Food & Drink

Two Sisters Become the Next Generation to Milk Cows at Broom’s Bloom Dairy

Only 15 dairy farms remain in Harford County, compared to 33 in 2002 and 54 in 1997.

It’s early June, and Kate Dallam, who owns Broom’s Bloom Dairy in Bel Air with her husband, David, is radiating with excitement. She has just created a new ice-cream flavor for the farm’s café.

“I need to take a photo now to get it up on Instagram,” she says, busily arranging a scoop of the chilled confection next to a single orange and a box of tea as she sets up the shot.

Customers, having taken notice of her photo shoot, ask if they can get a taste of the new offering, which is created by soaking Tazo Wild Sweet Orange tea bags in an ice-cream mix made from the farm’s milk and adding orange zest. “Refreshing” is the consensus.

Revenues from the store’s ice-cream sales have been a lifeline for the Harford County dairy farm, especially when economic times are tough. The rescue plan was put into effect almost 20 years ago when Kate Dallam, now 54, was trying to figure out how to pay the staff. She turned to an idea that had been, well, churning in her brain for some time and made it a reality: opening an ice-cream store.

Thanks to her husband, a brother, and a family friend, who built the country store (think an old-fashioned barn-raising), she ended up with an inviting space, which opened in December 2004. “My husband said he built the store to keep me out of the barn,” says Kate, laughing. It’s the kind of joke a couple who has been married 32 years makes.

At first, ice cream was the only product they sold at the store, but, a year later, Kate realized she had to expand the menu to keep the business viable. As the food items grew—from sandwiches and soups to mac and cheese and quiches—the cows and the family farm, where her 59-year-old husband was raised, thrived.

While there has been a drop in the number of dairy farms around the state and country, the 240-acre, nine-generation farm, which dates back to the 1700s, stays productive. Only 15 dairy farms remain in Harford County, compared to 33 in 2002 and 54 in 1997.

“It’s a tough environment,” says Republican state Sen. Jason Gallion, a Harford County beef farmer who represents parts of Harford and Cecil counties and is the agricultural specialist for Harford County. “A lot of local farms are not milking a lot of cows. It’s hard for them because the price they’re getting for their milk is not enough.”

Traditionally, dairy farms sell to milk cooperatives—farmer-owned groups that market the members’ milk and dairy products—says Gallion, a former dairy farmer. But now, aside from not getting enough money for their milk, many dairy farmers are faced with increased output costs to operate their farms, such as climbing diesel and fertilizer prices, he says. The rise in milk alternatives like soy, oat, and almond milk has also affected demand.

“The farms left today have reinvented themselves,” says Andrew Kness, the University of Maryland Extension agricultural agent for Harford County. “They’ve pivoted to direct market, instead of relying on dairy cooperatives.”

Only 15 dairy farms remain in Harford County, compared to 33 in 2002 and 54 in 1997.

For the Dallams, that reinvention meant opening their own milk processing plant in 2021 and making cheese and ice cream on the property. “It’s value-added agriculture,” Gallion says. “It supports local agriculture and brings people out to the farm.”

Other farms are following suit. Another operation in Harford County, Mt. Felix Farm, also turned to selling ice cream and cheese to support its farming efforts, naming the business Keyes Creamery after original owner Benjamin Keyes. And a third-generation horse

farm in Montgomery County, Waredaca Farm, decided to diversify by using farm-grown hops, herbs like lemon verbena and Thai basil, and honey from its apiaries to make beer at its farm brewery.

The Dallams hope their efforts will continue to keep the family afloat. Not only has the farm been in the family for many generations, mostly as a general farm, the couple has two daughters, Emmy, 26, and Belle, 22, who are stepping into the role of dairy farmers. They will be the second generation in a dairy business started by their parents at Broom’s Bloom in 1997.

“I always thought I could do something easier, like being a teacher or working at a nursing home,” says Emmy, who has a certificate in livestock management and an associate-arts degree in agribusiness. “But I knew I would always miss the farm, that I would always want to be on the farm, so I thought I should just do it.”

