History & Politics

No Longer Underground

Historical sites along Maryland’s active Underground Railroad are being rediscovered.

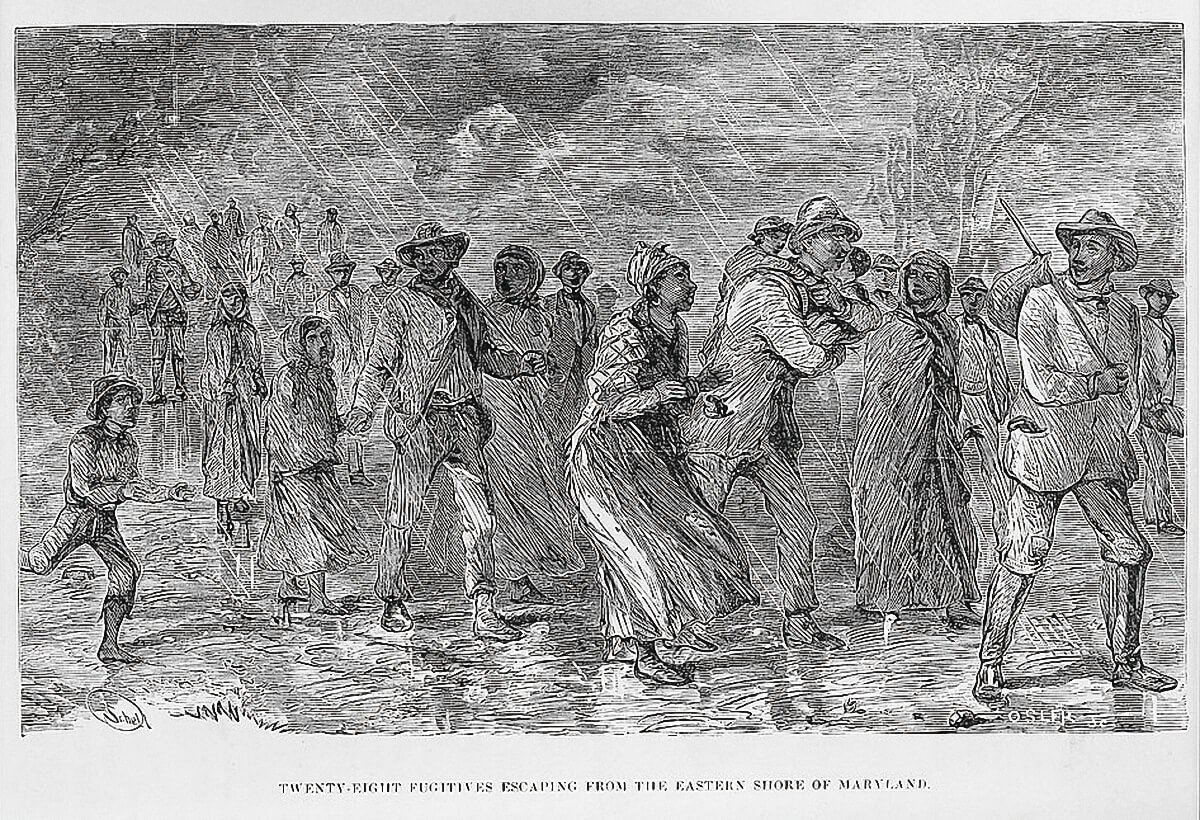

According to the 1860 Census, more than one out of five people living in Howard County was an enslaved person. First brought to the county to work in the tobacco fields, slaves were later used in the mining and production of iron in and around Elkridge. Simply put, over the century and a half that slavery was institutionalized and legally enforced in Howard County, a significant part of the economy was built upon the backs of enslaved African Americans.

At the same time, it was home to abolitionists and an increasing number of free Blacks in the decades leading up to the Civil War. Geographically, the area was centrally situated—between railroads and the Potomac and Patuxent rivers—serving as a way station on the Underground Railroad to free country in the northern United States and Canada.

