion-dollar box-office blockbuster on Black youth. “Kids need positive role models of color,” he says. “Growing up, we didn’t always see it.”

The Hanover resident credits his father, Ricardo Gamble, who worked in the community and coached a basketball league at Mount Royal Middle School on the city’s west side, as his role model. “I saw my dad mentoring boys in gangs,” he says. “I took after him. I took the torch back up.” His mother, Michelle, was also an inspiration, reading bedtime stories to her kids and getting the family through tough economic times when they were on welfare. “I admire her,” he says. “She made everything happen to take care of my sister and me.”

Gamble remembers his mom teaching him his ABCs and how to count before he started kindergarten. She saved his progress on audio tapes, so he could listen to his younger self and take pride in his growth. “She started me early,” he says. “That was huge.”

“KIDS NEED POSITIVE ROLE MODELS OF COLOR. GROWING UP, WE DIDN’T SEE IT.”

And though his parents divorced when he was young, he appreciates the morals and values they instilled in him at an early age. “I’ve been blessed, coming from West Baltimore and seeing the things I’ve seen,” he says. “I had an opportunity to play for the NFL and a platform to give back to other people.”

His sports ability and family also kept him away from West Baltimore’s drug corners. When he was growing up in the ’80s and ’90s, the neighborhood basketball courts were full of players, and kids tossed footballs in the streets. Everyone knew each other. The dealers left the athletes alone. The scene is different now, Gamble says: “It’s more transient.”

Still, he had friends who became gang members or did drugs. He estimates he’s lost about 10 people in his life to violence. One death hit him hard. A close high-school buddy was shot and killed. “I had to go to another funeral,” he sighs.

In The Justice Duo, Gamble and Mason are featured wearing their football jersey numbers (87 and 18, respectively). “We wanted to let people know that we are athletes who play more than football,” says Mason, who played with the New York Jets and is now a behavior specialist at Franklin Middle School in Reisterstown. The writing duo got a financial boost from a Kickstarter campaign, going over their goal of $3,000 to produce the comic series, Mason says. He and Gamble, who had each written a children’s book, connected over a love of encouraging kids to read. “I wanted to make reading fun again,” says Mason, a father of five in a blended family. “I wanted to get kids physically back to books.”

The ex-football players developed the Joel and Tavon Reading Tour, traveling to area libraries, and a friendship formed. The men had great fun developing the four-book, 10-page comic series together, each writing a different chapter and feeding off of each other for inspiration. Through a friend, they connected with a recent art-school graduate from Florida, Darrell Andrews Jr., who matched their words with illustrations. “It’s about real life, real issues,” says Mason. “We want to keep the kids’ attention.”

Gamble started his foundation in 2013 to connect with kids who don’t have resources or opportunities. He stepped up his involvement after the death of Freddie Gray, the 25-year-old Baltimore man who died in police custody in 2015. Besides offering football camps, scholarships, and mentoring programs, his foundation distributed more than 100 free laptops and tablets this summer to kids in need. Iyasia Costton, a 17-year-old senior at Career Academy in East Baltimore and the mother of a 2-year-old son, was one of the recipients of a Chromebook after writing an essay about why a computer would help her in school. “I didn’t have one,” she says. “I needed one to get the work done to get to college.”

Kenya Jacobs was grateful her son, Zion Williams, 14, received a computer thanks to Gamble’s foundation. “We don’t have access to a library, so this is very helpful,” she says. “It makes school less stressful.”

Jacobs was one of several family members gathered at Federal Hill Park on a balmy morning in late August, where a beaming Gamble—wearing a pandemic mask, black athletic pants, white sneakers, and a white T-shirt with a pale-gray JG Foundation logo on the front—gave out devices to the kids, complete with a grin and a fist bump.

“It’s been pretty cool,” he says of the computer giveaway. “A lot of kids don’t have access to Zoom or Google. There are students using their phones to turn in assignments. Others with siblings are sharing devices. The need is huge.”

Michael E. Haynie, founder and chairman of the Maryland Center for Hospitality Training, donated 20 computers so far to Gamble’s foundation. Its mission strikes a chord for the company that offers customer-service training to its adult clients. “I suspect the students are the kids of the parents [in our program] and trying to make better lives,” he says. “Joel is a humble servant. He’s very serious about helping kids.”

“HE LIKES TO HELP KIDS WHO REMIND HIM OF HIMSELF WHEN HE WAS GROWING UP.”

