History & Politics

Baltimore is the second most corrupt federal jurisdiction in the country. Can a city with our history be reformed?

By Ron Cassie

Illustration by Ryan Olbrysh

Opening spread: From left, Cheryl Glenn/AP Images, Jacqueline McLean / The Baltimore Sun, Mary Pat and Thomas Bromwell Sr. / Getty Images, Sheila Dixon and Catherine Pugh / Courtesy Of Maryland State Archives; Marvin Mandel and Spiro Agnew /AP Images; Nathanial Oaks / Courtesy Of Rachel Baye, WYPR; Shutterstock

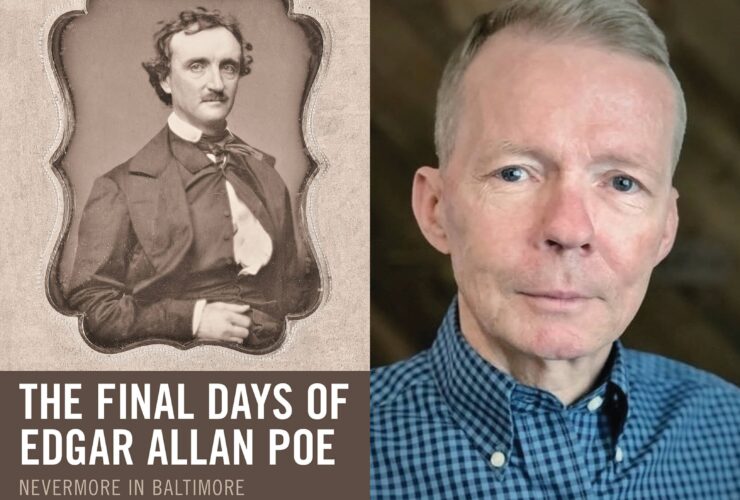

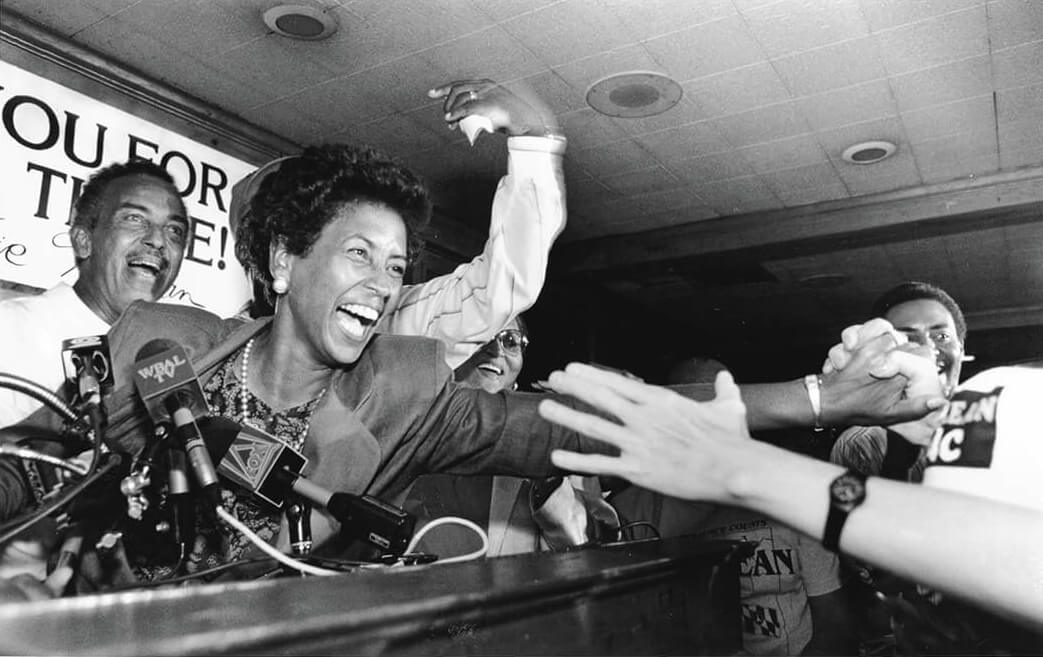

1991, THE CITIZENS OF BALTIMORE elected 47-year-old Jacqueline McLean their new comptroller, the first woman ever to hold the city’s third most powerful position. After eight years on the City Council, McLean swept into office in high style, cruising to a resounding win for the open seat following the retirement of colorful, “champion of the little guy” Hyman Pressman, who had served seven terms and 28 years before announcing his retirement. The fashionable co-owner (with her husband) of an apparently successful travel agency, Four Seas & Sevens Winds, Inc., McLean presented as every bit the savvy businesswoman with a large house in Guilford, two vacation homes, and assets valued at more than $1.7 million. Political observers, including her fellow elected officials, felt certain she’d make a strong run for mayor someday. It had been a remarkable ascent. The sky was the limit.

