Education & Family

At 100, Mt. Washington Pediatric Hospital is Still Happy on the Hill

One century ago, an enterprising Baltimore woman founded the hospital that most parents don’t know exists—until they need it.

Phyllis C. Meyerhoff was just four years old when her parents took her to a quiet estate in Mt. Washington named Happy Hills Convalescent Home, dropped her off, and drove away. It was 1938 and Meyerhoff, like many children of her era, had been diagnosed with rheumatic fever, first by her pediatrician, then by Helen Taussig, the renowned physician-in-chief of the cardiac clinic at the Harriet Lane Home for Invalid Children at Hopkins. It was Taussig’s recommendation that Meyerhoff go to Happy Hills for what was then known as a rest cure.

“At the time, there were no antibiotics available, which would have corrected [rheumatic fever], so the only known cure for it was complete bed rest,” says Meyerhoff, now 88.

Happy Hills would be Meyerhoff’s home for the next 10 months. To reduce the threat of germs, parent visits were discouraged. Meyerhoff only saw her parents and brother during a few designated hours each Sunday.

“They put me in a crib in a big room with other children,” Meyerhoff recalls. “Of course, there was no television, so they would play the radio—soap operas and, on Saturdays, Let’s Pretend and The Shadow—and we would have a teacher come in during the week to work with us on basic reading and arithmetic.”

Despite the long weeks without her parents and living confined to her bed for most of the day, Meyerhoff remembers the convalescent home as “a loving environment,” where the staff recognized that the children in its care were away from the lives and family they knew. Eventually, Meyerhoff made a complete recovery. As an adult, she learned that her successful recuperation at Happy Hills was made possible by the efforts of a determined young woman, Hortense Kahn Eliasberg, who founded the convalescent home in 1922. One hundred years later, Happy Hills is still serving pediatric patients, and is now known as Mt. Washington Pediatric Hospital (MWPH).

Today, MWPH functions as a modern pediatric hospital, yet for much of its history, it’s been one of Baltimore’s best kept secrets, likely because it helps only the most complex pediatric cases. Patients are mostly referred by pediatricians and often transfer from larger acute hospitals to MWPH to receive additional medical care. It is the place most parents don’t know exists—until they need it.

