Arts & Culture

Station North Books is Baltimore’s Most Eccentric Book Shop

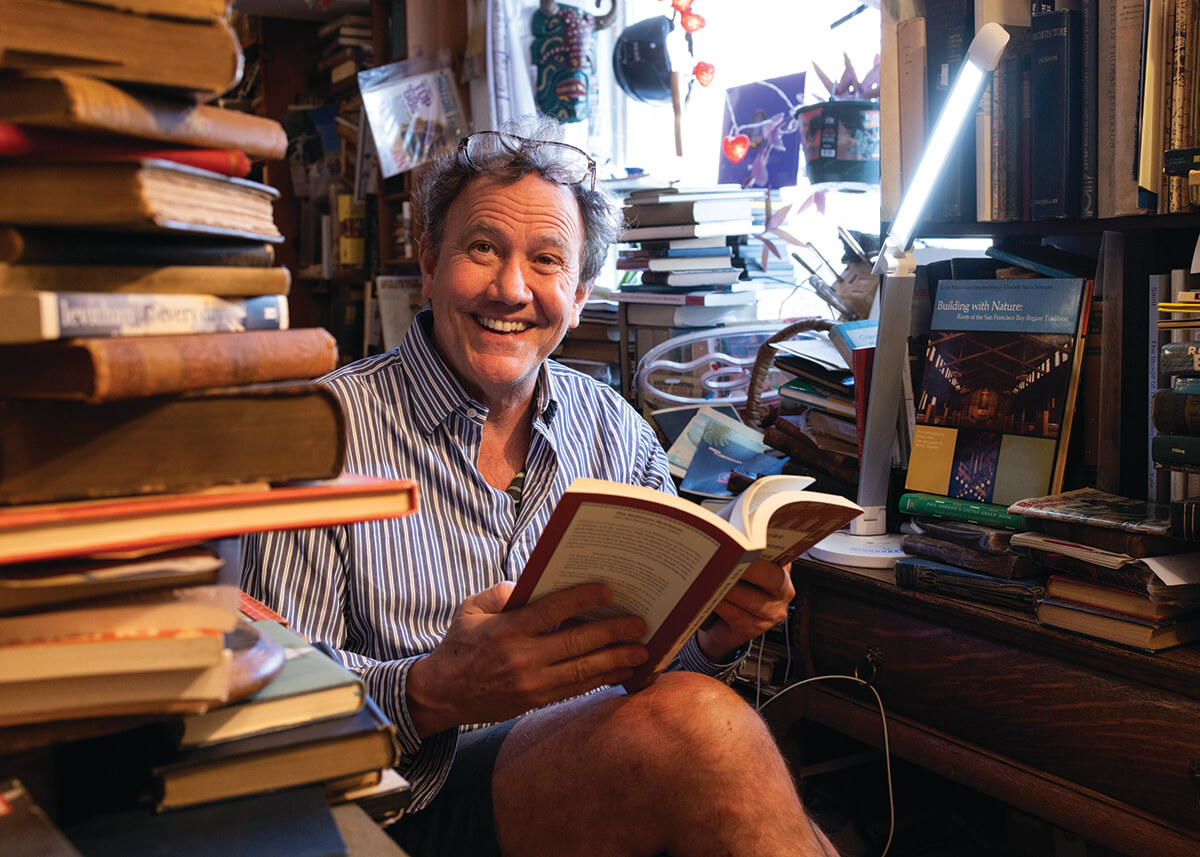

Owner Ned Sparrow takes a treasure-hunt approach to filling his tight shelves, which showcase an almost unimaginable range and depth of offerings.

On the north side of a side street around the corner from Baltimore’s Charles Theatre, half-hidden by potted plants, milk crates crammed with vintage LPs, and piles of books atop folding chairs, is the red door to Station North Books. The windows on either side are filled three-quarters high with haphazard displays of books, Christmas lights, picture frames, and more books, not so much stacked as packed against the glass, as if the shop was run not by a bookseller but a book-hoarder, which is probably accurate.

“I have an accumulative streak,” says Ned Sparrow, 58, who opened the shop a half-dozen years ago, after a career as an English professor at nearby Maryland Institute College of Art.

Open the door, go down a narrow passageway hemmed in by bookshelves and tables loaded with volumes—new and used, paperback and hardcover, antique and simply well-read—and you’ll find Sparrow, likely sitting in the crowded back room of the 800-square-foot shop, wedged into a chair near signed copies of novels by John Updike and Cormac McCarthy. He keeps his older books toward the back as well, handy as it were, “close to the guitar and the fire extinguisher.”