“With Jackie’s smashing victory, it potentially sets her up for bigger and better things in the city,” state Sen. Nathan Irby said after McLean’s big win in the Democratic primary, adding, “. . . she knows how to play. That’s the key to politics.”

McLean had not risen from the east or westside Democratic clubs when she launched her political career in 1983, bypassing the establishment by spending gobs of her own cash on her campaign and TV ads. Her wealth had not only made her candidacy possible, but seemed its very basis. She trumpeted her business acumen and captured the public’s imagination with its symbols of success—beautiful homes, smartly tailored clothes, and stylish jewelry. When asked after her first political victory about the seemliness of using her own money, lots of it, to buy herself a seat on the City Council, she’d smiled sweetly, the Baltimore Sun reported, and said, “He who has the gold makes the rules.”

Jacqueline McLean, winning the comptroller race, 1991. THE SUN

Despite budget troubles, Baltimore’s new fiscal watchdog hosted an $85-a-ticket black-tie affair at the Sheraton Inner Harbor, a see-and-be-seen occasion billed as the First Comptroller’s Inaugural Ball. (Buttoned-down Mayor Kurt Schmoke, citing city layoffs, skipped the gala and went back to work following the afternoon swearing-in.) Earlier that day, McLean had put a brand-new $19,789 Mercury Grand Marquis with a telephone, tape deck, and air conditioning on the taxpayer’s tab, telling reporters she needed the vehicle because she didn’t own car. The MVA later indicated otherwise, noting their records had her registered as the co-owner of three vehicles actually, a BMW and a pair of Cadillac sedans.

Things spiraled downhill from there. The early ’90s recession that helped Bill Clinton win the presidency had taken a chunk out of McLean’s travel empire. She struggled, selling off parts of her business, and then became desperate to maintain appearances and the lifestyle to which she had become accustomed. In late 1993, she took indefinite leave amid a state investigation of financial improprieties, which included steering a $1-million city lease to a building she owned and more than $23,000 in payroll to a fictitious city employee named Michele McCloud. The ethereal Ms. McCloud’s address happened to be the same as the comptroller’s sister’s hair salon.

One of the attorneys the state prosecutor tapped for the McLean investigation—the beleaguered comptroller eventually resigned and was convicted of misconduct in office—was a $6-an-hour former bank fraud investigator who had just graduated night law school at the University of Baltimore. “My first big case,” says Isabel Mercedes Cumming, pointing to the courtroom sketch from the McLean trial that hangs behind her desk in the sixth-floor City Hall Office of the Inspector General, which she now leads. “In my experience,” Cumming says, “people who commit corruption, fraud, and accept bribes are sometimes facing a financial setback, but mostly they are people who simply want more. In the juvenile courts, you hear stories of tragic lives. That’s not the case with financial crimes. They’re concerned with keeping up with the Joneses. The Jacqueline McLean case and trial should have been a cautionary tale.” As Baltimoreans know by now, that’s not how things go here. Sheila Dixon, the future disgraced mayor, was one of several councilmembers who attempted to intervene on McLean’s behalf with the judge in the case.

Years after the McLean case, which had divided and thrown City Hall into turmoil (not unlike today with the ongoing FBI investigation of City Council President Nick Mosby and his wife, City State's Attorney Marilyn Mosby), Cumming headed up anti-fraud, waste, and corruption offices in Prince George’s County and Washington, D.C. In 2006, she was named international fraud investigator of the year and, at the recommendation of then-City Solicitor Andre Davis, Mayor Catherine Pugh hired Cumming back to Baltimore to fill the city’s Inspector General post, which had been vacant for 16 months, at the start of 2018. Tellingly, half of the office’s 10 funded positions were also vacant and just four reports had been issued the year before Cumming took over. “I love Baltimore and had applied the last time the position was open,” says Cumming, who graduated from Loch Raven High School and whose city roots run deep. “For me, it was a full-circle moment.” And perhaps more than she bargained for.