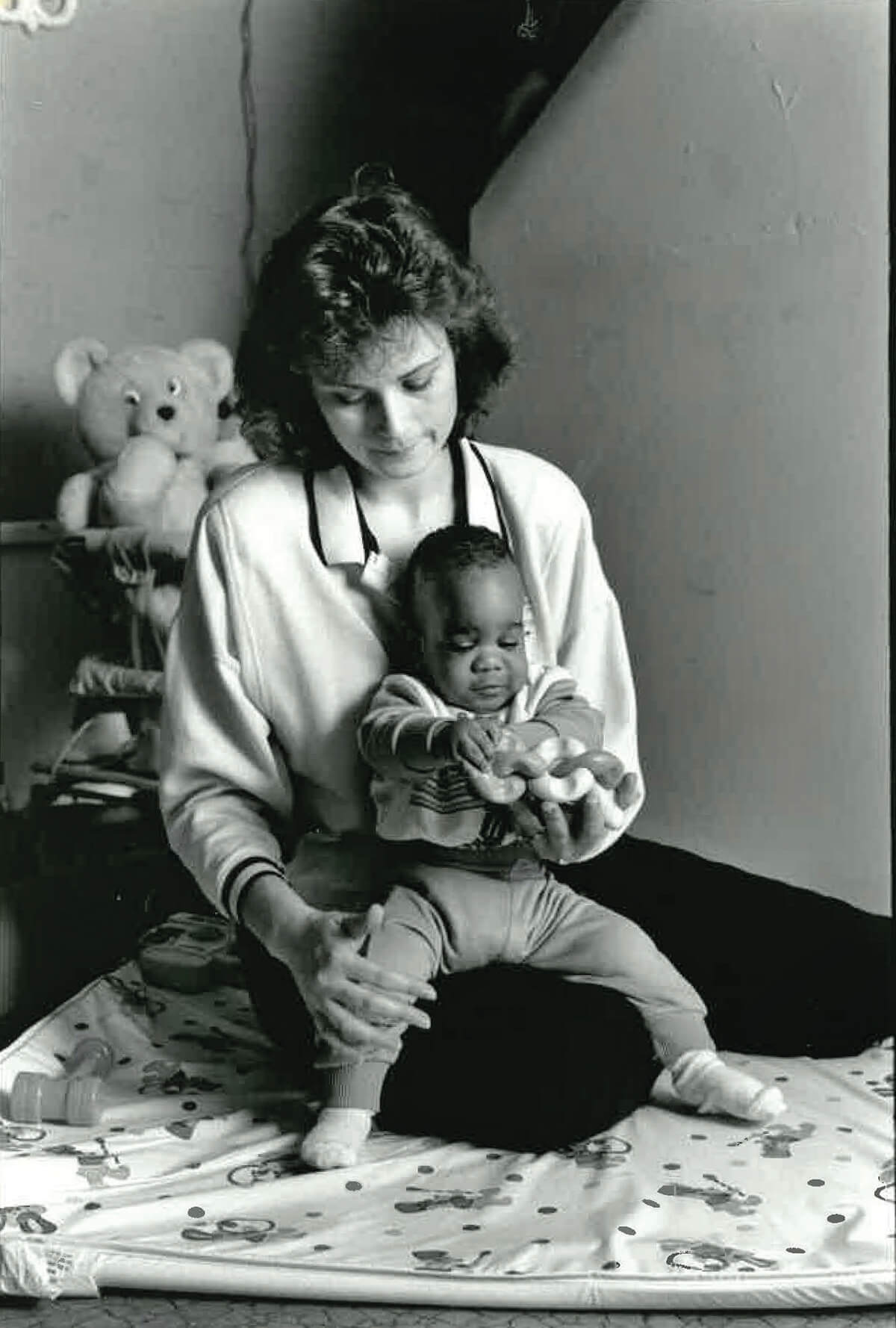

While MWPH has an expansive outpatient reach, much of the inpatient population is comprised of “NICU graduates,” fragile newborns who would never have survived in Eliasberg’s day but who today can safely return home with a little extra time and care. Other inpatients are at MWPH for rehabilitation from traumatic accidents or illness, where the goal is to get each patient to their maximum level of independence. MWPH also has specialty clinics, including those for feeding disorders, sleep medicine, diabetes, and respiratory care.

While MWPH has evolved over the years to care for everything from the effects of lead poisoning to pediatric HIV, in the 1920s it was rheumatic fever that was the leading cause of death in individuals between five and 20 years of age. The disease was caused by untreated group-A strep infections and could significantly, evenly fatally, damage the heart. Childhood in the age before advances like penicillin, vaccines, and Vitamin D in milk was a fraught time, with the looming threat of many health problems for which there were few if any treatments. Even hospitals weren’t as safe as they are now.

“In health care at the turn of the last century, there weren’t private rooms, there were huge wards where children and adults stayed head to toe and when one person sneezed or coughed, it wasn’t long before that went around the whole ward,” says Sheldon Stein, the recently retired president and CEO of MWPH.

But things were often worse at home, and many illnesses and injuries were exacerbated by inadequate care when young patients were released from the hospital.

“When children went home, the conditions were atrocious—poor sanitation, no hot water, infestations of rodents, no healthy meals to eat, in the winter there may have been no heat,” he continues. “Children who left the hospital would soon decline. They needed convalescent care to get stronger to withstand the conditions at home.”

Poor home conditions could be a death sentence for some, especially those living in squalid city poverty. Hortense Kahn Eliasberg, the daughter of Dr. and Mrs. Moses S. Kahn, made remedying this her life’s work. Remarkable for the time, she had the credentials to make it happen. Eliasberg grew up in Reservoir Hill and attended the Girls’ Latin School in Roland Park. She went on to graduate from Goucher College and earned her master’s degree from the Graduate School of Philosophy at Johns Hopkins University in an era when less than 40 percent of college degrees in the nation were awarded to women.

“Her father had some interests similar to this, but I really believe it was her master’s thesis that propelled her in this direction,” says Ann Eliasberg Betten, Eliasberg’s granddaughter and a member of MWPH’s Foundation Board. While researching her thesis, Standards of Care for Convalescent Children, Eliasberg spent time at another convalescent facility in New York, the Campbell Cottages, where Betten explains Eliasberg was moved by what she saw, particularly the discrepancy between those who could afford intermediate recovery care and those who could not.

Eliasberg’s mission was spelled out simply in her thesis: “Convalescent treatment consists essentially of regular hours for sleep, play, work, rest and meals; a well-balanced diet; supervised exercise; and a therapeutic occupation with continuing schooling and some beginning vocational guidance.” Yet Baltimore was one of the few major cities at the time with no convalescent hospital for pediatrics. Eliasberg calculated that at least 200 beds for young people were needed.

