History & Politics

Likable Larry

Improbably, Larry Hogan is the second-most-popular governor in the country. But is he good for Baltimore?

Outside West Baltimore’s Shake & Bake Family Fun Center, 15 brand new, all-terrain Department of Public Works litter vehicles line the sidewalk. Courtesy of a $500,000 Keep Maryland Beautiful grant from the state, the fleet of golf-cart size street sweepers is being unveiled this morning as the Cardinal Shehan school choir—of Good Morning America fame—kicks off what is billed as Governor Larry Hogan’s “regional cabinet meeting” inside the iconic roller rink.

“Cardinal Shehan school choir—incredible. Wow. I mean they put me in a hard spot,” a beaming Hogan exclaims after a rousing rendition of “Rise Up.” “I’m not sure how you follow anything like that choir.”

The governor has brought his top officials with him, including Pete Rahn, head of the Department of Transportation, and Ken Holt, the state’s housing secretary, but the event has the unmistakable feel of a crowd-for-hire campaign rally. Those cramming into the Shake & Bake—mostly white, largely made up of Maryland government employees in suits and dresses sporting state ID badges—break into applause and standing ovations during the governor’s remarks, while he touts administration efforts in the city. Even the majority of the police officers on hand appear to be from Annapolis.

Tellingly, before Keiffer Mitchell, the former city councilman and current senior advisor to the governor, introduced Hogan, he began his remarks by describing the black renaissance history of Pennsylvania Avenue and the story behind the roller rink, which was started decades ago by former Colt Glenn “Shake & Bake” Doughty.

Neither “The Avenue” nor the roller rink needs an introduction to West Baltimoreans.

It would be easy, in other words, to dismiss the entire orchestration as mere political theater (Hogan implied it was a historic occasion). It is, after all, taking place on the first day of early primary voting, and the governor, without a Republican opponent, is spending the entire day in the heart of Democratic Baltimore, taking headlines away from the opposition. Except, the handful of invitees who live or work in West Baltimore and speak on the governor’s behalf are clearly impressed by Hogan’s outreach and sincerity, including Shionta Somerville, principal at nearby Carver Vocational-Technical High School. Not just today, but over the past four years.

“After his second visit [to Carver], people asked me, ‘How is the Governor?’” Somerville says. “Not people at school but friends of mine outside of school,” she adds with a smile, garnering nervous laughter from the audience, which is fully cognizant that a white Republican governor isn’t likely to engender much affection in heavily Democratic West Baltimore. “I say he’s just down to earth and very charming. I’ve never been very big on politics, but I’m big on people.”

As unlikely as it would’ve sounded at this time four years ago, when he trailed Democratic nominee Anthony Brown by double digits in the polls, Larry Hogan—a first-time Republican elected official in one of the bluest states in the country—is now the second-most-popular governor in the United States. According to a Morning Consult poll this summer, 68 percent of Maryland voters approve of the job Hogan is doing. Only Massachusetts Gov. Charlie Baker, another Republican in a blue state, is more popular, by a single percentage point.

Of course, despite Somerville’s affection and kind words, and Hogan’s genuine talent for retail politics and relationship building, he is not going to carry Baltimore City this November. The overwhelming 10-1 Democratic registration advantage, and his original sins in the eyes of many in the city—cancelling the $2.9 billion Red Line transit project, breaking the decade-in-the-works $1.5 billion State Center redevelopment deal, holding back school funding weeks after the Freddie Gray uprising—are simply a bridge too far.

Also: Larry Hogan doesn’t need to win Baltimore. He didn’t in 2014. With broad support in the state’s suburban and rural counties, he just needs to mitigate the damage. So when Baltimore’s second-highest-ranking elected official, City Council President Jack Young, refuses to answer a reporter’s query about whether he will support the incumbent Republican governor or the Democratic nominee—it should ring alarms among the Democratic party faithful hoping to elect nominee Ben Jealous.

“You heard what people said. Look at his poll numbers,” Young says after offering words of praise for the governor in the lobby of the Shake & Bake as the Hogan event winds down. “I don’t have to tell you [who I’m voting for],” adds Young, suggesting he’s either a genuine fan of the governor, intimidated by his approval ratings, or both. “Who are you voting for?”