Belle, who recently graduated from Penn State, had no doubts about her future. “I always knew I wanted to come back here,” she says. “I wanted to go to college for agriculture and animal science and come back home.”

On a warm summer afternoon, the women take a break from their myriad chores, sitting at a picnic table at the farm store. They are bursting with their own plans for the farm. Emmy is already raising and butchering chickens and turkeys, and Belle hopes to breed Wagyu-Holstein cows in addition to dairy cows. “They are supposed to have excellent marbling and taste,” she says. “We’ll raise them for beef to sell here and to ship.”

Their other sister, Josie, 28, opted for the city lights of New York, though she spent plenty of time on the farm before going to graduate school to study children’s literature.

“It was an incredibly hard decision,” says Josie, who has a dual undergraduate degree in agronomy (field-crop science) and agricultural communications. “I was working full time in the ice-cream store, and I could see myself being satisfied with that, but I always wondered what it would be like to work in publishing. Then I had a moment when I realized I was 23 years old and thought, ‘Let’s go do it and figure out how it would work.’”

She also knew she had a backup plan.

“My family’s farm has been around for almost 300 years,” says Josie, a school and library marketing coordinator for HarperCollins Publishers. “I was pretty sure I could leave and try something else, and if it didn’t work, I could always come back.”

Broom’s Bloom has deep roots in Harford County. A Maryland Historical Trust report, detailing its historic significance, dates its settlement to 1747, when Isaac Webster built a house on the property. Since then, it has been run by direct descendants of the Webster-Dallam clan, who have continuously farmed the property, though both families settled in the county earlier in the 18th century.

The farm’s name is credited to John Broome, who was granted a land patent for the property in 1685. There are no records that he ever made it through the dense forests of the time to visit the acreage. After he died, his patent went to various people before ending up with the Websters.

The farm’s name is credited to John Broome, who was granted a land patent for the property in 1685.

The “Bloom” part of the name is open for interpretation. Some family members say it refers to flourishing crops. But a 1959 Baltimore Sun story about William Dallam, who was farming the property at the time, reported that the tract was named after a broom plant that was in bloom when the first family settled there. (The story also included a recipe for corn wine, so it could have been the wine talking.)

Before the Dallams inherited the land, it had been used as a general farm with some crops, one milk cow, sheep, hogs, and sometimes chickens, says Katy Dallam, who grew up on the property with her younger brother David and two other siblings. Their father died in a tractor accident when she was 16 and David was 8. The family was devastated but did what needed to be done. “My mother kept the farm going,” Katy says.

While Katy chose a different career path, David had one goal growing up. “He wanted to be a dairy farmer,” says his sister, who is a retired independent school administrator and English teacher. “It’s an incredibly hard job.”

Morning comes early at Broom’s Bloom. David heads to the processing plant, and Emmy and Belle turn on the lights to the cow barn around 5 a.m. for the first feeding and milking of the day. The 53 cows—a mix of black-and-white Holsteins, red-and-white Holsteins, and Guernseys—with names like Elsie, Daisy, and Ritzy, are standing at the ready or lying down on their water beds. The women gently clean the udders of each cow with iodine and attach pumps to pull milk from the teats, which goes directly to pipes and then is filtered. It ends up in a bulk tank until it is pumped to the processing plant for bottling. A gauge on the tubing shows when each cow is finished milking.

Then, the pumps are removed, and the udders are again rinsed with iodine. Emmy and Belle work on a few cows at a time as they move along two rows of the animals, each of which weighs about 1,300 pounds. As they proceed, a few cows who are still reclining get a firm pat on their haunches to move them to an upright position. One heifer, Erma, is a kicker and is slightly restrained during the milking. “She tries to eat the machine,” explains Emmy.

It’s not glamorous work. During the milking, the cows are peeing and pooping, which the women shovel into a drain system while adding more sawdust around the cows. But that’s just life on the farm. Music plays to calm the animals, and maybe Emmy and Belle, too. They prefer country music. During a recent milking, Steve Holy crooned “Good Morning Beautiful,” Easton Corbin belted out “Marry That Girl,” and Shania Twain sang “Up!” over a sound system, competing with giant, whirling, noisy fans that keep the barn cool.

