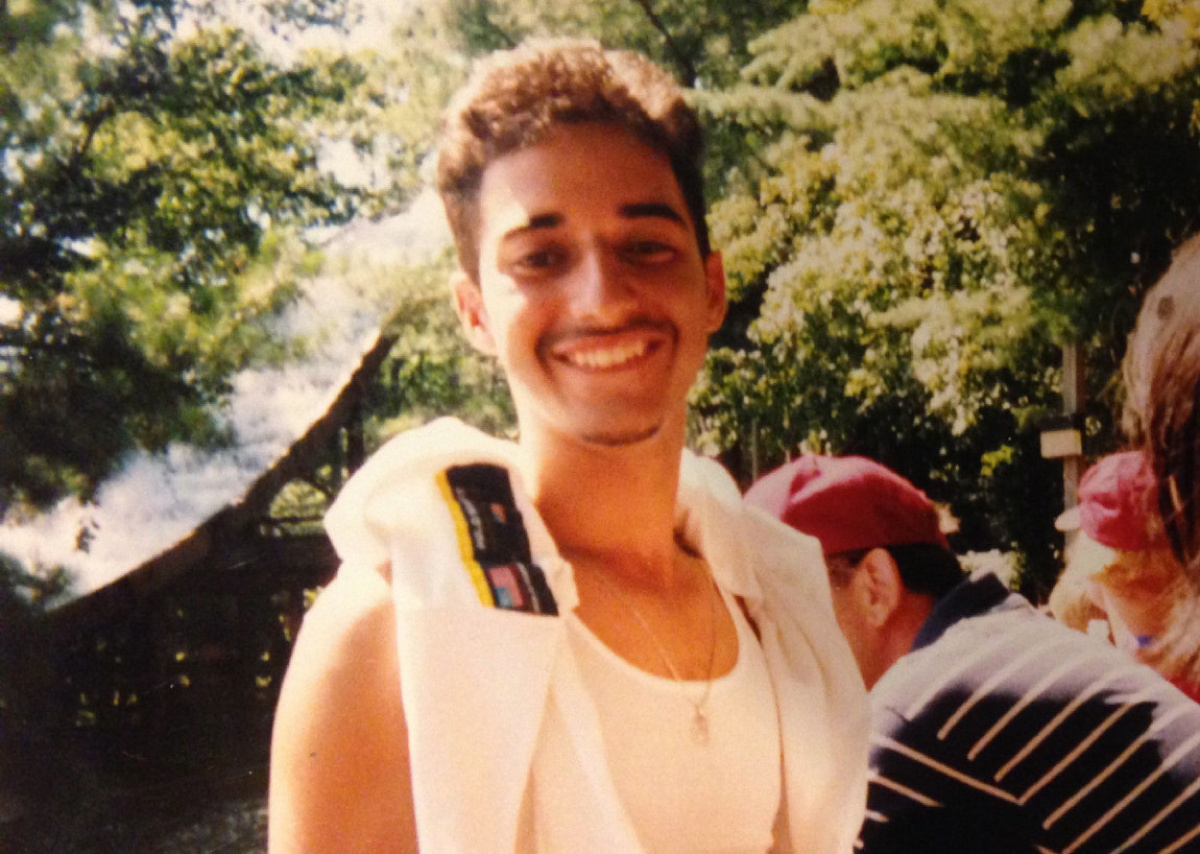

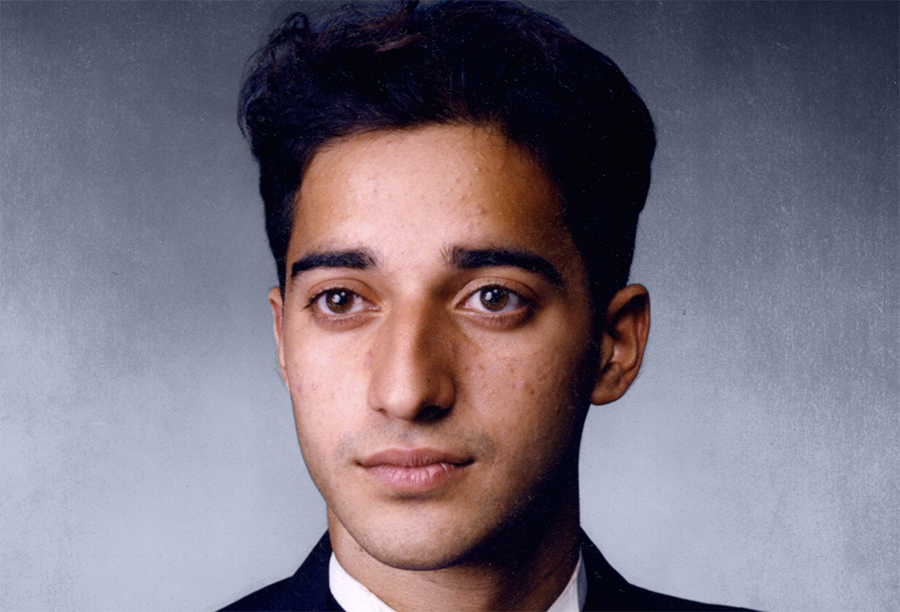

Convicted of killing his former girlfriend in 1999 when he was 17 years old, Baltimore County native Adnan Syed was sentenced to life in prison plus 30 years. The controversial case—which largely rested on the testimony of an acquaintance of Syed’s who claimed to have helped him bury the body of Woodlawn High School classmate Hae Min Lee in Leakin Park—became the first subject of the pioneering true crime podcast, Serial.