By now, most Maryland voters at least know the outline of Larry Hogan’s backstory. That his father, Larry Sr., was a U.S. Congressman and Prince George’s County Executive (also a former FBI agent and one of the first Republicans to come out against Richard Nixon after Watergate). That Hogan worked for his father and held a top appointment in the Republican administration of former Governor Bob Ehrlich, a friend since the pair were in their early 20s. That he was—and still is—the owner of a successful real estate company (while serving as governor, Hogan turned over leadership of his company to his brother and put his assets into a trust). And that he’s a self-described workaholic who didn’t marry until he was 48.

Less well known when he ran four years ago was that he’d run twice for his father’s old congressional seat and lost, which—silver lining here—meant he didn’t have to defend a voting record on Capitol Hill. It also effectively allowed Hogan to position himself as a political newbie in 2014 and an Anne Arundel County “small businessman.” He was anything but, obviously. He served as Maryland chairman of Youth for Reagan and four times as a delegate to the Republican National Convention, displaying sharp political instincts and a knack for savvy messaging from the outset of his stunning upset campaign. Hogan Companies have completed more than $2 billion in real estate deals since they were founded in 1985 and the governor has made roughly $2.4 million in combined corporate earnings and government salary since taking office.

Hogan had begun planting the seeds of what ultimately became his campaign when he launched a Facebook page in 2009 with the name Change Maryland and started trolling Governor Martin O’Malley—“Owe Malley” in red circles—over increases in state taxes, tolls, and fees, and the cost of regulations to businesses. That was five years before he announced his intent to run for governor. “Just a genius use of social media,” says Eberly, political science professor at St. Mary’s College in Southern Maryland. “I can’t think of anything like it before or since.”

In a recent interview at the Governor’s Mansion, Hogan says he was just frustrated at the time by the direction in Annapolis and didn’t necessarily intend to run for office himself. Borrowing from the opposition playbook, he took to Facebook after witnessing the Barack Obama’s groundbreaking use of social media. “It started to grow very quickly,” Hogan recalls. “I couldn’t find anyone I thought could win. [So], I decided to [jump in].”

Later, Hogan memorably—some would say cynically—dubbed an EPA-mandated, storm water management fee initiated by O’Malley “the Rain Tax,” honing his anti-tax message down to a three-word mantra. Avoiding hot-button social issues such as abortion and same-sex marriage that could potentially plague a conservative candidate in Maryland, Hogan—an Irish Catholic who personally doesn’t support the right to choose and says he has “evolved” on gay marriage—simply declared the subjects settled.

Hogan also vowed not to go after the new gun-control laws passed in the state under O’Malley in the wake of the Sandy Hook tragedy, and he has kept those promises. He even went further after the Parkland school shooting announcing he would support a “red flag” bill that would allow judges to temporarily require people to surrender firearms if they are deemed a danger to themselves or others.

Four years later, in his reelection campaign, he’s plugging positive job growth numbers in the state (although Maryland’s unemployment rate remains above the national average and neighboring Virginia and Pennsylvania), and his successful efforts to roll back tolls and push the first day of public school to after Labor Day.

“It’s been a pendulum swing from O’Malley,” says Jennifer Duffy, of the Cook Political Report, a national independent, non-partisan newsletter that analyzes elections. “Hogan doesn’t have an enormous record of accomplishment, and he’s not putting forth a grand vision for the second term, but he’s not raising taxes and he’s focused on deregulating rules for businesses. Maryland’s one of the wealthiest states in the country, has high-ranking public schools, and that’s enough for a lot voters who see no reason to change course.”

The attacks on O’Malley and the Rain Tax have also returned. The Maryland road signs Hogan changed after taking office still say, “We’re Open for Business.”

Hogan’s political success as a Republican governing a blue state is also something of a phenomenon, rarely seen in recent years outside of New England. (See Massachusetts governors Charlie Baker, William Weld, and Mitt Romney; Vermont Gov. Phil Scott; and New Hampshire’s Chris Sununu.) It has put him on the radar of the national Republican strategists who ponder the possibility of a Hogan presidential run—should a more moderate post-Trump GOP ever emerge.

“Larry Hogan is an interesting guy to watch,” says Rick Wilson, a longtime Republican strategist and author of Everything Trump Touches Dies. “He may not be on the radar of the average voter outside Maryland, but political nerds know him.”

“He’s charismatic, he’s a people person, and he loves to talk. He’s been that way for 35 years.”

To understand how Hogan ascended to the stunning position he’s in, which includes a 22-point lead over Jealous in last week’s Goucher College poll, it is worth remembering that he was not really known—think Q rating terms—even after he was first elected. In a low-turnout year, he won by garnering roughly 19 percent of the voting-age eligible population. Ordering the National Guard into Baltimore in the midst of the Freddie Gray uprising 97 days into his first term raised his profile, but he still was not a well-defined figure outside the political class.

