History & Politics

Nothing Less

Baltimore and Maryland women stood on the frontlines of the suffrage fight.

“Men their rights and nothing more; women their rights and nothing less.”

—Susan B. Anthony, whose last speech was given in Baltimore at the 38th annual Convention of the National American Woman Suffrage Association in 1906.

The afternoon’s events began when women from several states in the West and Midwest, already granted the right to vote, were invited to an informal meeting with President Woodrow Wilson at the White House. Afterward, those in the delegation on September 16, 1918, lavishly praised his words of support for universal women’s suffrage in the United States.

“I am, as I think you know, heartily in sympathy with you,” Wilson told the visiting women. “I have endeavored to assist you in every way in my power, and I shall continue to do so. I will do all I can to urge the passage of this amendment by an early vote.”

It sounded good. But the members of the more militant National Woman’s Party, based in Washington, D.C., including suffragists from Baltimore and Maryland, were not impressed when they received a copy of Wilson’s remarks two hours later. The president’s words fell far short of a promise of passage for what had become known as the “Anthony Amendment”—in honor of renowned women’s rights activist Susan B. Anthony—which had first been introduced some four decades earlier. In the spring of 1918, hopes had been briefly raised by similar encouragement from Wilson. Then, Senate leaders from his own party were once again allowed to filibuster the amendment.

For more than a year and a half, the National Women’s Party had been stationing “Silent Sentinels” to picket near the White House gates. The slogans on their banners highlighted the hypocrisy of Wilson zealously campaigning for democracy around the world while doing nothing to guarantee voting rights for half of his own country. The Sentinels braved cold and snow, spring downpours, Washington’s swampy humidity, as well as assaults by mobs angered that they had the audacity to criticize the president while the country was at war. They also faced arrests and increasingly harsh prison sentences, including abuse and solitary confinement at the infamous Occoquan Workhouse. They protested their conditions inside the prison with hunger strikes, and some prisoners, including women’s rights leaders Alice Paul and Lucy Burns, endured three-a-day force-feedings.