“What I remember from interviewing with Mayor Pugh was how happy she was. She told me she’d just closed on a new house that day and it was down the street from where she lived, in Ashburton,” recalls Cumming, who later assisted with the campaign finance and Healthy Holly investigation that brought down the former mayor. She pauses as the now-surreal memory sinks in. She’d soon come to learn that Pugh had used proceeds from the bogus sales of her discredited children’s book to buy her new home. Not to mention, fund her campaign and help swing the election. “She kept saying it was her ‘dream house.’ She was just so happy.”

Isabel Mercedes Cumming, head of Baltimore City's office of the inspector general, which has identified more than $6 million in savings due to waste, inefficiency, and fraud since she took over in 2018. Photography by Schaun Champion

“The Jacqueline McLean case and trial should have been a cautionary tale.”

f, as the saying goes, once an accident, twice a coincidence, three times a pattern, then corruption, waste, and fraud is not just pattern at City Hall, but practice. The same obviously goes for the city’s police department, which had one of the highest rates of officers who were arrested before the crimes of the Gun Trace Task Force came to light. Former police commissioners Darryl DeSousa and Ed Norris were sent to jail for tax fraud, and also in Norris’ case, misusing police money to fund extra- marital affairs. A third commissioner was fired following allegations of domestic violence. Overshadowed today, a federal investigation of a towing kickback scheme uncovered in 2011 involved more than 60 officers, leading to 16 convictions inside the department.

Similarly, in terms of city politics, corruption has hardly been limited to the high-profile implosions of McLean, Dixon, and Pugh. If only it were so. Former Baltimore state Senator Nathaniel Oaks was convicted of bribery three years ago after a previous theft conviction in the late 1980s while serving in the General Assembly. Former City state Delegate Cheryl Glenn pleaded guilty last year to accepting more than $33,000 in bribes related to bills involving the cannabis industry. Pugh aide Gary Brown, who created $62,000 in false invoices from “sales” of her Healthy Holly children’s book—which went directly to her or were funneled to Pugh’s campaign through straw donors—was convicted after he’d been awarded with a state delegate appointment. Then, of course, in March, came the double-whammy news that the FBI was again at City Hall, this time delivering a subpoena to Council President Nick Mosby, who is the subject of a federal investigation with his wife, City State’s Attorney Marilyn Mosby. The grand jury inquiry appears to involve her campaign finances, their business interests, and federal tax returns. Previously, it was reported a $45,000 lien had been placed against the Mosby’s home because of unpaid taxes, which Nick Mosby at various times has confirmed, denied, said was paid off, and said was in the process of being paid off, but never fully explained. Meanwhile, Marilyn Mosby, who managed to get approved for mortgages on two Florida homes while the lien against the couple’s home was by all indications still in place, has attacked Cumming, who Mosby had asked to investigate her in an effort to clear her name, and the media. The very nature of a married couple holding two citywide elected offices presented several conflicts of interest from the outset—the Council oversees the State’s Attorney’s Office and the Inspector General’s budgets, for example—and it took just a few months after Nick Mosby’s election for it to blow up. “Disheartening,” a Democratic party insider called the revelation of the FBI investigation. “Another body blow for the city.”

“Disheartening,” A Democratic Party Insider Said Of The FBI Investigation Of The Mosbys.