On Monday afternoon, after 23 years in prison and eight years after the podcast brought the case national attention, Judge Melissa M. Phinn of Baltimore City Circuit Court vacated the conviction “in the interests of justice and fairness.”

In a remarkable turn of events, after years of appeals by Syed’s defense team, it was prosecutors who requested the decision be overturned because, “the state no longer has confidence in the integrity of the conviction.” Phinn found that prosecutors had initially brought forth unreliable evidence in Syed’s trial and failed to turn potentially exculpatory evidence over to his defense attorney, which includes newly found evidence in his file that could have impacted the jury’s decision.

History & Politics

Archives: The Case Against Adnan Syed

Refresh your knowledge of the case with all of our detailed coverage dating back to 2014.

A recent year-long investigation conducted by Assistant Public Defender Erica Suter—Syed’s attorney and director of the University of Baltimore School of Law’s Innocence Project Clinic—in cooperation with Becky Feldman—chief of the Sentencing Review Unit of the City State’s Attorney’s Office—revealed that investigators knew of at least one, and possibly two, alternative suspects before Syed’s trial, but failed to disclose that information.

A prosecutor’s handwritten notes, apparently never shared with or seen by the defense, about one of the suspects was recently discovered in Syed’s case file. Withholding potentially exculpatory evidence by prosecutors is commonly known as a Brady violation. (Brady v. Maryland refers to a case around a 1958 botched robbery-turned-murder in Southern Maryland.)

“Mr. Syed’s conviction rests on the evolving narrative of an incentivized, cooperating, 19-year-old co-defendant, propped up by inaccurate and misleading cell phone location data,” Suter wrote in a court motion, referring to Jay Wilds, Syed’s former acquaintance whose testimony prosecutors no longer find credible. “This was so in 1999…It remains so today.”

Suter originally brought the case to the Sentencing Review Unit following last year’s passage of Juvenile Restoration Act, which enables individuals convicted of crimes as juveniles to request a sentence modification after serving at least 20 years of their prison sentence. Syed’s defense also argued that an alibi witness who’d said she saw the senior in the school’s library at the time of the murder had been ignored. Additionally, they argued that police and prosecutors claimed to have tracked his cell phone to chronicle his movements on the day of Lee’s murder—even as his carrier, AT&T, said that the data was unreliable.

The Undisclosed podcast—in which lawyers Colin Miller, Susan Simpson, and Rabia Chaudry (a family friend of Syed’s who has remained an advocate for his release since the beginning) investigate wrongful convictions—also took a deep dive into Syed’s case in its first season. Serial host Sarah Koenig, who was at the courthouse when Syed was released Monday afternoon, dropped a new 13th episode updating listeners on Tuesday.

In the wake of the news, Maryland Attorney General Brian Frosh released a statement that said the allegations prosecutors intentionally kept evidence from Syed’s defense are not true. So it remains an open question as to why it took so long for the information to come out. Frosh added that City State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby, who has not previously addressed the case publicly, did not consult with prosecutors in the case, nor with anyone in his office, regarding the alleged violations.

“Among the other serious problems with the motion to vacate, the allegations related to Brady violations are incorrect,” Frosh said in a statement. “Neither State’s Attorney Mosby nor anyone from her office bothered to consult with either the assistant state’s attorney who prosecuted the case or with anyone in my office regarding these alleged violations. The file in this case was made available on several occasions to the defense.”

Coincidentally, Thiru Vignarajah, who ran for City State’s Attorney in 2018 and 2022, and for mayor in 2020, served as the lead attorney for the State of Maryland in the post-conviction appeals of Syed. Ivan Bates, who also ran against Mosby in both 2018 and 2022, and defeated both her and Vignarajah this year, said back in 2018 that he would move to drop the charges against Syed and reopen the case.

For now, Syed remains free and appears unlikely to face a new trial—although it has not been ruled out by prosecutors.

Phinn gave prosecutors 30 days to decide to file for a new trial or drop the case. Currently, they are awaiting results from new DNA analysis ordered earlier this year. In the meantime, the 41-year-old has been ordered to wear a GPS monitor and serve home detention pending a new trial.

“To be clear, the State is not asserting, at this time, that Mr. Syed is innocent,” the Baltimore City State’s Attorney Office said in a statement. “While the investigation remains ongoing, when considering the totality of the circumstances, the State lacks confidence in the integrity of the conviction and requested that Mr. Syed be afforded a new trial.”

Lee’s family attorney Steve Kelly said he feels “betrayed” by the Baltimore City State’s Office after being assured for more than two decades that they’d made a just conviction in the case. He said they are considering their options, which may include an appeal. “What happened [Monday] was that they were completely blindsided by this process,” Kelly said.

In the meantime, prosecutors said that along with Baltimore police they will continue to investigate the alternative suspects, who have not been identified because authorities maintain it could compromise their investigation.