Until recently, there was also a sign on the front door that said, “Going out for business,” which engendered concern among some of the city’s literati. To be clear: The shop is not closing, at least not anytime soon. It is a grammarian’s joke.

“I was reading the want ads,” says Sparrow, “and one of them said, ‘Going out for business.’ And I thought, ‘That’s a really dirty trick.’ And then I’m like, ‘Well, nobody’s coming in.’ And some of them did come in because of that.” He has the grace to look somewhat sheepish. “I’ve been an abecedarian and a pedant for a long time. I felt bad tricking people, kind of, but I also felt like, eh, it’s okay.”

A tall man with a mess of wavy hair and an infectious grin, Sparrow turns to make an espresso on a tiny, pump-driven espresso machine jigsawed into a network of books up against a rear wall. A demitasse appears, somehow, from a shelf that seems only to hold more books.

His friends say that the literary clutter goes with the territory.

“[Before he opened the bookstore], his house looked like a glorified book quarter. I can remember going up there, and you sort of had to carry your own light to go through the books because there wasn’t enough light to see everything,” says Edward Whitfill, who has known Sparrow since 2006 and who ran Ukazoo Books in Towson for 14 years until it closed in 2021. “He had this attic that was so jammed, you could barely go through it,” continues Whitfill. “So I was happily surprised when he finally made the move and decided to start offering those books to the public and not just online.”