That changed two months later when he held a press conference, his wife Yumi by his side, and informed Marylanders he had been diagnosed with an aggressive form of non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma after discovering a lump on his neck during a trade mission to Asia. Staying on the job despite the tough rounds of chemotherapy—his bald pate a visible testament of the battle—the newly elected Hogan, gregarious and self-deprecating by nature, proved more than just relatable to the average Marylander, but courageous as well. “The best news is that my odds of getting through this and beating this are much, much better than the odds I had of beating Anthony Brown,” Hogan joked during the announcement.

Now, there remains a narrative that Hogan’s bout with cancer, fraught as it could’ve been, remains at the core of his statewide appeal. Undoubtedly, it provided a sympathetic boost and a turning point in his approval numbers. But to credit his record popularity three years later to mere goodwill would be not just unfair, but a mistake.

“Let me preface this by saying I don’t think a cancer diagnosis is ever a good thing, for anyone, ever,” says Mileah Kromer, a Goucher College political scientist and pollster. “That said, a lot of people in the state didn’t really know who Larry Hogan was up until then—they hadn’t had time to fully shape an identity around him—and then that did it. Every family has been affected by cancer. His approval numbers were in the 40s at the time, and they shot up. That is all true. But to focus only on that is to miss Hogan’s gifts as a politician.”

Those gifts include Hogan’s remarkable skill in navigating a General Assembly with veto-proof majorities in both the state House and Senate, and dancing, on a nearly daily basis it seems, around the chaotic presidency of Donald Trump, the face of his party, just 35 miles down the road.

Democrats in Maryland, which Trump lost by 26 points, would love nothing more to tie Trump like a lead weight around the governor. Mostly, however, Hogan nimbly sidesteps the Twitter barrage and controversial policies coming from the other Pennsylvania Avenue—the one in D.C. But he has also taken some questionable positions and made some questionable statements for the leader of a blue state.

He remained mostly silent in the wake of the president’s Muslim travel ban and called efforts to limit state cooperation with ICE’s ramped-up deportation of immigrants “absurd,” for example. (In his first year in office, Hogan told the federal government Syrian refugees were not welcome in Maryland.) Two of his officials signed off on the state’s participation in a controversial Trump Administration effort probing alleged voter fraud. He joined embattled U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos on a visit to a Montgomery County school, but declined to comment on the nomination of Brett Kavanaugh to the Supreme Court, a pick many legal observers believe could imperil Roe v. Wade.

Most of these potentially polarizing episodes don’t stick to Hogan, however, and his ability to defuse problematic issues and appear pragmatic and reasonable have become a hallmark.

Hogan makes walking the difficult tightrope between the president’s words and deeds in more liberal Maryland almost look easy, says Richard Vatz, a professor of rhetoric and communications at Towson University. Stylistically, says Vatz, he’s able to alleviate middle-of-the-road Democratic voter concerns while not alienating the Republican base, by presenting himself as “not Trump” rather than “anti-Trump.” “When he does agree with the president’s agenda,” Vatz adds, “he goes out of the way to say he supports the policy, not necessarily the person behind it.”

“The real ‘Trump effect’ is that he is making Hogan look like a moderate,” Kromer says.

The General Assembly did override Hogan vetoes to pass a paid sick leave bill and higher renewable energy benchmarks, among other legislation, but overall he’s proved adept at avoiding losing fights in the state legislature, the importance of which he learned from his stint in the combative Ehrlich Administration. He maintains a solid rapport with powerful Senate President Mike Miller, who has known Hogan, through his father, since the governor was a teenager. “I let a lot of pitches go by,” Hogan says. “Where there is common ground, we work together.”

Hogan has let an automatic MVA voter registration, Planned Parenthood funding, and oyster sanctuary bills become laws without his signature to avoid veto override fights. He worked with the legislature to prevent Marylanders from losing their health care coverage following Trump Administration policy changes related to Obamacare and to oppose EPA cuts to Chesapeake Bay restoration funds. He collaborated with the General Assembly in putting together a $5-billion incentive offer to lure Amazon to Montgomery County.

But Hogan has also developed a knack for getting behind popular legislation he initially opposed. The fracking ban and the education lockbox amendment to the state constitution—which he now refers to as the “Hogan Lockbox” in a television ad—were first put forth and pushed by Democratic legislators. This week, Hogan began displaying a red apple, the trademarked logo of the 80,000-member Maryland State Education Association, on social media and campaign materials even though the teacher’s union has endorsed his Democratic opponent.