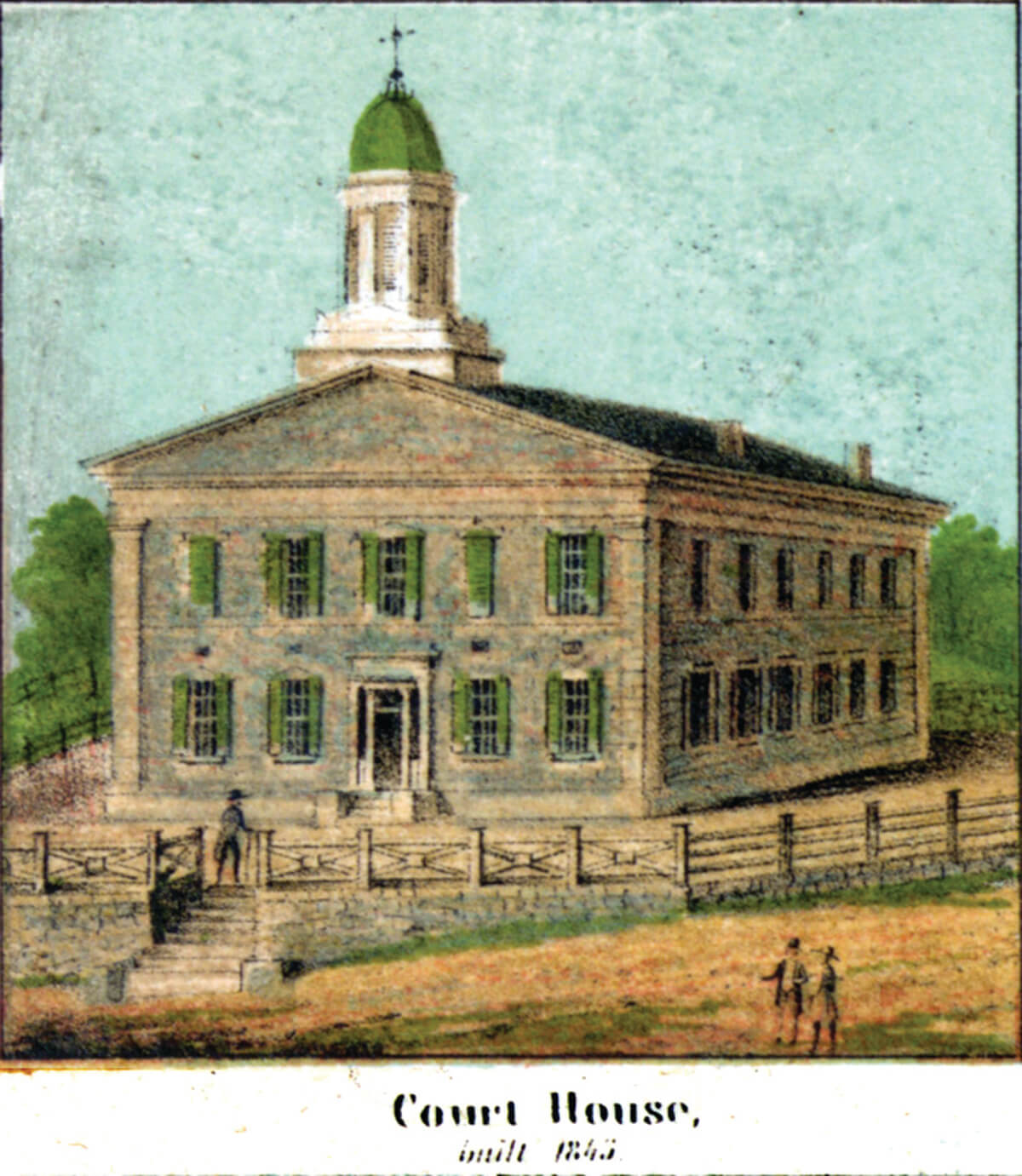

As a result, Howard County was also home to a jail, which remains standing, that incarcerated fugitive slaves. Additionally, it was home to a stone-built courthouse, which remains standing as well, that heard the cases of those charged with encouraging and assisting enslaved African Americans to flee their masters.

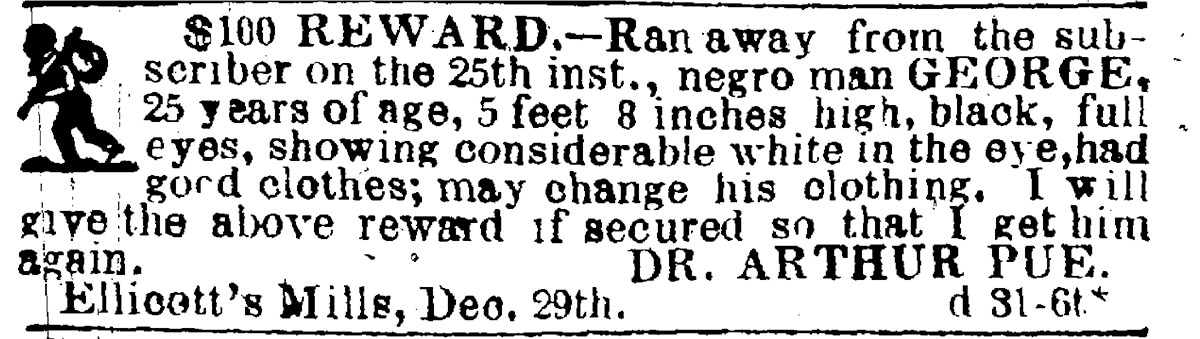

Built in 1851 and located at 1 Emory Street in the historic district of Ellicott City, the Howard County Jail held runaways, including Augusta Spriggs—who was detained while ads for her master in Prince George’s County to claim her went out—and Richard Martin, who was held as a fugitive without a pass. Augustus Collins was held here, too, while awaiting trial for inciting an insurrection among the Black population.

