History & Politics

No Small Deaths

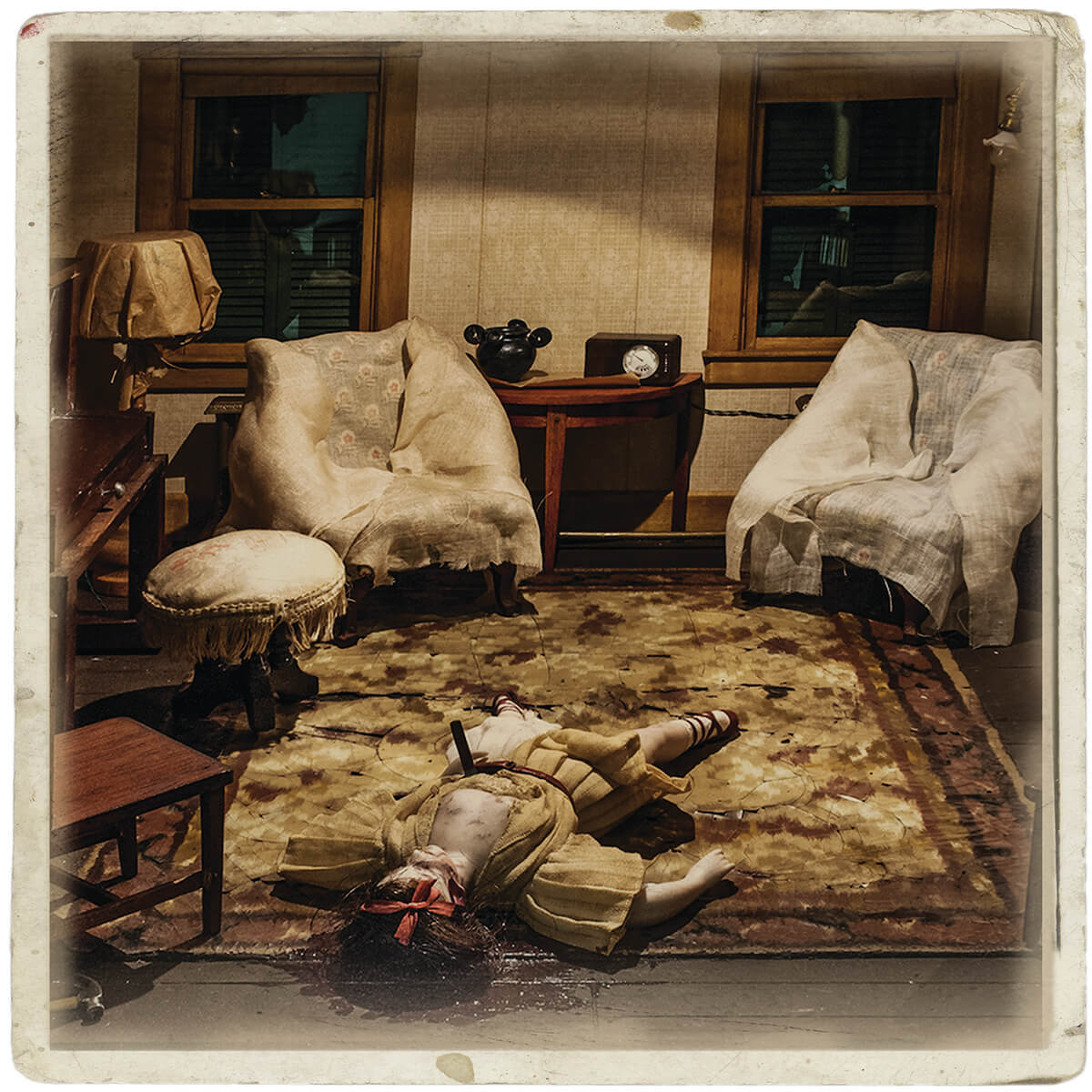

Frances Glessner Lee's famous dioramas teach detectives how to evaluate crime scenes.

