Arts & Culture

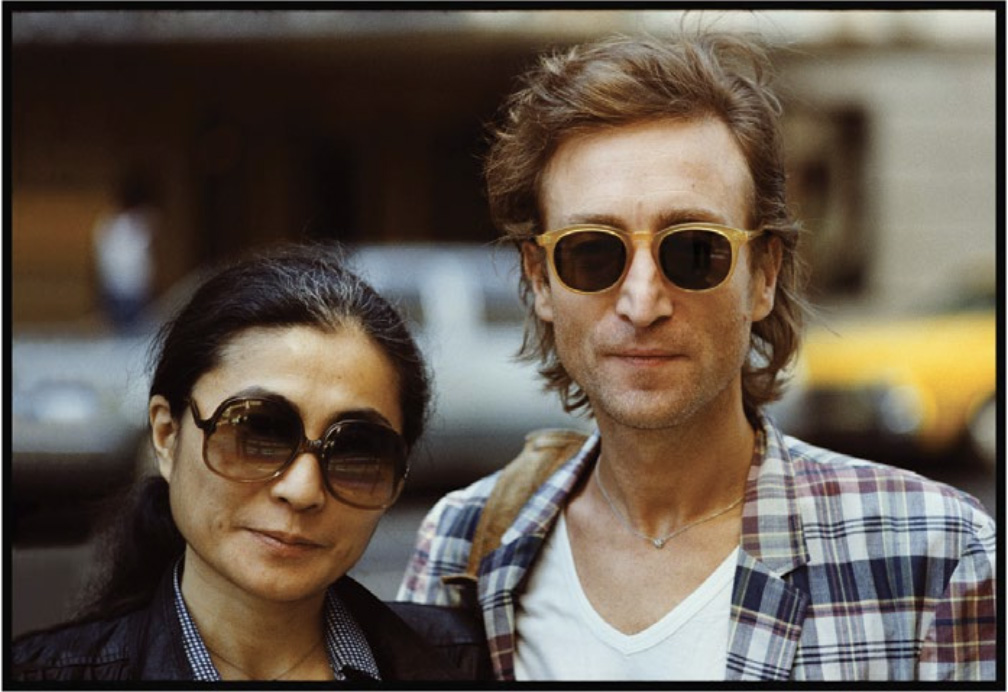

A Baltimore Photographer Once Captured John Lennon and Yoko Ono at The Dakota

"C’mon, Mister-all-the-way-from-Baltimore, you can do this," Stuart Zolotorow remembers Lennon telling him.

When John Lennon’s antiwar politics earned him a place on the Nixon White House “enemies list,” Pikesville teenager Stuart Zolotorow rallied to his cause.

Lennon and Yoko Ono had been living in New York for a year by the time Richard Nixon ran for re-election in 1972. Opposition to the Vietnam War was peaking and the former Beatle and his wife were singing “Give Peace a Chance” at antiwar demonstrations and telling their fans that the best way to end the war was to cast a ballot against the sitting president. Concerned Lennon might sway newly minted 18- to 20-year-old voters, the Nixon Administration responded by wiretapping him and ordering his deportation over a trumped up cannabis charge back in England.

Lennon’s immigration attorney, Leon Wildes (by coincidence Zolotorow’s rabbi’s college roommate), believed a public petition would help champion his client’s cause. An aspiring guitarist at the time, Zolotorow went to work, spending two years gathering signatures for The National Committee for John and Yoko before the deportation order was finally revoked in 1975.

“There were petition pages in the back of a [music] magazine, my father was a rep for the publisher, and that’s how I got started,” Zolotorow recalls. “I’d get signatures from everyone, firemen, police officers, college students. I would send one or two petitions to New York and they would me send me one or two back.” He also stayed in touch with one of Lennon’s and Ono’s assistants.

Fast forward five years. Zolotorow heard that Lennon, who had taken five years off from the hustle and bustle of the music industry to help raise his youngest son, was recording again—what would become his acclaimed Double Fantasy album. Now 24 and a budding photographer—Zolotorow was employed at the Zepp Photo Center in the Reisterstown Plaza and shooting the occasional concert at the old Painters Mill Music Fair—he pitched the idea of traveling to the Big Apple to snap a picture of Lennon and Ono to the couple’s assistant. The assistant did not encourage Zolotorow to make the trip, but did say he could use her name if he made the pilgrimage.

Forty years ago this fall, shortly before Lennon was killed on Dec. 8, 1980, he did just that. “I took the train up, walked into The Dakota [apartment building], and told the doorman to tell them it’s Stu Zolotorow, I’d come all the way from Baltimore, and gave him the assistant’s name. I told him if he rang them, I’m sure they’d say they were expecting me.”

Not exactly true, though Lennon said that they’d be down in 10 minutes. When they reached the lobby, Zolotorow handed him a mock album cover he’d made with a photo of Ono and their son Sean, which broke the ice. Then Lennon explained they happened to be working on a song (“Beautiful Boy”) about Sean.

“When they came downstairs, I asked if we could go outside for the photograph,” Zolotorow says. “I was so nervous I kept fumbling with all my equipment. The harder I tried, the worse it got. But John saw how nervous I was and made jokes and laughed and tried to put me at ease, which was impossible. He said, ‘C’mon, Mister-all-the-way-from-Baltimore, you can do this.’ Then he told me to take an extra shot to be sure I got something good.”

Zolotorow got one great shot (above), which he sent to Linda McCartney after Lennon’s death. When she included it in a magazine she edited, it became his first published photo. “I was not, and I’m still not, very political,” Zolotorow says. “I relate more to John as an artist and musician. But he was a beautiful person. All he said was ‘Give peace a chance.’ How can you not like a guy like that?

During the brief shoot, Zolotorow, who went on to photograph Sinatra and Springsteen in his four decades as a professional lensman, noticed a small crowd had formed outside The Dakota as he struggled to capture the famous couple. Turning back, he realized that one of the women standing in the group was Gilda Radner.

“So I asked if I could take her picture,” Zolotorow recounts. “She had seen everything that had unfolded with John and Yoko. She said sure, ‘As long as you can pull yourself together before my ride gets here.’”