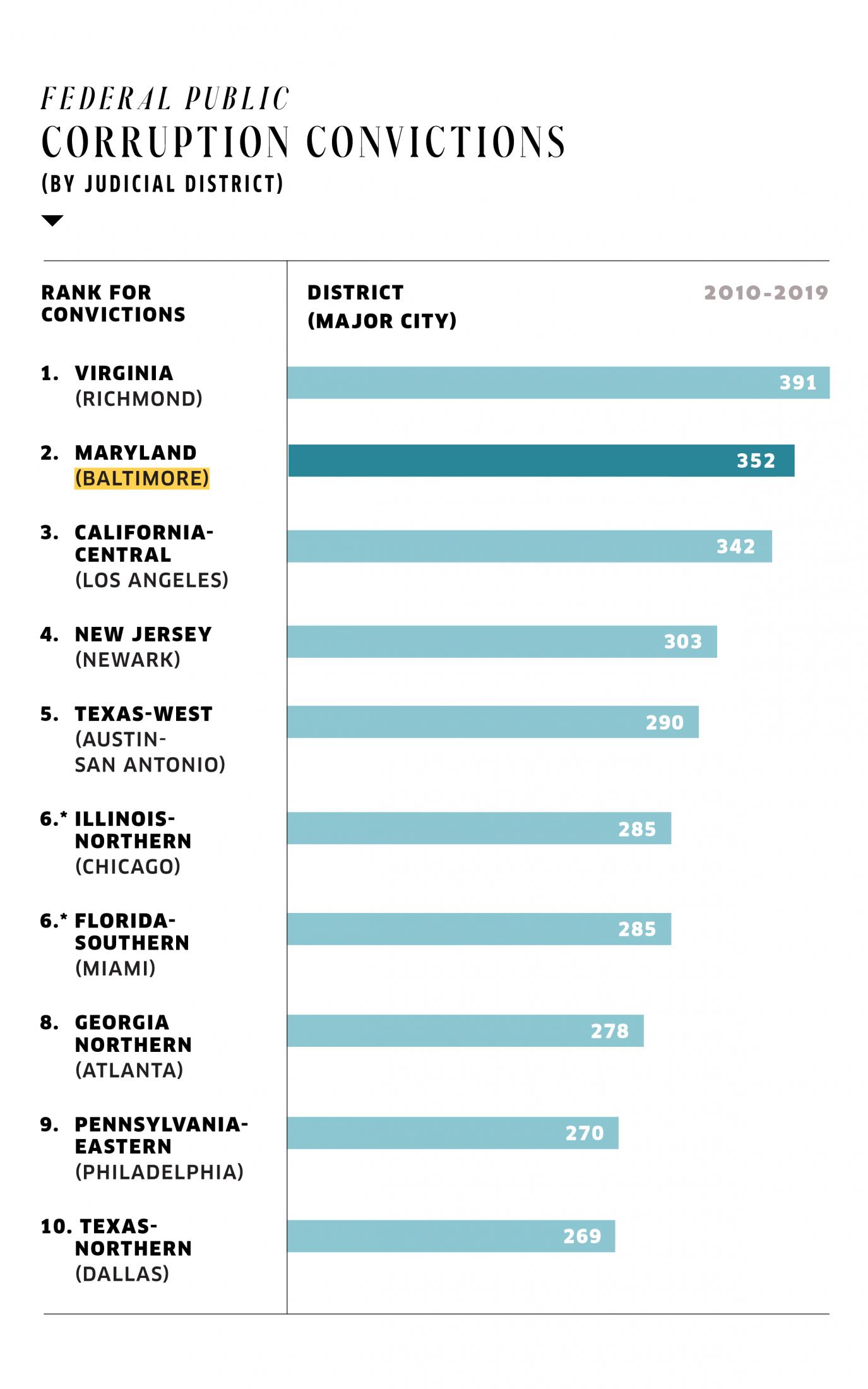

So how does Baltimore stand up against other jurisdictions? Is corruption the same everywhere? It’s difficult to tally every local, state, and federal corruption conviction city by city, but the short answer is no. According to a new University of Illinois at Chicago study of just federal public corruption convictions by judicial district, Baltimore has become the second most corrupt jurisdiction in the country—with a staggering 352 guilty pleas or verdicts over the past decade. In many of the most notorious jurisdictions, corruption convictions had actually fallen in recent decades. As it is in so many metrics, Baltimore is an outlier. To be fair, our federal jurisdiction far exceeds the city’s geographic boundaries, including the Metro region, Eastern Shore, and Western Maryland, but that’s true elsewhere, too. With that caveat, the Baltimore federal jurisdiction area led the U.S. in corruption convictions by a sizable margin in 2018, the next to last year of the report, much of it tied not just to political wrongdoing, but scandals involving Baltimore police and prison guards from the state department of corrections.

“Motive—money, staying in power, more money— those things are universal. But what corruption looks like at every level of government is different,” says former Chicago alderman and University of Illinois at Chicago political science professor Dick Simpson, one of the co-authors of the school’s annual anti-corruption report. “At the executive level, a governor or a mayor, it might involve appointments to certain positions, like a pension board, or the awarding of contracts, which can translate to kickbacks, like a $25,000 campaign contribution. In the state legislature, it’s pushing certain legislation. At the city council level, it be might be zoning help in exchange for campaign contributions, but rarely a direct bribe.”

Simpson, who has studied corruption for a half-century, shoots down the idea that investigators are simply better or more aggressive today at catching politicians or police officers with their hand in the proverbial cookie jar. “Corruption comes first,” he says. “Then, maybe you find it. Even the number of convictions, 352 in Baltimore? That’s misleading. We estimate, and it’s not based on data, just our feeling from the research we do, that for every person who is convicted of corruption, there are 10 more who were complicit in one way or another, but not prosecuted. Where does that put the real number of people involved in corruption in Baltimore?”