Emmy and Belle work in unison while milking without much conversation, the way partners do when they share a daily chore. After the milking is complete at 6 a.m., Emmy feeds the calves, which are housed in another barn, and Belle washes the milking equipment. The cows go out to the pasture for a while.

As soon as the calves hear the clink of the metal milk pail Emmy is carrying, they move around excitedly. They know what’s coming: milk, fresh water, and grain if they’re old enough. The youngest calves each live in separate compartments until they are weaned. Emmy’s puppy, Penelope, a border collie/American Eskimo mix, tags along and sneaks a gulp of milk when Emmy isn’t looking.

The rest of the day is taken up with various projects. One day, the women put fly tags on the heifers, which Emmy describes as earrings with bug repellent that keep flies off their faces. Another day, the cows get their hooves trimmed, sort of a fancy bovine pedicure.

Emmy also spends part of every day caring for her chickens on a farm in Churchville, which the family also owns and uses to house about 70 heifers in their herd. She christened the business she started in 2018 as Homelands Poultry after the name of the farm, once owned by her mother’s family (and now owned by Emmy’s parents). Emmy also raises turkeys for Thanksgiving. She and her fiancé, Lucas Beavers, became licensed poultry butchers to save money instead of outsourcing the birds.

At 5 p.m., back at Broom’s Bloom, it’s time to feed and milk the cows again. Then, around 8 p.m., they get a final feeding.

“We call it tucking the cows in,” Belle says. “Then we turn out the lights, and we see them again in the morning.”

Emmy and Belle are used to long days at the farm. They started helping out at local farmers’ markets, selling the farm’s products, and working at the dairy store when they were a young age.

“My mom always tells customers that I’ve been washing dishes at the store since I could stand on a stool,” Belle says with a laugh. “I remember in sixth grade I had a weeknight shift.” When they were in eighth grade, they became involved in the milking process. “I think that’s when I became more useful,” Emmy says, smiling.

They also were part of the state and national 4-H, showing their cows at various events—and are familiar with the pain of parting with their animals. “We can only keep the cows as long as they’re productive enough to cover their expenses,” Belle says. “Then we have to sell them, which is really difficult. They are an expensive pet to keep.”

But there is one cow they couldn’t part with—Hazel—who is 13 years old. “She’s our mascot,” Belle says. “We’re only allowed to have one of those in our life.”

Several mornings a week, Emmy and her dad pasteurize and bottle the cows’ milk, in two large rooms with stainless-steel tanks, in the processing plant next to the cow barn.

On a recent morning, a plastic bag with 200 one-gallon plastic containers awaited the mostly automated process, where empty jugs are placed on a conveyor belt by Emmy, filled with milk, and capped before being placed in plastic crates, which are stored in a refrigerated room. The dairy bottles whole milk, 2 percent milk, and chocolate milk.

David Dallam goes about his duties quietly, moving from one piece of equipment to the next, checking temperatures for pasteurization, and squirting off the equipment with water. He’s more comfortable in the background doing the work he loves, according to his family. “He is really hard-working,” his sister Katy says.

Since retiring, Katy, who is widowed and lives in her own house on a piece of the family property, which is protected by the Maryland Agricultural Land Preservation Program, has become part of the milking operation. She affixes labels by hand to the milk jugs before Emmy and her father start bottling, estimating she can do about 1,000 labels a day in the four to eight hours a week she volunteers her time.

“This is the perfect job,” she says. “I can do it when I want to, and as much as I want to.”