Hogan’s greatest gift as a politician, however, apparent to anyone who has crossed paths with him on the boardwalk in Ocean City, walking in Dundalk’s annual Fourth of July parade, or mingling at the Shake & Bake for that matter, is not his flair for branding or his political agility, as remarkable as those skills are. It’s a rare combination of personality traits for politicians: Hogan is not just an astute political animal, he is a happy warrior on the campaign trail, fun to be around, and disciplined off it.

No one has to ask the governor twice to pose for a selfie.

“He’s charismatic, he’s opinionated, he’s a people person, and he loves to talk,” says his old boss Ehrlich, who now works for the D.C. office of law firm King and Spalding. “He’s been that way for 35 years. Not all politicians are outgoing, but it helps, and he’s very outgoing.”

Hogan makes walking the difficult tightrope between the president’s words and deeds in more liberal Maryland almost look easy.

None of this, however, matters to progressive Democratic leaders and activists in Baltimore.

When Hogan brought his team to the Shake & Bake, local lay minister Glenn Smith, vice president of the Baltimore Equity Transit Coalition, led a small protest on Pennsylvania Avenue. Hogan’s spiking of the shovel-ready 14-mile, $2.9 billion Red Line transit project remains an issue because the lack of reliable public transportation remains the biggest impediment to employment in many neighborhoods, Smith says. “This was 13 years of planning, working with community leaders and community associations, and then just to come in and call it a ‘boondoggle,’ instead of, ‘How can we fix this? What can be improved?’ And to send $900 million back to the federal government—who does that?” says Smith, whose organization is trying to revive the once-in-a-generation initiative. “It felt punitive and mean-spirited.”

The governor admits no formal review document of the project was ever produced. State funds that would have been spent in Baltimore were diverted to highway projects in other parts of the state with higher concentrations of white residents, precipitating a civil rights complaint from the NAACP Legal Defense Fund and the ACLU, which the Trump Administration dismissed shortly after taking office.

At the same time, Hogan did green-light the Purple Line transit project, connecting suburban Prince George’s and Montgomery counties. Those two decisions together seemed to underscore a shift in the power structure in the state from Baltimore City to the booming D.C. suburbs.

Subsequently, the Hogan Administration’s $135 million effort to improve the MTA bus system in Baltimore has failed to become the “transformational” public transit system he promised. According to a study by the Central Maryland Transportation Alliance, on-time scores have not improved, and access to all jobs has marginally decreased since the change. More recently, an independent review after a four-week closure of the Metro Subway over potentially dangerous and long-ignored safety issues found troubling problems with the state transit agency, including poor inspection and maintenance practices and a failure to follow industry standards. Baltimore region commute times rank among the worst in country, surpassing even Los Angeles.

Meanwhile, Hogan, who says there are no new plans to address transportation woes within Baltimore City, has backed two high-speed rail projects, the Northeast Maglev and Elon Musk-pitched Hyperloop initiative between Baltimore and D.C, which further agitates some Baltimoreans. “The big problem for Baltimoreans is not getting to Washington, but getting across the city. Moving east-west has been a problem since the 19th century,” says former Johns Hopkins professor and Baltimore City historian Matthew Crenson. “The Maglev and Hyperloop make me furious.”

When Hogan opened his Baltimore City campaign office on North Avenue, City Council members Brandon Scott, Zeke Cohen, and State Delegate Brooke Lierman organized a counter press event across the street.

“There is a record here, and it is not a good record for Baltimore,” Lierman told the Real News Network, highlighting the Red Line, as well as the $1.5 billion redevelopment of State Center, now mired in lawsuits after Hogan’s decision to pull out of the deal. “I’m on the Appropriations Committee. Every year, it is a battle to make sure we are funding the priorities in Baltimore,” she added in an interview with the Real News Network. “Whether that’s the Baltimore Regional Neighborhoods Initiative, whether that’s funding for the Enoch Pratt, every year he cuts those initiatives out of his budget, and the General Assembly has to put that money back in and find money.”

Cohen, a former Baltimore City teacher and chair of the City Council’s Education and Youth Committee, said Hogan has underfunded city schools “somewhere in the range of $290 million to $360 million per year, depending on what study you follow” and alleged that when city school boilers “were bursting across the city and the children were in freezing classrooms . . . Governor Hogan was nowhere to be found.”