From its construction in 1843 to the end of slavery in Maryland on November 1, 1864, the Howard County Courthouse, also in the historic district of Ellicott City, held judicial proceedings related to legal cases involving those charged with encouraging enslaved persons to run away. Arguably, the most famous case here involved well-known Underground Railroad “general” William Chaplin of the American Anti-Slavery Society, who was arrested in August 1850 for having “abducted, stolen, taken, and carried out from the city of Washington” two fugitive slaves. But there were other cases, too, involving Howard County free Blacks such as Warner Cook, who was charged with enticing those enslaved to run away.

“These places and stories are important,” says Dr. Everlene Cunningham, chair of the Howard County Center of African American Culture, which curated the county’s The Simpsonville Freetown Legacy Trail. Named for the local community of early free Black landowners, the trail commemorates several places where oral history says Harriet Tubman led fugitives fleeing slavery, as well as the county’s historic jail and courthouse. “These are stories you didn’t get in school growing up.”

Maryland has the most documented successful escapes from slavery, and, in recent years, counties have been rediscovering—and highlighting—more historical sites in the state, considered the epicenter of the Underground Railroad.

Maryland has also been at the forefront of Underground Railroad research, documentations, and commemorations, which includes the now annual state recognition of September as International Underground Railroad month, signed by Gov. Larry Hogan two years ago.

That said, there’s no reason to wait until the fall to discover the indispensable role Maryland played in the Underground Railroad.

Howard County’s Network to Freedom and Underground Railroad

The Visit Howard County website highlights several stops on The Simpsonville Freetown Legacy Trail, including Locust Cemetery, where oral history says Harriet Tubman and the fugitive slaves she was guiding rested on their journey north. The cemetery is situated at the intersection of Harriet Tubman Lane and Freetown Road.

More information on the complete list of sites, as well as Tubman artifacts and belongings, can be found at the Howard County Center of African American Culture Museum in Columbia. The Center also sells Seeking Freedom: A History of the Underground Railroad in Howard County, Maryland, which was written by The Center’s since-deceased founder Wylene Burch, staff, and a team of researchers. The Center also hosts an exhibition on Maryland’s 4th United States Colored Infantry Regiment, which saw action in the Civil War in North Carolina and Virginia.

The Howard County Historical Society Museum on Frederick Road in Ellicott City also includes exhibits related to those who escaped from slavery in Howard County.

Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitor Center

It’s estimated that Harriet Tubman helped free 70 people over 13 trips back and forth to the Eastern Shore. The new Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Visitor Center in Dorchester County serves as a museum and gateway to the Harriet Tubman Underground Railroad Scenic Byway and provides visitors with the opportunity to walk in the abolitionist’s footsteps.

Among the destinations on the Byway are the Brodess Farm, where Tubman grew up in slavery; the Bucktown General Store, the site of her first act of defiance; the Tuckahoe Neck Meeting House, a gathering place for Quaker abolitionists—some of the most effective anti-slavery activists—and Tubman-Garrett Riverfront Park in Wilmington, Delaware, which honors Tubman and Thomas Garrett, who lived in nearby Quaker Hill.

Following In His Footsteps—Maryland’s Frederick Douglass Driving Tour

Organized online at the Visit Maryland website, this wide-ranging tour features sites from the Eastern Shore—where the famed abolitionist, writer, orator, and diplomat’s life began—to Central Maryland and the Capitol Region. (Douglass’ historic Cedar Hill home, now a museum, in Anacostia is not to be missed.)

Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey was born close to Tuckahoe Creek near Holme Hill Farm. Outdoor exhibits chronicle his early life here, as well as his enslavement at Miles River Neck and St. Michaels. Sites in Easton on the tour include the former Talbot County Jail, where Douglass was locked up for a week after attempting to gain his freedom by paddling a log canoe to the upper head of the Chesapeake Bay.

The Talbot County Courthouse in Easton, the location of Douglass’ famous “Self-Made Men” speech in 1878, honors him with a statue. Also on the tour site list: Bethel A.M.E Church and Asbury United Methodist Church, where Douglass also spoke in 1878.