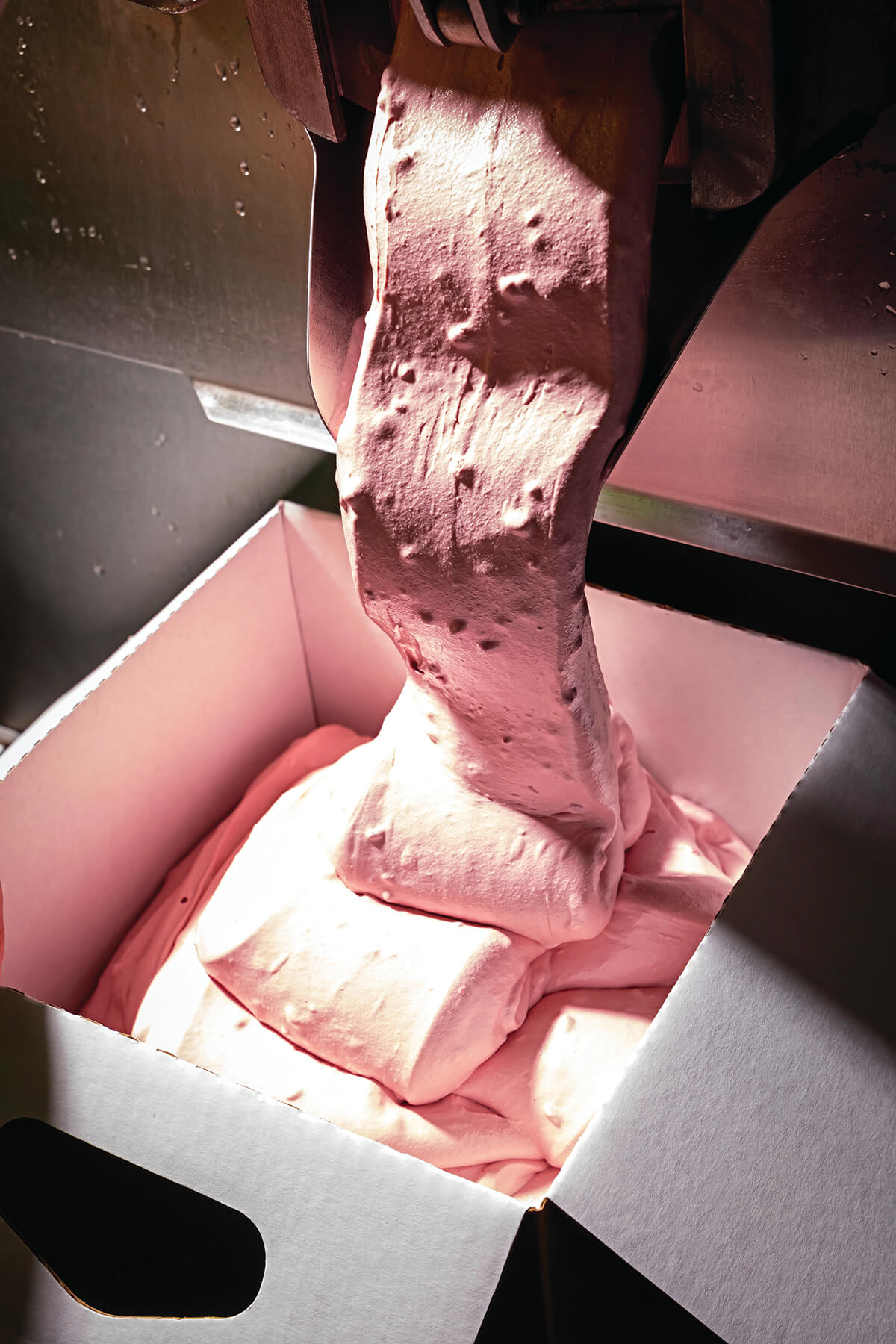

Emmy and her father also bottle gallons of ice-cream mix, which will be used to make different ice-cream flavors to sell at the farm store and local places like Brad’s Farm Market in Churchville and the 32nd Street Farmers Market in Waverly.

“Vanilla is the most popular,” says Darcy Musni, the in-house ice-cream maker. He is working in a small space off the store kitchen, replenishing the well-liked flavor after it sold out over the weekend. On this day, he’s also making vanilla cinnamon honey, orange cream, Irish cream, caramel cashew, and butter pecan. A blackboard alerts customers to the available choices of the day.