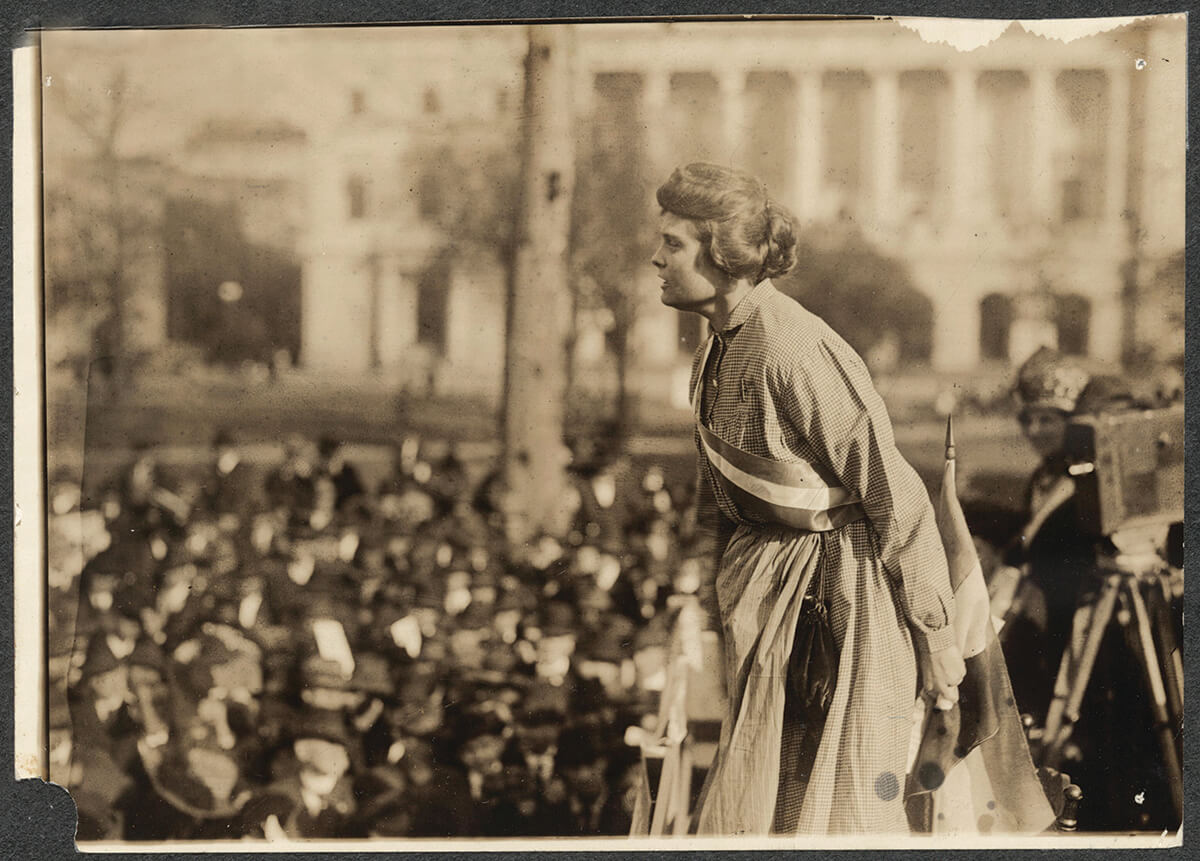

Now, some 40 members of the National Woman’s Party marched from their headquarters to Lafayette’s statue across from the White House, with their purple, white, and gold banners held high. There, 26-year-old Baltimore suffragist and NWP field organizer Lucy Branham held aloft a copy of Wilson’s recent statement in one hand and a flaming torch in the other. Branham, raised by a staunchly suffragist mother and physician father, had gotten involved in voting rights activities since earning her graduate degree from Johns Hopkins University. She’d been arrested during the silent picketing at the White House a year earlier and served two months in the District’s jail and Occoquan Workhouse.

“We want action!” Branham declared.

Then, she set a copy of the President’s statement ablaze.

“The torch which I hold,” she announced, according to dispatches that made national news, “symbolizes the burning indignation of women who for a hundred years have been given words without action.”

Branham would later participate in the NWP’s “Prison Special” tour of 1919 (see photo), when women who had been jailed for their activism traveled the country, typically in their prison dresses, to speak of their experiences. Her mother, also named Lucy, was later arrested, as well.

One hundred years ago this month on August 18, 1920, the 19th Amendment was finally ratified. Women had first organized and started collectively fighting for the right to vote on the national level seven long decades earlier, in July 1848, when suffragists, including Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Lucretia Mott, convened a meeting of more than 300 people at the Wesleyan Chapel in Seneca Falls, New York. The Methodist church was a haven for local antislavery activity, political rallies, and free speech campaigns. Frederick Douglass, one of the few men present, was also the only man invited to speak.

“The demand of the hour,” Douglass said, imploring the women to be bold, “was not argument, but assertion.” Shortly after the Civil War, these women activists began pressuring Congress to pass an amendment to the Constitution specifically recognizing their equal right to the ballot box.

The text of the amendment itself is uncomplicated and straightforward: “The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.” The struggle to get it passed was anything but.

“LIKE THE ‘ME TOO’ MOVEMENT, THEY STOOD UP AND DEMANDED TO BE LISTENED TO.”

“People with power, which in this case was men, do not give it up willingly,” says Jean Baker, Goucher College professor emerita and author of several acclaimed books, including Sisters: The Lives of America’s Suffragists.

Winning the right to vote would ultimately require the commitment, creativity, and courage of three generations of women. The journey was fraught and complex as they navigated the shifting political winds of the Progressive Era, not to mention recessions, wars, epidemics, and segregation. Suffragists were often compelled to align with reformers who had other political priorities—notably women’s prohibition groups—in an effort to broaden their support. Initially, they had allied with abolitionists. Later, white suffragist leaders banned Black women from their organizations in an appeal for Southern support where Jim Crow was already suppressing the vote of Black men by every means available.

Over the course of what must have seemed a struggle without end, suffragists continually tweaked their strategies and tactics. They relied on state and national conventions, parlor meetings, petitions, protests, marches, and acts of civil disobedience, including the refusal to pay taxes—throwing the Founding Fathers’ “no taxation without representation” admonishment at legislators—to draw attention to their cause. They printed pamphlets and started newspapers. Their PR shops constantly sent articles out to local and national dailies with the intention of changing the hearts and minds of the public. They deployed sophisticated lobbyists and pressured elected officials at every level when that failed.

“[The battle] is about political power and political will,” says Elaine Weiss, the Baltimore-based author of the award-winning 2018 account of the passage of 19th amendment, The Woman’s Hour: The Great Fight to Win the Vote. “The story of the suffragists is a bare-knuckled political tale with women as the lead protagonists. You don’t get that too often. Like the ‘Me Too’ movement, they stood up and demanded to be listened to.”

And they did it all before radio, television, and social media.

In Maryland, the state’s elected officials, as well as its leading newspaper, The Baltimore Sun, remained staunchly anti-suffrage for the entirety of the women’s movement for the right to vote—and then some, it would turn out. By the 20th century, the Maryland State Suffrage Association, the Just Government League of Maryland, and the Equal Suffrage League were all campaiging throughout the state. Members of the state organizations also joined the National American Woman Suffrage Association, putting their delegates on trains, not a comfortable mode of transportation in those days, and sending them to conventions around the country.

As in many parts of the U.S., Black women in Maryland formed civic organizations, including suffrage groups. Augusta Chissell, one of the founding members of the Baltimore branch of the NAACP, and Margaret Hawkins, a history teacher, were neighbors at 1532 and 1534 Druid Hill Avenue—the site of a new National Votes for Women Trail historical marker. They formed a committee known as the Dubois Circle, which meets to this day, and then the Progressive Women’s Suffrage Club to advocate for the enfranchisement of all women in the state. But members sought redress for other issues as well. After the 19th Amendment was ratified, Augusta Chissell penned an Afro-American column called “A Primer for Women Voters” to guide women.