“I am an Eastern Shoreman, with all that name implies,” Douglass once said. “Eastern Shore corn and Eastern Shore pork gave me my muscle. I love Maryland and the Eastern Shore!”

Among the key sites in Baltimore related to Douglass’ escape to freedom are the Frederick Douglass-Isaac Myers Maritime Park, which documents his life and working experience in the city, and the President Street Station (now home to the Baltimore Civil War Museum), where at 20 years of age in 1838 he successfully disguised himself and boarded a train for Philadelphia.

Hagerstown Underground Railroad Trail: Sites of Freedom and Resistance

From the mid 1700s through the Civil War period, African Americans were enslaved in Washington County, with about 14 percent of the population, or 3,200 people, enslaved in 1820.

Among those who escaped slavery here was James W.C. Pennington. He made it to Pennsylvania in 1827 at age 19, changed his name, eventually attended Yale University, became a Presbyterian minister, and officiated at Frederick Douglass’ wedding. Although he never returned to Washington County before the Civil War, he helped several members of his family escape as well, sheltering them and raising funds to secure their freedom. Pennington penned a memoir, The Fugitive Blacksmith (1849), and one of the first history books of African Americans, The Origin and History of the Colored People (1841).

Otho Davis also escaped slavery in Washington County. Taylor fled Henry Fiery’s Farm on Easter Sunday, 1856, taking his wife, two children, two brothers, a sister-in-law, and nephew with him on Fiery’s horses and two buggies, eventually reaching Canada. The Fierys attempted many times to get the Davises back, but to no avail, according to Visit Hagerstown, which has a downloadable local Underground Railroad map and brochure on its website.

The urban Underground Railroad trail in Hagerstown can be walked or driven, and takes visitors to sites associated with escapes from slavery, highlighting the individuals who fled and those who assisted in their escapes. There are several original buildings still standing—including Ebenezer African Methodist Episcopal Church, chartered in 1820—and the home of Sheriff William FitzHugh, who held people in slavery and enforced the law against those hoping for freedom.

Underground Railroad Experience Trail—Montgomery County

The trail, created in 1998 by Montgomery Parks to preserve the county’s rural landscape, provides walking paths and commemorates a part of Sandy Spring and Montgomery County’s Underground Railroad history.

The town of Sandy Spring was settled by Quakers in the 1720s, and they later banned members of the church from holding slaves. Eventually, a group of former enslaved people and the local Quakers worked together to help fugitive slaves to freedom, and it is said that Dred Scott stayed in Sandy Spring while the U.S. Supreme Court decided his famous 1857 case.

Among Underground Railroad destinations in the area are the Sandy Spring Slave Museum, which holds an actual slave cabin; the Sandy Spring Friends’ Meetinghouse, whose congregants were active abolitionists; and the Sharp Street Church, established in 1822 by newly freed African Americans. One of the stops on the trail is the Woodlawn Manor & Barn, built by a prominent family of local Quakers, who were banished from their congregation for refusing to free their enslaved workers.

Five years ago, the barn reopened as Woodlawn Museum, and today it hosts exhibits on the legacy of the Quaker community, the local African-American community, 19th-century farming, and Montgomery County’s Underground Railroad.

History, Heritage, and the Underground Railroad—Prince George’s County

African Americans have raised families and built communities for more than 300 years in Prince George’s County, which kept more slaves than any other county in Maryland. Of the more than 13,600 African Americans living in the county in 1860, some 91 percent were enslaved. Almost 10 percent of the fugitive slaves arrested in Baltimore were from Prince George’s County.

Among the historic sites here are the Northampton Slave Quarters and Archaeological Park in Bowie, which features the reconstructed foundations of slave quarters on the former Northampton Plantation. Excavations from the former plantation (1673-1860) have discovered artifacts from the lives of enslaved African Americans.

The Mount Calvert Historical and Archaeological Park in Upper Marlboro interprets the history of local Native Americans, the colonial town of Charles Town (Prince George’s first county seat), and the lives of African Americans. Fifty-one enslaved African Americans worked at the Mount Calvert Plantation by the mid 1800s. St. Paul’s United Methodist Church in Oxon Hill, believed to be the oldest Black congregation in Prince George’s County, was built upon property acquired shortly after the Civil War in 1867.

Among those who successfully escaped slavery in Prince George’s County was Nace Shaw, who fled the Upper Marlboro estate and plantation owned by Sarah Ann Talburtt in September 1858. Nace, who was 45 when he escaped, was also an unlikely candidate to flee given his relative privileged position as a plantation foreman, according to Maryland State Archives. But Shaw also had family in Washington, D.C., where he initially went before heading to Philadelphia and ultimately, Canada. “I wanted a chance for my life,” Shaw later said. “I wanted to die a free man.”