History & Politics

Though the Exterior of The Peale is Relatively Modest, The Story Inside Is Anything But

Shuttered for much of the past quarter century, the museum officially reopens (again) on August 13 following a $5.5-million overhaul.

The first museum building in the Western Hemisphere can be easily missed. Situated behind beautiful Zion Lutheran Church, which has maintained German-language services for more than 265 years, and in the shadow of historic City Hall, the exterior of The Peale is relatively modest.

The story inside the four-story, red-brick Federal Period townhouse is anything but.

The brainchild of painter and innovator Rembrandt Peale, acclaimed for his astonishing likenesses of contemporaries George Washington and Thomas Jefferson, The Museum and Gallery of Fine Arts opened a month before the British attack on Fort McHenry. Two years later, Peale fired up a gas-fueled chandelier in his repository of fine art and curiosities—recently discovered mastodon bones, for example—and convinced several local businessmen to launch the nation’s first gas company, aka BGE. Then Peale and friends talked city officials into making Baltimore the first city in the U.S. with streetlights.

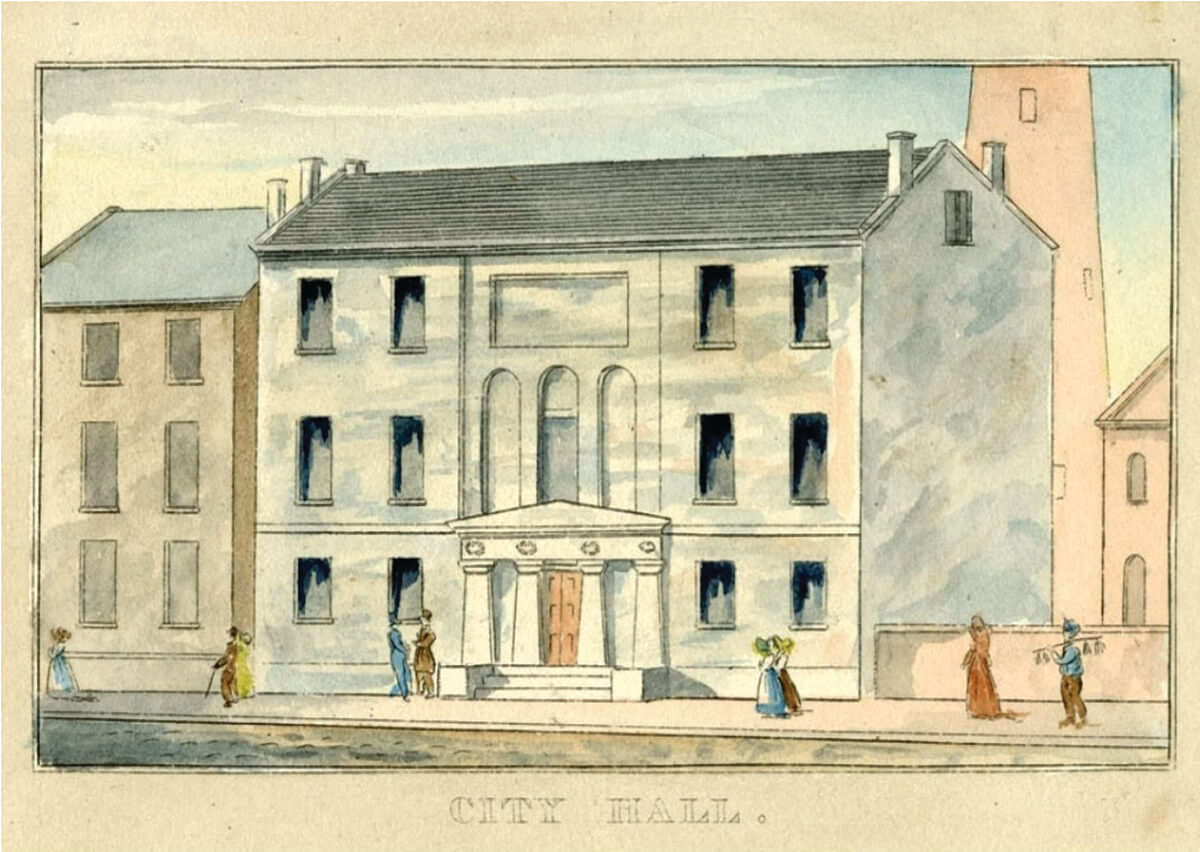

More interested in European painting techniques and science of all sorts than paying his mortgage, Peale soon turned museum operations over to his brother Rubens. (Rembrandt Peale was preordained to be an artist like his father, Charles, as were his siblings, whose names included Rubens, Raphaelle, and Titian.) Rubens Peale brought in live animal acts to attract crowds, but ultimately the Peales closed their museum, selling the building to the burgeoning Baltimore, suddenly in need of a formal City Hall in 1830. The mayor and council finally outgrew the townhouse and moved down the street into our current City Hall in 1875, at which point change would become a constant for the Peale building.

Next, it served as host to Male and Female Colored School No. 1, the first designated “colored” high school in Maryland. Later, the Baltimore water department assumed control of the property. In 1916, the space became home to shops and light manufacturing.

This part sounds thoroughly modern: Along the way, the now-iconic building was twice condemned by officials, only to be saved by public outcry each time. Eventually, it was rehabilitated and rebranded the City Life Museum, but then that closed in the late 1990s because of budget cuts. Which brings us to today: Shuttered for much of the past quarter century, The Peale officially reopens (again) August 13—on the 208th anniversary of its original opening—following a $5.5-million capital campaign and top-to-bottom overhaul, an effort begun by the Friends of The Peale in 2008.

The mission of the new Peale centers on another evolution, as a community-driven museum, repurposing the historic building as a celebration of the unique history of Baltimore, its denizens—and fittingly, its one-of-a-kind buildings.

“We won’t do ‘top-down’ curated shows more than once a year,” says Nancy Proctor, The Peale’s chief strategy officer. “We operate quite differently from a traditional museum approach. Everything that happens in the building will be proposed by a community member. Exhibitions and performances are all grassroots-driven.”

Recent exhibitions include “THE AMAZING BLACK MAN,” a solo exhibition by local artist Kumasi J. Barnett, who painted over old Marvel and DC comic books, replacing past heroes with characters such as “The Amazing Black-Man.” In June, the museum hosted the Single Carrot Theater, which performed Marie Antoinette and the Magical Negroes, a high-fashion, time-jumping exploration of race and revolution in America, set against 16th-century Versailles and the French Revolution.

Board member Mortimer “Tim” Sellers, a descendant of Rembrandt Peale, believes in the museum’s new direction. Its 50-year lease with the city, similar to several other historic venues, is also a welcome development.

“The Peales thought of themselves as scientists, as well as artists, and they were in touch with all the cutting-edge and experimental things happening,” Sellers says. “When the idea of gas lighting became possible, they instantly tried to do it. But I’m not sure Rembrandt was a particularly good businessman. The family lost any connection to Baltimore Gas and Electric.

“That’s typical, though,” Sellers continues with a laugh. “I’m speaking of his family, but it’s my own family, too. We’re all creative and very involved in life and innovation, but we’re not particularly good at focusing on making any money out of it. I mean, I guess it’s more fun to discover things than it is to actually figure out how to monetize them. There’s a downside, which is to say to we remain poor.

“You asked what I do for a living? I’m a philosopher. I’m an academic at the University of Baltimore. So, there you have it.”