Travel & Outdoors

Bay Window

Photographer Jay Fleming captures the world of water on the Chesapeake.

In the middle of the Chesapeake Bay, where Maryland waters idly slip into Virginia, time stands still on the remote archipelago of Tangier Island. An hour’s ferry ride from the mainland, there are no cars, no hospital, two churches, one schoolhouse, and limited cell phone service, where voices still lilt with the hint of an English brogue.

It’s a place so small—shrinking more and more each year in part to climate change—you can almost see across it, and when visitors arrive, some can’t help but feel a sense of voyeurism, having ventured out so far to set eyes on this bygone way of life, which might actually disappear in the next half century.

Not Jay Fleming, though. Wearing a pastel sun shirt, Under Armour sneakers, and polarized sunglasses, he whips up to the Tangier pier on a borrowed golf cart and shoots the breeze with a pair of locals picking leftover crabs on their lunch break. The 34-year-old Annapolis photographer with some 10,000 book sales and 18,000 Instagram followers is somehow not an outsider here.

“He calls me ‘shithead,’” says Fleming with a boyish grin, nodding to an old timer at the oil shop before peeling off to grab his gear and head north to nearby Smith Island. His boat—a sleek gray Privateer with a 200-horsepower Suzuki motor—is meant to cut through the capricious waters of this widest part of the Chesapeake, and coming here for more than a decade, he now knows the channels, shallows, and tides, plus the best spots for finding arrowheads and foraging wild asparagus. After weeks between the islands, though, he’s now eager to get home, having just wrapped a string of six workshops and the final photographs for his upcoming book, Island Life.

“I haven’t driven a car in a month,” says Fleming, his skin tan and dark curls tangled as he steers into the wind toward the Maryland line. “Smith Islanders call this my peeler run”—comparing his recent work hustle to the waterman’s shoulder season of soft-crab harvests—“I’ve made some real friends here.”