Case in point: None of the University of Maryland Medical System board members who authorized the fake Healthy Holly purchases faced any charges. Neither did J.P. Grant, a businessman with millions of dollars of contracts with the city who cut a $100,000 check to Pugh.

The University Of Illinois At Chicago’s Corruption Report is compiled using annual statistics from The U.S. Department Of Justice (DOJ) Criminal Division’s Public Integrity Section.

Meanwhile, more shoes are certain to drop inside City Hall.

Office of the Inspector General

Years in Review

Source: Baltimore City Office of the Inspector General

n truth, much of the unlawful and unethical activity in and around City Hall—overwhelming in volume for years—has been obscured by the drama of mayoral indictments. Consider in just the three years since the Office of the Inspector General became independent of the mayor’s office, more than 20 city employees have been criminally charged or forced to resign for ethical wrongdoing of one kind or another. They include the heads of the Department of Transportation (DOT) and the Department of Human Resources, the chief of Fleet Management, and the director of the city retirement system. Last year, a Department of Public Works supervisor pleaded guilty to extortion after federal prosecutors charged him with accepting cash payments for work he had DPW crews perform for private businesses. In 2018, a longtime DOT supervisor pleaded guilty in federal court to taking thousands in bribes in exchange for construction permits. In 2017, the third director of the Mayor’s Office of Information Technology was forced out for alleged misconduct, poor management, and unethical behavior. With a decade of chaos atop the Office of Information Technology, it does not come as a surprise the city was hit with a pair of ransomware attacks in 2018 and 2019. The second attack caused officials to power down the majority of city servers and ground City Hall to a standstill. Who can forget the image of a handwritten note on the door of the Department of Public Works water department office: “Systems are down until further notice. Thank You!” The hack cost Baltimore taxpayers at least $18 million to remediate, with $6 million transferred from a fund for parks and public facilities.

Going back a bit further, to 2015, the former chief of the Division of Transit and Marine Services was sentenced to a year in prison after taking a $20,000 bribe to cancel a $60,000 debt owed to the city, and a $70,000 bribe to allow the theft of city property worth $250,000.

Mayor Brandon Scott at Mergenthaler Vocational Technical High School, His Alma Mater. The Former City Council President Edged ex-Mayor Sheila Dixon by 2.1 percent points in last year's Democratic primary. Photography by Schaun Champion

eanwhile, more shoes are certain to drop inside City Hall. Currently, there are 35 investigations underway and 48 pending probes that Baltimore’s Office of the Inspector General has in the works. Just following the recent completion of seven as of yet unpublicized IG investigations, Cumming said more terminations and/or criminal investigations are likely to result. The IG’s office does not initiate investigations on its own—nearly all begin with whistleblower tips, which flood the office’s inbox on a daily basis. Typically, they are generated by a citizen, vendor, or city employee, and less often a city official. Nor does it request penalties or criminal charges, merely moving its reports to the relevant city officials and department heads, or working with law enforcement agencies if necessary, who make those calls. Cumming has gone to lengths to promote the hotline, attending outreach events and media interviews to get the word out about her office’s work, which focuses on waste and inefficiency, as well as corruption and fraud. Tips have quadrupled during her tenure, rising to more than 750 last year, and are on the same pace in 2021. Last year, the Office of the Inspector General identified nearly $3 million in savings or waste.

Hotline tips generally come from two types of people. Sometimes, they are generated from “good government” types. Just as often, they come from someone jealous or resentful. They see a colleague in a city position driving a new car, buying new clothes, or taking trips—the lifestyle of someone they don’t like has changed—and they know it’s because they’re stealing, Cumming says. “Or it’s about someone they work with receiving better treatment because they’re sleeping with the boss and they think it’s unfair. Some people do, but not everyone reaches out because they’re worried about the city budget.”