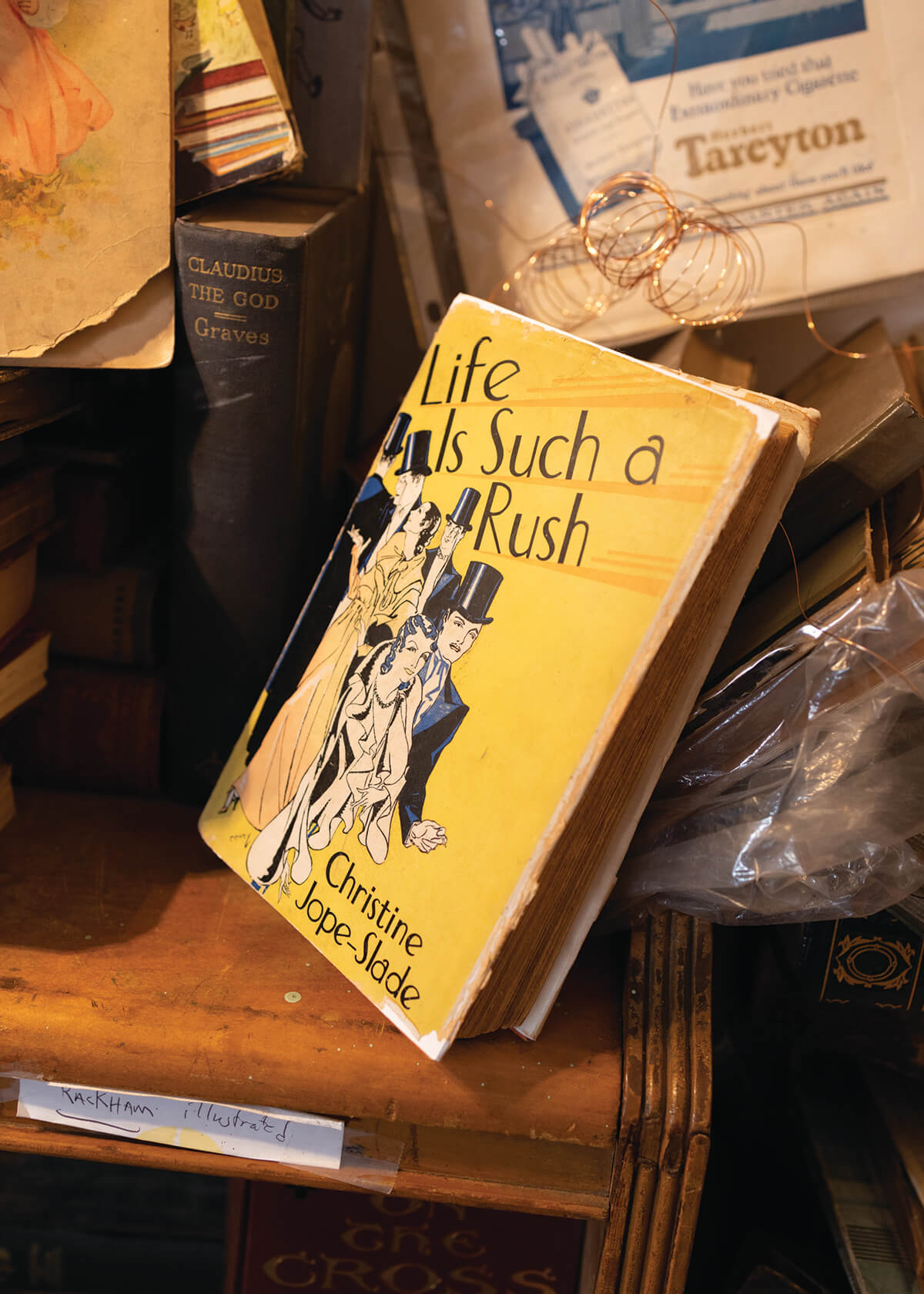

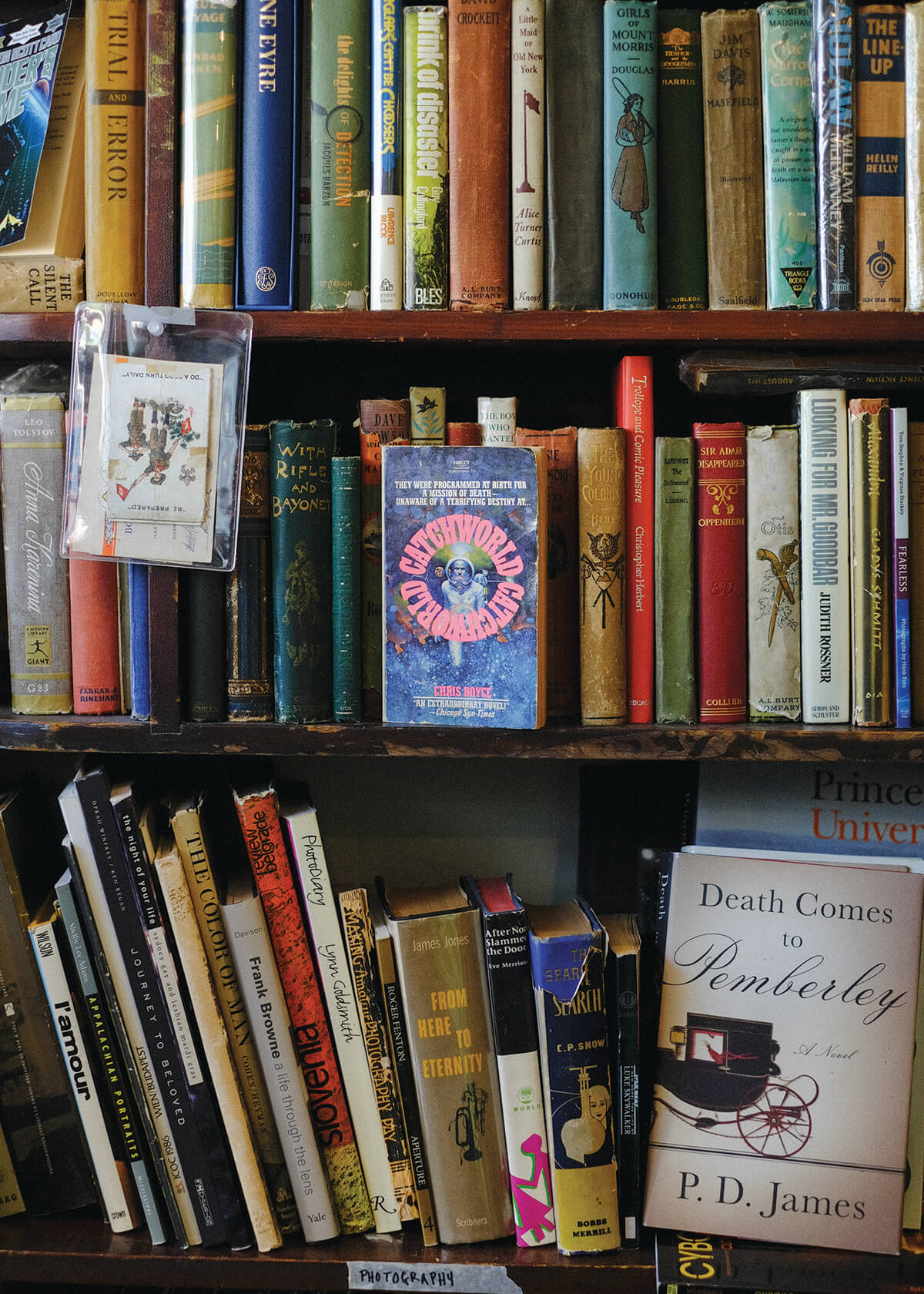

Among the tight shelves at Station North Books, a slow-growing operation which took its initial steps about seven years ago, there seems to be an almost unimaginable range and depth of offerings. There are the literary classics like Henry Fielding, James Baldwin, and Vladimir Nabokov. There are cookbooks, New Age books, self-help books, a section on Tarot, “schlocky beach stuff,” as Sparrow puts it, 200-year-old Bibles, a signed Oliver Sacks, and—a nicely Baltimorean touch—a 1935 Poe’s Tales illustrated by Arthur Rackham.

“That seems less organized than it is,” he says as he points to another wall of titles. “Everything up here is signed. So that Ishiguro is signed.”

He also has Edith Wharton and Gertrude Stein first editions. Sometimes, he intentionally misfiles things just to amuse himself. For example, Ulysses is stocked under “Psych,” he says, “just for giggles.”

There are items besides books, odd bits and pieces that befit Sparrow’s treasure-hunt approach to the job: art by his former MICA students; a cast-iron, corn-cob-shaped muffin tin; taxidermy, including a massive black bear’s head, mounted and hanging up on one wall, shot by his grandfather up in Michigan; more of what he calls “the Luddite things,” like more bins of vinyl and The Hobbit on cassette tape. “Some of those things just arrived when I was chasing books, sometimes in boxed lots,” he says, as well as other oddities, like a fur hat and a dive belt, “just because.”

Then there are the beautiful things, the antique finds that are not, as they might be somewhere else, displayed under glass with massive price tags. “The most special, oldest one is De Cryptographia, which I don’t trot out,” Sparrow says of the first-ever book on cryptography, in Latin and dated to 1517, that he found at a church yard sale some years ago. “They said, ‘Yeah, we tried to sell that last year. Nobody bought it.’ And I said, ‘Well, how much is it?’ I didn’t realize what it was.”

He bought the book for $40—all he had in his pocket at the time—and a basket of honey mushrooms that he’d just foraged. (Sparrow is a first-rate mushroom forager, and supplies Chris Amendola, the James Beard Award-nominated chef of Foraged restaurant, which is a few hundred feet around the corner from the bookshop.) “It’s worth $10,000,” he says of the yard sale find. “Or at least, the last one went at auction for $10,000. I might get more if I give it to Sotheby’s.”