“Many of the Black women advocating for suffrage were educators,” says Morgan State University archivist Ida Jones, a biographer of Victorine Q. Adams, Baltimore’s first Black councilwoman. “They were advocating for the right to vote, but they were also seeking the same pay for the same job white teachers were doing. They were trying to address the conditions of the city schools, wage, public education, housing, and health care inequality, many of the same issues as today.”

The pushback suffragists confronted was unrelenting. They were derided as radicals, socialists, communists, anarchists, Bolsheviks, and perverts, and mocked as unattractive and “unsexed.” Predictably, opposition came from male-dominated institutions—state houses, Congress, corporate interests, the legal community, and churches—but other sources as well that might be unexpected today. The National Association Opposed to Women Suffrage, which had state chapters, including one in Maryland, and headquarters in both New York and Washington, D.C., was founded by a woman. In fact, many organizations formed to oppose suffrage were led by women. (Suffragist women informally referred to each other as “suffs” and those opposed to voting rights as “antis.”) The most painful rebukes often came from their own families, who sometimes cast them out altogether.

Gladys Greiner, a young professional golfer and suffragist from Baltimore, was repudiated by her establishment parents in The Sun following an arrest in New York after marching with other suffragists in the city’s annual Christmas Day parade in 1919. “[We] regret very much that she thought it was her duty to take part in this silly parade,” her father was quoted, “which could not possibly result in anything except ridicule or pity for the misguided women who were tools of some other parties, who remained in the background.”

Even after the 19th Amendment passed in 1920, the battle continued in Maryland where a local judge sued the state to remove the names of two Baltimore women from the list of registered voters. His position was that the Maryland constitution granted voting rights only to men, and that the state was not among the 36 that ratified the 19th Amendment. Two years later, the U.S. Supreme Court rejected his claim. Meanwhile, the amendment was not ratified by Maryland until March 1941, and the vote itself not certified until 1958.

None of this opposition would have surprised Anthony, the pivotal women’s rights activist, orator, and lifelong social reformer, who had begun collecting signatures on anti-slavery petitions in the 1830s as a teenager. She made her last speech at the Lyric Theater in Baltimore during a convention of the National American Woman Suffrage Association in February 1906, having already trained the next generation of leaders.

“I am here for a little time only, and then my place will be filled,” the 86-year-old told the audience. “The fight must not cease. You must see that it does not stop. Failure is impossible.” Battling serious illness even as she delivered the speech, she died a month later, 14 years before the amendment named in her honor became the law of land.

“IS THIS JUSTICE?” MARGARET BRENT INQUIRED. “I ASK IN THE NAME OF YEARS TO COME.”

“The thing that strikes me most about these women is their optimism and their toughness,” says Baker, the retired Goucher professor, whose historically all-women student body was involved in the local suffrage movement. “Susan B. Anthony had pneumonia when she gave that speech in Baltimore. The women making these protests, making these long marches, being arrested and incarcerated—not wanting their families to pay their fines—were for the most part, white middle-class women who were not accustomed to that kind of physical hardship.”

“Remember that a very small minority supported their effort, initially,” Baker continues. “They went out to change public opinion, and kept at it during World War I, which was not necessarily seen as the most patriotic thing to do, and they were attacked.” In particular, they were accused of not being womanly enough. “The most common complaint they heard while protesting was, ‘Who is raising your kids? Who is taking care of the house? Who is at home cooking your family dinner?’ Nonetheless, they are in perpetual motion.”

Although the suffragists had been the first to organize for the right to vote in the United States, the first woman in America to actually claim the right to vote preceded them by two centuries, and she was from Maryland.

Margaret Brent’s story is not well known despite the fact there is a Baltimore City elementary/middle school on St. Paul Street that bears her name.

Leonard Calvert, the first proprietary governor of the Maryland province and Lord Baltimore’s brother and attorney, had named the never-married 47-year-old Brent—a large St. Mary’s landowner and successful entrepreneur—the sole executor of his will. (If she had married, all her holdings would’ve automatically become the property of her husband.)

Several months after Calvert’s passing, assuming his position as legal agent of Lord Baltimore, she strode before the nascent colony’s Assembly on January 21, 1648. Ms. Brent claimed not only control of all rents due to Lord Baltimore, but also the right to two votes in the Assembly as both the legal representative of Lord Baltimore and landowner herself.

The first claim, that she possessed the legal authority to act as legal agent of Lord Baltimore, was upheld by the all-male Assembly. The second claim, the right to any vote, let alone two, was rejected.

“Is this justice?” she inquired of those men seated at the colonial gathering. “I ask in the name of years to yet come. Ye have prided yourselves on being the only colony within the New World which grants to every man the right of worshipping his God as he wisheth. Ye boast of your liberty and freedom and are proud ye lead the way of right. Lead it in this likewise, build wisely, grant us justice, and let the woman who hath equal risks with ye in this new province have an equal voice in the government. Else is your boast as empty wind.”

Lucy Branham could not have said it better.