In 1929, following a surgical procedure, the nature of which isn’t known, heiress Frances Glessner Lee spent a period recuperating alongside George McGrath, the local Suffolk County medical examiner, at a private wing of Massachusetts General Hospital.

By happenstance, McGrath, an old Harvard College friend of Lee’s recently deceased older brother, was receiving treatment for a severe bacterial infection afflicting his hands, a consequence of circulatory problems related to a weak liver and ongoing exposure to formaldehyde and industrial-strength disinfectants.

Despite his infirmity, McGrath regaled Lee, a 51-year-old inheritor of the International Harvester fortune, with tales from his work, which included no less than the cause célèbre murder trials of Italian-American anarchists Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti; the Great Molasses Disaster of 1919—the massive commercial explosion and subsequent 12,000-ton molasses tsunami that claimed the lives of 21 Bostonians; and the accidental, it would turn out, house fire that killed Babe Ruth’s first wife.

The coincidental convalescence would change Lee’s life—and death investigation everywhere. Through McGrath, Lee became intensely interested in early forensic science. Already an expert craftswoman, she eventually began the painstaking process of building intricate, true-to-life, dollhouse-size crime scenes to train homicide investigators.

After Lee’s death in 1966, the 18 now famous dioramas, known as “The Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death,” along with real-time witness statements, were handed over to Maryland’s chief medical examiner, who recognized their value.

Authentic down to the hand-rolled, quarter-inch cigarette butts, the purpose of the models is to help teach detectives how to observe, report, and evaluate crime scenes. (In one instance, Lee took a blowtorch to a small wooden cabin she’d faithfully built to mimic a fire set by a murderer to cover his tracks.)

From the tiny blood splatter patterns to the positions of the five-and-a-half-inch corpses, the gruesome dioramas continue to serve as a key component of the Frances Glessner Lee Homicide Investigation Seminar, which will celebrate its 75th anniversary this April in Baltimore.

The whodunit answers, however, remain a kept secret to protect the learning process. Today, they are known only to Jerry Dziecichowicz, an administrator in the medical examiner’s office, who describes Lee, a brilliant woman who married at 20 after her father forbade her from attending college, as “the patron saint of forensic science.” (Twelve of the 20 victims in Lee’s dioramas depict women murdered in various domestic scenes; make of that what you will.)

In 1943, Lee became the first female police captain in the U.S. when she began working with the New Hampshire State Police. There-after, notes Bruce Goldfarb, the spokesman for the chief examiner’s office and de facto curator of the studies, she preferred to be called Captain Lee.

To her grandchildren, however, Goldfarb adds, Lee, who often wore all black, was nicknamed “the Tarantula.”

“She was a sweet woman, though,” says Goldfarb, who penned 18 Tiny Deaths: The Untold Story of Frances Glessner Lee and the Invention of Modern Forensics, due out in hardcover next month.

“You see it in her correspondence. She was the type who would send her nephew money if he got good grades.”

The Nutshell Studies have gained such notoriety, inspired by TV shows such as CSI: Crime Scene Investigation, in recent years that a rare public display of the dioramas for three months at the Smithsonian’s Renwick Gallery attracted more than 100,000 visitors.

Occasionally, the curious stop by the medical examiner’s office as well. “A couple of years ago, two women grabbed me in the hallway and wanted to know the answer to one scene,” Goldfarb recounts. “I explained that I wasn’t allowed to say and it wasn’t really the point, which was to observe, document, and interpret the details. They didn’t pay any attention to me.

As soon as I finished, one woman turns to the other and says, ‘I think the husband did it.’”

Bruce Goldfarb will present his new book, “18 Tiny Deaths: The Untold Story of Frances Glessner Lee and the Invention of Modern Forensics,” at Med Chi, 1211 Cathedral St., Baltimore, Feb. 5 at 6:30 p.m. and at Atomic Books, 3620 Falls Road, Baltimore, Feb. 15 at 7 p.m.

More images of the Nutshell Studies of Unexplained Death can be found here.