Education & Family

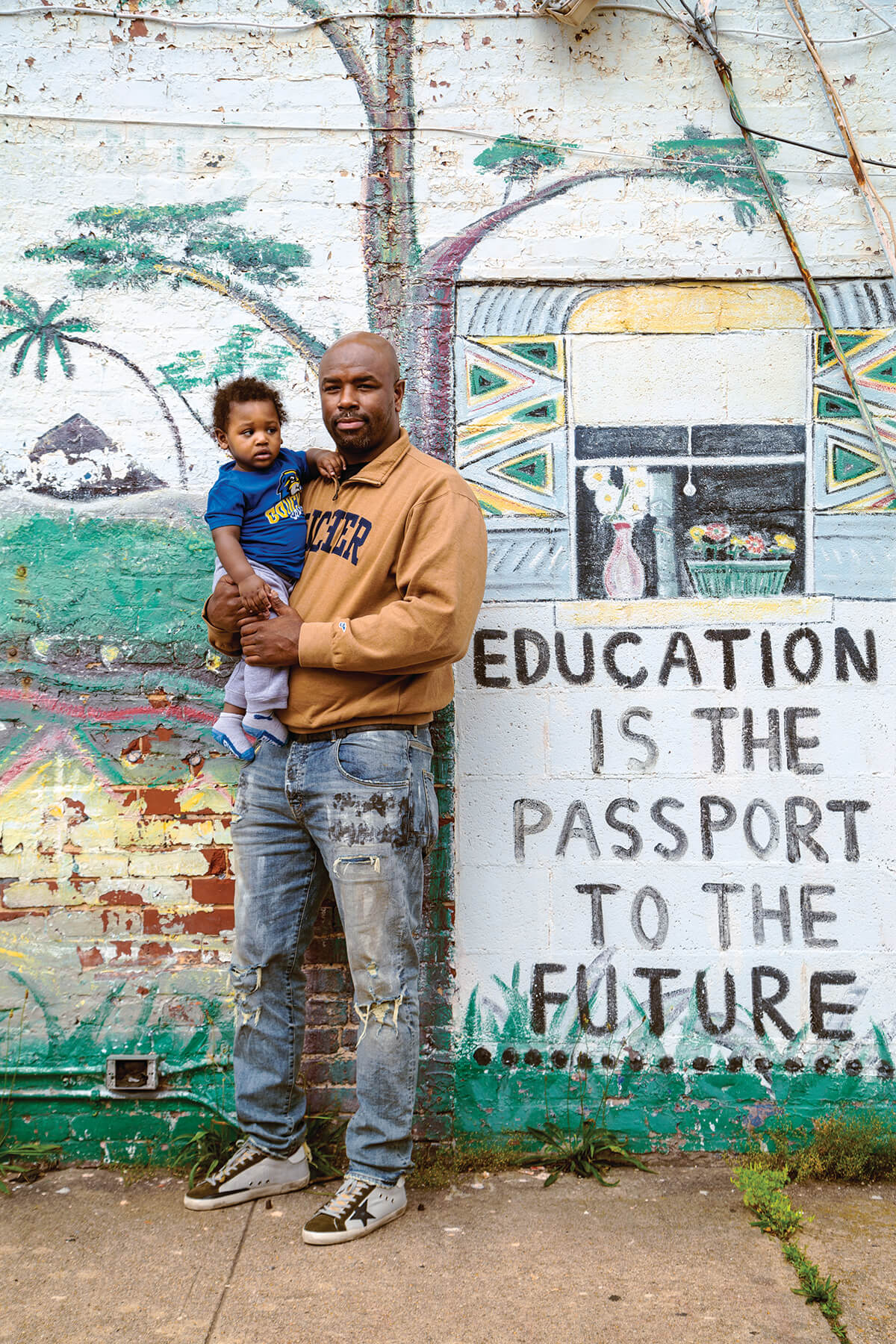

How Education in Prison Changed William Freeman’s Life

After earning a degree from The Goucher Prison Education Partnership, Freeman now empowers fellow formerly incarcerated students in his role at The Education Trust.

William Freeman III graduated from Goucher College in 2020 with a degree in sociology and anthropology. He earned 73 of those credits through the Goucher Prison Education Partnership while incarcerated for murder. Released from prison in 2018 after serving 20 years of his life-plus-20-years sentence, Freeman, 43, is currently a Bloomberg Fellow and master’s candidate at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health. He also works at The Education Trust, a national nonprofit that works to close opportunity gaps that disproportionately affect students of color and those from low-income families.

What was the path that led you to prison?

I was kicked out of the house at age 15. My mom couldn’t do much with me, and I was dismantling the structure of the household. I was shot at 16, and still not allowed to come home. Somehow, I graduated from high school, I was pushed through.

Substance abuse was part of my existence. I was using and espousing street life—I wouldn’t call it a life because you don’t do very much living inside of those parameters. You’re just existing and surviving at a very basic level. Your animal instinct is primarily what guides you. I was arrested in 1998, four days after my son was born.

What about being in prison changed you?

It was in prison that I read my first book from front to back: As a Man Thinketh, by James Allen. That’s a book I have in my library and reread from time to time. One of my favorite passages is: “Circumstances don’t make a man, they show him to himself.”

When I talk to young people, I talk about two kinds of education: the kind I got from Goucher, and the kind I got from the elders in prison—that’s home-grown, what you need to know to be firm in being who you are.

So, the prison elders were the father figures you hadn’t had growing up?

Absolutely. A father figure is important for young males because who do you emulate, who do you want to be like? Where I had lived a young life of wanting to fit in, in prison I was starting to get on this course of understanding my own purpose, my own self. It is truly pivotal.

Education has clearly changed your life. Can you describe how?

At one point I realized I was being blamed: “It’s 100 percent your fault, you made the decision.” But when I got involved in higher ed in prison, I learned that at age 25, the brain fully develops, the frontal part of the brain where you make your decisions. I was 19 when I was incarcerated. Those things were therapeutic for me, to allow me to forgive myself, and to be honest about being able to seek forgiveness from others.

Folks are not empty, just because we’re incarcerated, or low-income, or didn’t have a quality education. College equipped me with some tools. Sharp tools. Name-brand tools, where I could measure things that I thought. Where I could observe, put together a method to track the idea that I had, and then use those tools to get to an outcome.

Education gave me the tools to undo the idea that I had become something stagnant and unchangeable. It gave me a sense of pride, that I could come back from this thing that I had done.

Do you have thoughts about the root causes of violence in our society?

What’s not talked about enough is that it’s too easy for people who we know don’t have access to therapy to deal with their rage and their anger to get guns versus to get sustainable employment. Violence is not high because people feel like they’re being listened to, and they have a process to vent their grievances, and have solutions meted out to them that fix the trajectories of their lives. You get a suicide bomber out of a sense of hopelessness and a lack of resources. Like, I’m going to inflict as much pain as I can, on everyone around me, to make them see me.

How is the work you’re doing impacting the criminal legal system and those who are part of it?

I believe that if the U.S. criminal legal system was more oriented toward evidence-based reforms like education, instead of toward punishment, we would focus less on recidivism and more on creating space at the table for returning citizens. We must create opportunities for people to use their past experience to inform more humanitarian prison reform practices, like higher education.

Education Trust is building and empowering students who were formerly incarcerated to help them apply their personal experience to policy advocacy. We know that some so-called second chances are, in fact, people’s first chances. Creating space at the decision-making table for people who involuntarily forfeited their citizenship is imperative to deconstructing racism, reducing crime, and rebuilding marginalized communities.