Cohen also called out Hogan for referring to unionized teachers as “thugs.”

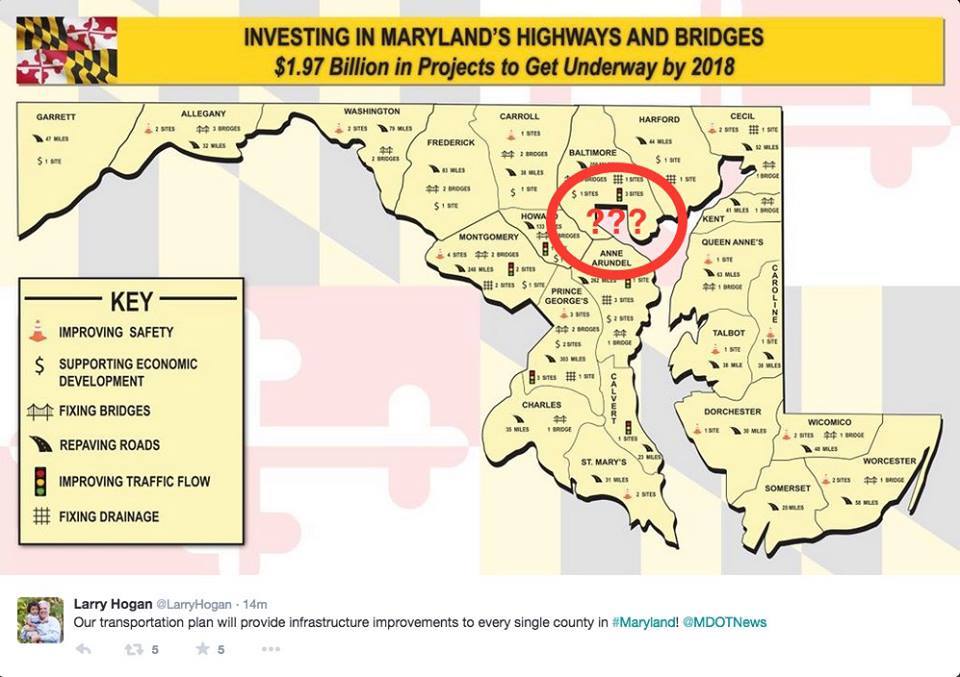

Dave Werkmeister, a 34-year-old IT sales professional and Patterson Park Neighborhood Association member, voted for Hogan four years ago. Hogan won the city’s first district, the geographical bottom of the so-called “White L,” and may very well do so again, but Werkmeister says he’s been disappointed in Hogan’s actions related to Baltimore. “[The Hogan Administration] put out a map of all the major transportation projects in the state, and literally Baltimore City had been removed from the map,” Werkmeister says. “Symbolically, that said everything to me.”

The low point, in terms of Hogan’s rhetoric toward the city, probably came during the trial of the first police officer in the death of Freddie Gray. On WBAL Radio’s C4 Show, Hogan expressed “concern” that while people were venting their frustration over the death of Gray, who had died in police custody, no one was protesting about the 330 other people murdered in city. As City Councilman Brandon Scott responded, that was not just factually wrong—given the 300 Men Marches, Enough is Enough rallies, Citizens on Patrol Walks, and litany of vigils and efforts—it was disrespectful to the thousands of residents who want nothing more than to quell violence in the city.

It was also dismissive of the troubling and criminal problems within the Baltimore Police Department, highlighted by a Department of Justice investigation and punctuated by the recent convictions of eight members of the department’s Gun Trace Task Force.

In 2015, Hogan’s top housing official, Kenneth Holt, told a gathering at the annual summer conference of the Maryland Association of Counties that he was looking to loosen state lead paint poisoning laws, suggesting current statutes could motivate mothers to intentionally poison their children in order to receive free housing.

“Larry Hogan may be doing a great job for other parts of the state,” Werkmeister continues. “And I am not about to tell someone who lives in another part of the state, in another county, that he’s not. I don’t know that. I live here.”

At some point, pollster Kromer believes, one way or another, the city’s high crime and poverty rates, criminal justice problems, school funding shortages, and lack of reliable transportation, affordable housing, and living-wage jobs—will have to be addressed by Hogan. If for no other reason than Jealous, whose parents have Baltimore roots and who needs a big turnout in the city for the race to be close, will bring it up.

Hogan would rather keep the focus on the State of Maryland than the state of Baltimore, Kromer says. “But Baltimore will be litigated.”