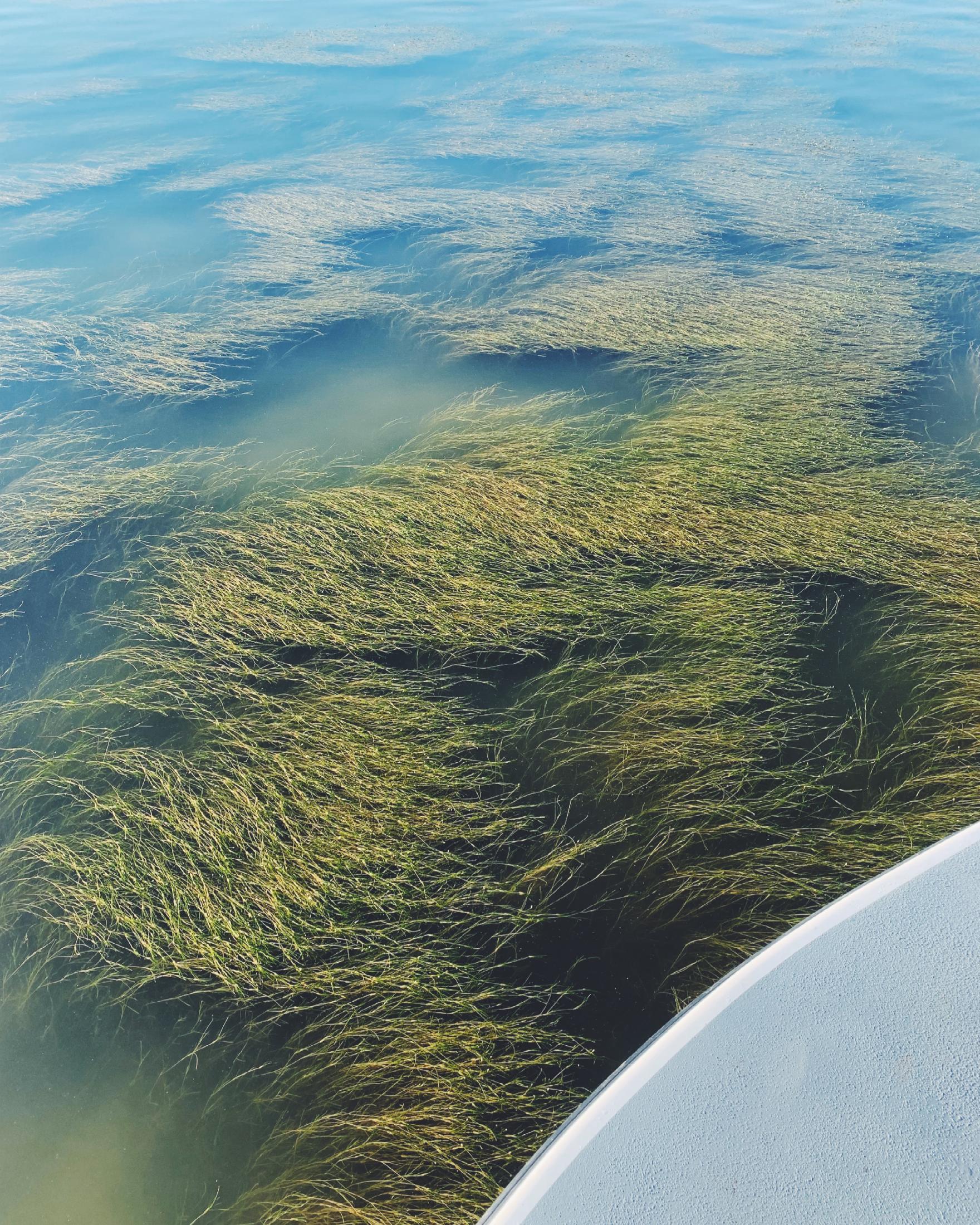

This place, these people, the water. It is all peak Jay Fleming. A rightful heir in the lineage of iconic Chesapeake Bay photographers—A. Aubrey Bodine, Marion E. Warren, Robert de Gast, David Harp—he has spent the past decade gaining a loyal following for his visual storytelling that offers windows into the nation’s largest estuary that even many lifelong residents have never seen: underwater terrapins, newborn egrets, shedding blue crabs. Moonlit lighthouses, Bay Bridge sunrises, a haunting series on the last house of Holland Island. Now, as his time on Smith and Tangier shows, his bread-and-butter is the people of the Chesapeake.

“I’m not reinventing the wheel, people have done what I’ve done before,” says Fleming. “But rather than carry a torch, I’m trying to find a way to make my own work stand out.”

His work—low to the water, soft light, vibrant colors, strong reflections—has become almost instantly recognizable, and in part that is because of his commitment to capturing the image by any means necessary—on land, underwater, by kayak, in airplanes, through storms, before sunrise, even neck-deep in pound nets full of menhaden.

This aquatic comfort zone makes sense once you learn about Fleming’s upbringing. Growing up between Annapolis and Lewes, Delaware, he has been a lifelong river rat, swimming and fishing and boating as far back as he can remember, with his own kayak at the age of 15 scratching a growing itch to explore the water further. On evenings and weekends, he’d head out with rolls of film and a hand-me-down Nikon from his father, Kevin, an award-winning photographer for National Geographic, who also had an affinity for the great outdoors.

“. . . RATHER THAN CARRY A TORCH, I’M TRYING TO FIND A WAY TO MAKE MY OWN WORK STAND OUT.”

Equal credit goes to his mother, Carla, a director for the Department of Natural Resources, where Fleming interned in high school. After graduating with an economics degree from St. Mary’s College—“I was going to be a biology major but almost failed my first semester”—and a stint with the National Park Service at Yellowstone where he ran a gillnetting boat to catch invasive lake trout, he landed back at the DNR in seafood marketing. Here, he helped launch the “True Blue” program to promote local sourcing and got inspired with the idea for his first book.

“And the rest is recent history,” he says, now shooting on a digital Nikon D850.

But for three years, Fleming shadowed watermen and captured hundreds of thousands of photographs to create Working the Water, a photojournalistic narrative of the people—from watermen to crab pickers to boat builders—who make their livelihoods on the Chesapeake. Since its self-publication in 2016, it has become a coffee table staple around the watershed, initially selling out in its first 40 days and now in its fourth printing.

Those watermen, in particular, have become a niche for Fleming, and their notoriously cautious communities have largely welcomed him with open arms. He has been invited to birthday parties and church services, taken the local preacher out snorkeling, and often eats seafood with the family of Mary Ada Marshall, his sort of unofficial godmother and the high priestess of Smith Island cakes, whom he also hires to teach his workshop students—mostly amateur photographers—how to make the classic dessert. Many wear the honor of being featured in a Jay Fleming photograph like a badge, with his images framed in households, displayed at funerals, and used at farmers market stands to help sell their fresh-caught fish.