Ned Sparrow—his real name, though it sounds like that of a minor Henry V character—grew up in Grosse Point, Michigan, and came to Baltimore in 1987 right out of Princeton to teach middle school at St. Paul’s School for Boys in Brooklandville. He drove down from New Jersey in his grandfather’s Ford F-250 pickup, a truck with a hunting cabin camper and a compromised muffler. “People would sometimes stop me at intersections,” he says, “and say, ‘Help is on the way.’”

After a few years teaching literature to prep-school kids, he spent a year at the Hopkins Writing Center, getting a master’s under the tutelage of John Barth, Madison Smartt Bell, and Grace Paley. He went back to Princeton for a Ph.D. in English, specializing in continental modernism (“Joyce, Woolf, Fitzgerald, James, Stein”). Then he came back to Baltimore and got a job at MICA, where he stayed for the next 20 years, until two years ago.

“I taught narrative illustration, great books, great short stories, a class called Modern Marrying and Other Bonds,” says Sparrow, who has also taught at Peabody, Goucher, and Stevenson. Between the books he inherited from his grandfather, his parents’ books, and the books he’d acquired over a lifetime spent studying and teaching, Sparrow accumulated a library.

“Around [the year] 2000 my ex said, ‘We’ve got a lot of books here, you should sell some.’” He and his family lived in Lutherville at the time, in an old house that he’d filled with volumes. So he started selling on eBay, then began cataloging the titles and selling on Amazon; he also sold some at the Antiques Emporium in Frederick. “It was my quasi retirement plan,” he says. “Books were everywhere, including in the master bathroom; behind my wife’s perfumes were, like, all of the Modern Library.”

He figures that at the peak of his online sales, he had around 10,000 volumes.

In 2016, Sparrow began selling a few books out of a little coffee shop called Café Sage at 34 E. Lanvale Street—his current location. Not many books, what he characterizes as “excess inventory,” but when the coffee shop closed, Sparrow, who knew the landlord, agreed to take over the lease. His books migrated, and now he says he has between 6,000 and 7,000 in the shop, with maybe another 4,000 in a warehouse “of sorts” in Towson, where he keeps mostly titles from 1970 forward.