Cumming started her career as an accountant, but quickly moved into fraud investigation. “Putting together accounting financials was godawful, but I had a knack for following the money.” To that end, the personal interests or politics of a tip don’t make a difference to Cumming, she says, only the facts of the matter, adding that the majority of hotline emails don’t actually lead to an investigation. Cumming is nothing if not diligent; her office’s annual report was completed and published in both English and Spanish three months after the end of the fiscal year. The daughter of a Puerto Rican immigrant mother and Canadian father, she is also frugal by nature—often walking or taking the bus to law school at UB, and utilizing public transit for her work commute over much her career. A former high school gymnast, she is also disciplined and fearless, a good combination for an inspector general—and traits she’s passed on to her two sons, one of whom is a professional skateboarder and the other, an Air Force pilot. (Several of her younger son’s skateboards hang in her office.) Believing that her office can’t be effective if it doesn’t represent the city’s demographics, Cumming has more than doubled the diversity of the staff since taking over. It now includes seven women, with 12 of the 17 staffers people of color. Her two top deputies, who generally write the final reports with Cumming, are both Black women.

In her highest-profile investigation to date, Cumming’s office found that City State’s Attorney Mosby sought a $5,000 tax deduction related to business losses from a travel company she’d formed, but one that she hadn’t disclosed initially on ethics forms and previously said was “inactive.” Additionally, the IG report revealed that Marilyn Mosby spent 144 days away from Baltimore in 2018 and 2019 while flying to criminal justice conferences around the country and even the world. It also did not find documentation that Mosby had donated the 41 gifts she had declared on her ethics forms in 2018 and 2019. Mosby had actually requested the IG investigation following issues raised by the Baltimore Brew, which also included other campaign reporting problems. Ultimately, she pushed back hard against the office’s findings. She hired private attorneys—apparently using money from her campaign funds, which isn’t allowed— who fired off a letter demanding Cumming change her report. When Cumming didn’t bend, Mosby’s team attempted a press conference at City Hall to ratchet up the pressure further. That effort was disrupted by an “only in Baltimore” protest by strip club dancers who were seeking to get the bars where they work, shuttered by restrictions, back open for business.

Cumming won’t comment on the DOJ investigation into the Mosbys other than to note Marilyn Mosby was the first public official in her career to request an investigation of herself. “I don’t think anyone will ever do it again,” Cumming volunteered.

o be clear, corruption is hardly out of character, historically, in the city or state. Quite the contrary. In a remarkable stretch from 1971-1979, some two-dozen City and Maryland elected officials were convicted on bribery, embezzlement, and tax fraud charges. They included back-to-back governors Spiro Agnew and Marvin Mandel, both originally from Baltimore; U.S. Senator Daniel Brewster, who accepted illegal gratuities from a Washington lobbyist; and Congressman William O. Mills, who committed suicide in 1973 at his Easton home five days after it was revealed he had received a $25,000 gift from President Richard Nixon’s re-election campaign. Baltimore County State’s Attorney Sam Green, whose bribery trial was filled with lurid tales of his sexual escapades, was also convicted in 1973. That same year, 22 City police officers were charged in connection with a bribery and gambling inquiry.

In a revealing picture of the era, former Baltimore City Councilman Allen Spector, a longtime ally of Mandel, told the Washington Post that the governor hadn’t done anything wrong in accepting $350,000 in gifts, trips, and made-up legal fees from four businessmen buddies. “It’s like they changed the rules in the middle of the ball game,” Spector said, repeating a familiar refrain of politicians at the time. “In politics,” he added, “we were all raised with the idea that the guys who helped you, you favored.” Convicted of paying bribes in 1974 and 1975, Spector was nonetheless soon appointed to a judgeship on the Baltimore City District Court, where he was convicted of accepting bribes in 1980. (His wife, Rikki Spector, was appointed to fill his City Council seat in 1977 when he was selected for the bench and remained there for four decades.)

The political corruption convictions never stopped in Baltimore or, more broadly, Maryland. In 1988, Baltimore state Senator Michael Mitchell and his brother, former Baltimore state Senator Clarence Mitchell III, were each sentenced to two and a half years at a prison camp in Pennsylvania for taking payoffs to block a federal investigation. The same year, Michael Mitchell was also convicted of stealing $77,417 in life insurance benefits intended for the 3-year-old child of a murder victim. Two of the biggest convictions actually involved big-dollar lobbyists: Bruce Bereano was convicted in 1994 of billing his clients for entertaining lawmakers and using the money to make illegal contributions. A few years later, Gerard Evans was convicted of defrauding his clients of more than $400,000. In 1998, powerful former Baltimore state senator Larry Young was expelled from Annapolis' upper chamber after a report from the Joint Committee on Legislative Ethics concluded he had leveraged his political position to enrich himself. (Interestingly, Young, said to have partially inspired the character of Clay Davis in The Wire, former police commissioner Ed Norris, and former state Senator Clarence Mitchell IV—known as C4 and formally reprimanded by the General Assembly for failing to report a $10,000 loan from a Baltimore bail bondsman—all became and remain popular talk radio hosts in the city.) For the most part, however, the corruption convictions did slow down in the post-Watergate period—until recently.