“Catchin’ red drum out here!” calls out local crabber Allen Marsh, looking up from his docked workboat on Smith Island’s tiny hamlet of Ewell as Fleming ambles in alongside him just before sunset.

“Any big ones?” asks Fleming, who has grabbed his own fishing rod in hopes of an evening catch.

“About 10 pounds,” says Marsh, before turning back to the work at hand.

The next morning, Fleming will shadow Marsh’s soft crab harvest, as he has many times before, seamlessly maneuvering around the long iron chain of the scraping dredge with barely a ripple, just another fish in the water as he sets his boat in neutral and slides between the bow and stern to get his shots.

“When Jay shows up, there’s low tides and no crabs,” cracks Marsh as he sifts through his haul for market-size soft-shells, finding a few keepers.

“People have this preconceived notion that watermen are tough to get along with, and I don’t think that’s the case—as long as you don’t demonize what they do,” says Fleming. “I don’t have a political agenda or an environmental agenda. I just show things as I see them. I hope my work can be an educational tool and help people make their own opinions.”

Of course, given his public following and proximity to the water, it would be easy for Fleming to become a voice for either of these Chesapeake stakeholders—the watermen or the environmentalists—particularly as the two parties continue to quarrel over the management of the bay’s natural resources, and while the estuary’s overall health continues to ail, receiving a “C” on its latest annual report card by the University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science.

“The bay is in trouble and humans are the cause of it,” says Fleming, “but I’m just a fly on the wall.”

Still, it was these undeniable changes that brought him down to the islands in the first place, drawn by a Facebook post featuring pictures of old headstones washing away on the now-abandoned Tangier “Uppards.” He arrived with his kayak via the mainland mailboat, paddled north to this spit of marsh, and camped out overnight to capture the drowning cemetery at low tide.

“I DON’T HAVE A POLITICAL OR ENVIRONMENTAL AGENDA. I JUST SHOW THINGS AS I SEE THEM.”

“Maybe I have a knack for photographing things that are on the edge,” says Fleming, pointing to the images in Island Life, a visual narrative over a decade in the making of these last two inhabited off-shore islands. “I hate to say it, but these photographs will be historical in 50 years. An inventory of what’s here now.”

Which is in part what keeps him out here, on the water—this idea of documenting the way things were. At some point, he would like to create a series on issues the Chesapeake faces, such as pollution: “You’d be amazed at how many balloons you find out here,” he says. Or invasive species: “Blue catfish are a big threat to the ecology of the bay.”

For now, he’s all packed up and headed back to his car in Crisfield—his boat’s hull full of backpacks, camera cases, and a single, safely secured Smith Island cake—navigating the swells of northeast wind gusts, soaking wet by the time he reaches shore. This weekend, he’ll make his way down to Chincoteague, Virginia, for two more workshops, then get to work on final proofs for his new book.

“Every day is different,” says Fleming. “It’s definitely better than sitting behind a desk.”

Back in his office in Stevensville, a salon wall of framed photographs showcases his own work, plus magazine covers, pictures with Governor Hogan and Senator Van Hollen, and a candid shot alongside Art Daniels, the late Deal Island skipjack captain and first waterman to take Fleming under his wing.

Shelves of vintage cameras and oyster cans mingle with boxes of his dad’s old slides, while a massive Epson printer inches out images to be framed and hung in homes, offices, and restaurants like the True Chesapeake Oyster Co. in Baltimore.

Island Life will hit stores in October, but on this July afternoon, red pen marks dot a draft of its 280 pages, with Fleming having spent the weeks after his return from the islands sifting through images, writing captions, and taking the occasional nap. Come fall, he’ll host book signings and museum exhibitions, with most of the word spread through social media, where, even in a sea of images, his followers only continue to grow.

“Facebook and Instagram have been such incredible tools to reach people,” says Fleming. “I can run my social media from my boat.”

He relishes that freedom, the ability to be his own boss and dictate his own schedule—following the weather or harvests or next whim of inspiration, which doesn’t seem to be drying up anytime soon. This month, he’ll visit Maine to shadow lobstermen for his next book on the fisheries of the Atlantic Coast. But these local waters will still always be home.

“There are so many ways to tell a story here,” says Fleming. “I’ve been able to see so many things I wouldn’t have otherwise, and it’s given me a better understanding of the Chesapeake Bay. But anybody could do what I do, really. You just have to go out there and see it.”