Gamble is in his second year of teaching at Patapsco High School—though he’s taught in the Baltimore County school system for eight years—and has already bonded with his charges. “Joel’s from Baltimore City, he’s a product of Baltimore City schools,” says Andrea German, the special-education department chair at Patapsco High School and Gamble’s supervisor. “He’s not flashy, he’s not loud. He walks the walk. He puts it into action.”

Patapsco High’s principal, Dr. Scott Rodriguez-Hobbs, agrees. “Joel’s job is to work with some of the more challenging students,” he says. “His background allows him to connect with students in a way none of us can.”

Gamble says working with kids in juvenile detention facilities before and after his days in the pros prepared him for his special-ed students, who may struggle with behavioral, developmental, and emotional issues. “All of them are eager to learn,” he says. “But they may have struggles in the classroom.”

He connects with the students on many levels, but they’re really impressed when they find out he played pro football, especially the student athletes. “They love that a former NFL player is in the school,” he says. “They want to play basketball with me, and they ask me to come to their basketball and football games.”

He’s happy to do both. Basketball was his first love while growing up. “Football grew on me,” he says. “I learned to love it.”

Gamble, who played briefly with the Philadelphia Eagles, Cleveland Browns, and Tennessee Titans as a tight end, knows what it’s like to go after a goal. He fought hard to get to the pros. He wasn’t drafted by a team after he graduated in 2004 from Shippensburg University in Pennsylvania with a degree in criminal justice, so he took a job as a corrections officer in a juvenile facility while continuing to focus on his workouts and football dreams.

Eager to get on the field, he eventually played in a professional indoor football league—joining teams with names like the Oklahoma City Yard Dawgz and Tennessee Valley Vipers—where he earned $250 for a win and $175 for a loss. He told The Sentinel newspaper in Pennsylvania in 2010 that money was so tight he had to give up his car. “Life was tough,” he said at the time. “Sometimes, you have to make sacrifices.”

When he finally got to the big time, he was thrilled. “The high point was the NFL, getting signed and going in the [Eagles] locker room and seeing my name on the locker—Gamble,” he recalls. “And seeing players like Donovan McNabb and Michael Vick and thinking, ‘I’m in a room with all these guys now.’ It was a huge moment in my life. The hard work paid off.”

He remembers his first catch in an NFL game, when the Browns went up against the Chicago Bears. “It gave me chills, hearing the crowd roar,” he says, excitement creeping into his voice at the memory. “It was second to none.”

But the bubble burst in 2011 when he became a free agent during the NFL lockout. He didn’t get picked up by a team when the work stoppage ended, and he headed back to Baltimore unsure of his next steps. He threw himself into keeping in shape and trying to get tryouts with NFL teams, including the Ravens. He also worked at a city residential facility for juveniles with behavior disorders and disabilities.

Despite his dedication and determination, his football days were over. “I was out a year,” he says. “Time passed. Once you’re out, it’s hard to get a tryout.”

But Gamble didn’t let the setback deter him from taking another career path. He transitioned into a behavior specialist, first at Berkshire Elementary School in Dundalk and then at Patapsco High, where he is a social emotional learning teacher. He helps students learn how to conduct themselves socially in the classroom and in life and how to manage their emotions. “He brings spirit,” says German, his supervisor. “He tells the students life is a process. You need to set goals. They really like him.”

She also appreciates how unassuming Gamble is. “What I love about Joel is that he does his work quietly,” she says. “To me, that’s the true mark of a leader.”

Gamble has also taken the lead with his workouts. “After football, I didn’t have the motivation,” admits Gamble, as he watched his weight fluctuate and his fitness level drop. “The journey now is to get in the best shape, even better than when I was playing.” He’s a regular at Gold’s Gym and Powerhouse Gym in Hanover, where he challenges himself with weight-training and cardio exercises.

His girlfriend, Jonene Ford, is a health and fitness coach and a nutritionist. They met at the gym. “He wanted to make changes to his diet,” she says. “He wanted to look more athletic.” Now, with Ford’s help, Gamble focuses on eating foods like egg whites, broccoli, and chicken. And while he’s strict about what he consumes, he makes a trip to Qdoba once a week. He has a weakness for cheese, he shares.

What impresses Ford most about Gamble is his dedication to helping others. “I’ve really never met someone with the heart to give back to the community from where they came,” she says. “He had a lot of obstacles in the way. He likes to help kids who remind him of himself when he was growing up. He does everything from the heart.”

To the kids he’s helping, he’s a larger-than-life champion with a heart—in other words, a superhero.