In 2007, former Baltimore County state Senator Thomas Bromwell was sentenced to seven years in federal prison for taking bribes from a construction company. His wife, Mary Pat Bromwell, was sentenced to a year in prison for accepting payments for a no-show job. In 2013, former Anne Arundel County Executive John Leopold was sent to jail after being convicted of multiple counts of misconduct in office. His offenses including using his county-provided police security to investigate political opponents, remove campaign signs, and drive the 69-year-old elected official to places where he could have sex with female liaisons. In 2017, Gov. Martin O’Malley’s former secretary of information technology was indicted on four counts related to bribery, a case that is still playing out in federal court.

Last November, Former Councilman Bill Henry Upset Joan Pratt, Who Had Been The City’s Comptroller Since Succeeding Jacqueline Mclean In 1995. Photography by Schaun Champion

he irony of the Catherine Pugh Healthy Holly saga is that her biggest selling point to many voters was that she was cast as the experienced and honest alternative to Dixon. In fact, it’s plausible her illegal fundraising scheme altered the outcome of an election that Sheila Dixon appeared poised to win. Pugh benefitted as well from a separate, unlawful $100,000 campaign loan from a political slate funded by Jim Smith, a former judge and Baltimore County Executive whom she later hired as a top aide. As early voting started, news outlets reported Pugh’s campaign offered $100 and chicken boxes to work for the campaign. When residents turned up for the jobs, however, they were told they first needed to get on a bus to a voting site and cast their ballot. Pugh’s crimes would dwarf those of Dixon, but it’s worth remembering, Dixon had been in ethical controveries since her days as City Council president, voting on contracts that involved her campaign manager and providing her sister a paying position in her City Hall office.

The silver lining in Pugh’s election—and there really is one—is that her disastrous tenure sparked a number of reforms that will add accountability to City Hall and democratize the balance of power in going forward.

First and foremost, the 2018 referendum authored by City Councilman Ryan Dorsey that moved the Office of the Inspector General out from beneath the mayor’s office has already become a game changer. In 2020, the City Council also voted to move the Ethics Board—previously almost nonexistent—under the Office of the Inspector General, which has assigned staff to assist the Board. It's the first time in city history the Ethics Board has enjoyed full-time staff. “There are roughly 3,000 city employees required to fill out ethics forms,” Cumming says. “Last year, about 600 didn't submit an ethics form at all. Another 1,000 had to be sent back because they had been filled out incorrectly.”

Then, in direct response to Pugh’s Healthy Holly case—but certainly with Dixon’s scandal in mind as well—Baltimore voters approved a charter amendment last fall that formalizes the process for removing elected officials. The law does not require a criminal conviction, but allows the City Council with a three-fourths vote to remove a councilmember, the council president, mayor, or comptroller for “incompetency, misconduct in office, or willful neglect of duty.” Almost immediately after the FBI inquiry became public, speculation began in and around City Hall about who might replace Nick Mosby as council president. The charter amendment does not cover the position of the city state’s attorney, whose removal for wrongdoing is covered by the state charter.

Another amendment significantly increased council input and oversight over the city budget. Previously, Baltimore’s charter gave the mayor almost complete control of spending in the process, with the council only able to identify cuts. Now, the council can reallocate money it cuts from the budget to other departments or programs.

Two other referendums made it easier for the council to override mayoral vetoes. The first reduced the number of votes the council needs to override a veto, and the other closed a timeline loophole that previously allowed mayors to skirt veto votes altogether, which is essentially what allowed Pugh to renege on a campaign pledge to support a city $15 minimum wage. “Democracy and accountability are not just related, they’re really the same thing to me,” Dorsey says. He adds he’d like to make the city council president job an appointed position by councilmembers—the way it’s done in the U.S. House and Senate and both chambers of the General Assembly. As an elected position, paradoxically, he notes, it reduces genuine democracy by curtailing the power of each of the other 14 councilmembers.

Finally, voters in November approved a city administrator position to work alongside the mayor and oversee the day-to-day operations of city government.