He still goes to estate sales, but less frequently, maybe every fourth weekend as opposed to every weekend. Sometimes people send him pictures of books, asking him what they’re worth and if he wants them. If they pique his interest, he hops in his Subaru wagon. “A German Bible from the 1800s, unless it’s signed by Kaiser Wilhelm, I just give them a rough idea [of the price], then show up.” Others bring him volumes. “I take donations, and people do get to a point when they don’t know what to do with them. So they give them to me.” In turn, he will give readers deals, especially if they’re students or teachers.

“I used to just get everything. I was like, well, I need another copy of Henry James’ The Turn of the Screw. And of course I didn’t.”

Sparrow surveys his small, crowded kingdom. A lamp stands on a few volumes, a duck decoy perches on one stack, a teapot on another. He likes to sell books, because that means he’s “putting the book in somebody’s hands,” the ultimate goal. But sometimes what he likes most is the ongoing treasure hunt. Finding that second copy of Henry James, for example, gives him hope that if he sells it, he can find a third.

So, yes, it’s about the hunt, but it’s also about what Sparrow calls the fellowship. This is the group of other booksellers, a group as rarefied as their books, a guild that is both worldwide and as close as a narrow Baltimore street. There are about two dozen independent booksellers in Baltimore these days, including Royal Books, run by Kevin Royal Johnson, which is less than a mile up Charles Street from Station North Books. Viva Books, run by Viva Stowell, is about a mile south, and both booksellers trade books, customers, and camaraderie with Sparrow.

“NED INSISTS THERE IS A VERY CAREFULLY ORGANIZED SHELVING SYSTEM.”

“Ned would come in to deal with customers who wanted to sell collectibles we had already passed on, because we were dealing with volume,” recalls Whitfill, the former Ukazoo Books owner, who still collects books but limits himself to four of his own bookshelves. “He goes for the strange and somewhat macabre, the unusual,” Whitfill says of Sparrow’s proclivities.

Mikita Brottman, an author and MICA professor who teaches courses on Poe, the uncanny, and esoteric thought, comes by Station North Books often. “Sometimes to contribute a box of unwanted volumes, sometimes to see what I can find,” she says. “Sometimes just to hang out with Ned, talk about books, and see what he’s got.”

She’s not interested in collectibles or first editions, Brottman says, only to read, and she likes that Sparrow saves books he knows will interest her—and that he lets her bring her dog in the shop.

“All kinds of interesting people drop by—friends, strangers, writers, poets, teachers, students,” says Brottman. “I like the fact that it’s so chaotic in there. Ned insists there is a very carefully organized shelving system,” though she’s not quite sure about that. “Sometimes it does feel as though everything is on the verge of tipping over and burying Ned in an avalanche of books, but he doesn’t seem worried.”

On a recent day, Sparrow cataloged some of his favorite things: a Robert Burns book bound with green leather, with raised bands and a deckled edge; a 1780 devotional book in Spanish made of vellum (animal skin) and worth, “I don’t know, a couple 100 bucks.” He pulls out an old Bible from an early U.S. printing, circa 1870, the size of a deck of cards, and describes how folks once liked to carry the books in their breast pockets, as they’d been known to stop the occasional bullet.

Sparrow doesn’t sell on Amazon anymore, though he’ll still move a few books on eBay. Mostly he relies on walk-ins and on Instagram, @nedstationnorthbooks, where he posts pictures and details of books, along with Venmo and other contact information. He also likes to post selfies of folks with their just-bought books, another way of working the bookshop fellowship in our virtual age. He has a database, and pages on bookshop.org and biblio.com, though as for the exact contents of his shop, “The stuff around here is in my head.”

Sparrow reflects on his three-room library. “It’s liberating for me to look at a book and say, ‘Yeah, we could look it up [the book’s value]. Or you could give me 20 bucks.’ And it’s kind of Russian roulette, because then you look it up and you say, ‘Look, the cheapest one out there is $400. And I just sold it to you for 20 bucks.’”

And sometimes the transaction works out in his favor; he’s fine either way. Because, as he’ll be the first to tell you, his math is that of an English professor, and what is apparent from the sidewalk is that Sparrow does what he does for the books themselves, and for those who love them.

“There’s nothing like presence,” he says, of both the people and the titles in the shop. “And then coming across something that is next to the thing you’re looking for. It’s not big economics, but the lights are on, there’s that.”