Kate Dallam spends most of her days at the store, overseeing the operation. She starts her days early, too, delivering products to coffee shops and farm markets and picking up fresh fruits and vegetables for menu items, including her “famous salad,” a healthful mix of in-season produce. She often finishes up in the evening by making more deliveries or going to the plant, where she cuts giant blocks of cheeses into consumer-size chunks.

“It’s hard to get a younger generation interested in farming.”

During an afternoon lull, Kate talks about the future. She doesn’t plan to retire, but she’d like to scale back. “The food is something I have to do every day,” she says. “I’ve created a monster. But people love the food.”

Judith Williams-Rice, who lives in Abingdon, has been coming to the store for 20 years. Now that she’s retired, she makes the trip at least twice a week. “I think I’ve had everything on the menu,” Williams-Rice “The food is wonderful.”

The community support makes the effort worthwhile to Kate, who knows that some customers travel long distances to get to the farm. “People have to drive here, so I wanted to create café offerings that would set us apart,” she says.

While she hasn’t milked cows for a long time, she’s no stranger to dairy life. She grew up milking cows at her family’s Woolsey Farm in Churchville. It’s where she met her husband, who was milking cows for her father.

“It’s like a country-music song,” she says.

Her father, Gene Umbarger, 91, can often be found at the Bel Air Farmers’ Market, where Emmy and Belle sell their wares on Saturdays. He’s so proud of his granddaughters, he says. Finally, on Sundays, Emmy takes a day off. Belle takes off another day during the week, so at least one of them is at Broom’s Bloom every day.

“It’s a 365-day-a-year deal,” Kate says. “It’s a lot.”

But she and David are “thrilled” their daughters are continuing the family legacy.

“It’s hard to get a younger generation interested in farming, and especially dairy farming,” Kate says. “You don’t want to be the last

generation to farm.”

Commander in Cheese

Each week, Nan Peppmuller makes about 40 pounds of cow’s milk cheese in the Broom’s Bloom Dairy processing plant over the course of two days. Her repertoire includes various cheddars, Gouda, feta, mozzarella, and her latest endeavor, Camembert.

“It’s my little baby,” she says, describing the cheese as a “fancy brie.” “But it’s very tedious.”

On a recent morning, she adds cultures to 400 pounds of milk from the dairy cows in a small vat to start the process. After a bit of waiting, she puts on galoshes, because the next part is messy, and stirs in rennet, which coagulates the milk. Then, she scoops the gloppy mixture into “hoops,” or molds with holes, where the whey separates from the curds through the small openings. That part takes about an hour and a half before she turns the hoops over. Then she lets them dry out overnight, flips them, and puts them into aging boxes for two weeks in a refrigerated space.

Peppmuller, 33, a cousin of Kate Dallam’s, who owns the dairy farm with her husband, David, is an unwitting cheesemaker who has learned on the job. With the exception of a few years, Peppmuller has worked at the dairy store since she was a 15-year-old student at Aberdeen High School, scooping ice cream. Dallam promoted her to cheese-making duties about a year and a half ago.

“I’m really enjoying it and hope it lasts,” says Peppmuller.

Dallam’s daughter Emmy and a niece, Ariel Taxdal, both of whom took a cheesemaking course at Penn State, gave Peppmuller tutorials in the artisan craft. She also visited the plant of an Amish farmer who previously made the farm’s cheese.

“I learned by doing,” she says.

The cheeses she makes are sold at the store and at farmers’ markets and are also used in menu items at the café.

“I love using our products in what we serve here,” says Dallam, who runs the store. “We milk the cows. We make the cheese, and I make macaroni and cheese out of that.”

Peppmuller also turns out a variety of cheese curds, which she describes as younger cheddar. The peanut-sized chunks don’t have to be aged. Whatever the task, after so many years at Broom’s Blooms, Peppmuller is incredibly content.

“I love cheese. I love it all.”