Scott made increased transparency and accountability at City Hall a campaign promise. Photography by Schaun Champion

Things at City Hall aren’t perfect, former longterm officials admit. There remain serious issues ranging from how the city awards contracts via the Board of Estimates to the outsized influence of developers. If you’ll recall, a grand jury indicted Dixon on charges that she failed to report accepting roughly $15,000 in gifts from developers Patrick Turner and Ronald Lipscomb. “Powerful people have powerful influence without resorting to anything illegal, and that’s a problem,” says long-serving and recently retired Councilwoman Mary Pat Clarke. “Especially in the development community, things do go on that run counter to what the community would want, and those are considered under-the-table transactions.”

For all the overdue structural reforms, voters ultimately have to place trust in those they put into office. In that vein, there was more cause for optimism in November when former Councilman Bill Henry upset Comptroller Joan Pratt, who had been in office so long she had actually succeeded McLean. After decades without audits of major city agencies under Pratt, the City Council passed a measure requiring regular performance and financial audits of 13 agencies by 2016—a mandate the comptroller's office has since struggled to meet. Pratt was also involved in multiple controversies over her 25 years in office, starting with giving former boyfriend Julius Henson a $79,900-a-year job managing the city’s multi-billion-dollar real-estate holdings in 1996. (Henson later went to jail for organizing illegal campaign “robocalls” on behalf of Governor Bob Ehrlich.) In a report last year, the city Office of the Inspector General found Pratt voted 30 times to approve more than $48 million in spending that involved organizations she appeared to have had relationships with. That included a 2017 vote to approve the sale of 15 city-owned lots for $1 apiece to her church, Bethel AME. Ultimately, her association with Catherine Pugh, with whom co-owned a boutique that Pugh used to launder money, probably did in her reelection bid.

If Henry’s election was cause for cautious optimism, Mayor Brandon Scott’s dramatic come-from-behind victory over Dixon, who finished an extraordinarily close second again, was another reason to hope the city could turn a page on its scandals. Scott’s win played out over a dramatic week of mail-in ballot counting.

In his “first 100 days” address, Scott— who neither drinks nor smokes; rents a $1,110-a-month, two-bedroom apartment; and until recently still drove a 2007 Saturn— referenced Baltimore’s recent political scandals. “Just like the start of any new relationship, establishing trust is key,” he said. “This is especially true when trust has been broken over and over again.” Along those lines, in one of his first significant actions in April, Scott launched the city's new Open Checkbook initiative, fulfilling a campaign transparency promise. The online database tool, increasingly utilized in other cities, allows Baltimoreans to view day-to-day spending by city agencies and vendors.

A week after the Mosby investigation made news, Scott had gone out with members of his team and the fire department on a public safety walk just south of Mergenthaler Vocational Technical High School, better known as MERVO, and his alma mater. Specifically, Scott was gathering information, clipboard in hand, from homeowners in the largely retired, Black neighborhood about recurrent, massive flooding on the otherwise quiet block. Just crossing the street, it was apparent people here wanted to believe in the 37-year-old mayor, immediately recognizable to passersby with his stylish and bold Afro, and they greeted him with enthusiastic waves.

Afterward, Scott downplayed the challenge presented by the ongoing investigations of two of Baltimore’s four citywide elected officials. He didn’t dismiss the burden imposed by the convictions of two of his three predecessors, but wasn’t particularly interested in discussing them either, noting no one he’d met on their porch that afternoon had raised the subject. “People want to know how you’re going to help them,” Scott says. “They want answers to their questions and confidence that the city is going to perform its nuts and bolts functions. Nobody had ever been out here before, and that was part of their frustration.”

Which was true. But after the mayor had moved on, Warren “Skeeter” Williams, a 73-year-old retired city worker, and his wife, 72-year-old Pamela Williams, a retired health care worker, did express more than just frustration with DPW’s response to the flooding, which has cost them three vehicles to date and thousands of dollars in basement repairs. Scratch beneath the surface, and there is deep disappointment and frustration with City Hall. “We follow the news, and we were very upset with everything that came out with Catherine Pugh, and some of the other politicians, too,” Pamela Williams says. “We’re on fixed incomes, and if I don’t pay my taxes or I don’t pay my water bill, I know that I will lose my home. So many of them seem to think they can get away with anything. You’re the mayor of Baltimore, and you’re misusing your office? With all the problems we have? They think the rules don’t apply to them.”

RON CASSIE is a senior editor at Baltimore. Freelance writer ADAM BEDNAR contributed to this story.