Eliasberg didn’t waste any time going after the heaviest hitters in Baltimore to make her home a reality. She brought on board Dr. William Welch, who was then chief physician at Johns Hopkins Hospital School of Hygiene and Public Health and a medical luminary of national and international renown. Though she was just 22 years old, Eliasberg managed to gather other pre-eminent Baltimoreans with deep pockets—no doubt leveraging connections brought on by Welch and her own husband, financier Louis Eliasberg—to fund the project.

In 1922, Happy Hills opened in its first location on Poplar Hill Road in northern Baltimore City. The brick structure (now a private home) could accommodate 20 patients. Notably, children were admitted regardless of their family’s ability to pay. Stein notes that in the ’20s, a stay at Happy Hills was between $1.25 and $1.50 a day. If funds ran short, Eliasberg would press her wealthy friends into donating $25 or so, a sizeable sum in Depression-era dollars.

“To my knowledge, there’s never been a patient turned away because of an inability to pay,” says Stein. Patients stayed as long as necessary, which was often lengthy given the needs of the population. In a report presented to the board of trustees in 1923, the average stay was stated to be just over 10 weeks.

Though less than 10 miles from the center of the city, Happy Hills was a world away from the smog, congestion, and poor sanitation of downtown Baltimore. Here, children could play and rest in the fresh air and eat healthful meals. The lack of visitors meant they weren’t exposed to additional viruses that could deplete their fragile constitutions. The rest cure was so successful, it wasn’t long before Happy Hills had a waiting list. Once again, Eliasberg used her fundraising savvy to help secure the purchase of the estate of George Whitelock on West Rodgers Avenue. Today’s MWPH sits not far from that original location.

In a Baltimore Sun photograph from the formal opening of the new location in 1930, Eliasberg cuts a glamorous figure in a fur-trimmed coat and cloche hat. Yet by all accounts she was humble, choosing only ever to be the secretary of the board of trustees as a way of allowing other important people to have more prominent board seats. Despite years of working at Happy Hills, she never drew a paycheck.

Eliasberg was also indefatigable in her philanthropic outreach. She represented Baltimore at the Maryland League of Women Voters’ conference on internationalism in Washington, D.C., chaired the Women’s Committee of the Baltimore Roundtable of the National Conference on Christians and Jews, and served on the executive committee of the Baltimore Community Chest, just to name a few of her charities.

Yet much like MWPH, until recently Eliasberg’s legacy has been one of the area’s best-kept secrets. Betten says she has learned a lot about her grandmother through the celebrations of MWPH’s 100th anniversary, including the publication of a book co-authored by her uncle, Richard A. Eliasberg, with Meg Fairfax Fielding. Her grandmother died in 1949, at the age of 49 after a long illness, and Betten believes it was too painful for the family to speak of her after that loss.

“She must have been quite energetic and enthusiastic—infectious—to get these people behind her,” says Betten. “How else did a woman who was just 22 years old get the support of Dr. Welch? At 22, I would’ve cowered before such a person.”

As an adult, Phyllis Meyerhoff had an opportunity to meet Eliasberg at one of the Eliasbergs’ annual New Year’s Day open house parties. “She was a very elegant, lovely person,” says Meyerhoff, a benefactor and MWPH honorary trustee (the Phyllis C. Meyerhoff Center for Pediatric and Adolescent Rehabilitation was dedicated in 2021). “I think it saved my life to have a convalescent home to go to,” Meyerhoff continues, “and I was able to tell [Eliasberg] about my experience and how much I appreciated what she had done.”

Eliasberg’s portrait hangs in the main entry of MWPH. If she were alive today, she might recognize the landscape. The current MWPH sits gently on its wooded site, an architectural decision made with intention, as the buildings have always been designed to feel more like a home than a hospital. And MWPH still operates as a home away from home for many patients who need extra care beyond what can be given in a traditional hospital setting.

Dawn Acab’s granddaughter, Hailey Withers, 14, has received care at MWPH since she was three. Withers had an accident at age two that left her paralyzed from the neck down and on a ventilator. Being at MWPH was life-changing for both Acab, who is her granddaughter’s caregiver, and Withers. Previously, Withers’ appointments were spread over many hospitals and physicians; it was exhausting for Acab to handle full-time work, Withers’ care needs, and disparate health care appointments and specialists. At MWPH everything was in one place. The impact on Withers’ health was remarkable.

“Doctors had told us she would be in bed for the rest of her life, that she would never talk or eat,” says Acab. “Once we got to Mt. Washington, I don’t think I ever heard anyone say she wouldn’t be able to do something or we’re going to baby her,” says Acab. “It’s always been ‘Let’s figure out a way for her to do it,’ and, ‘If you fall down, we’ll pick you up and make you better.’”

At MWPH, Withers receives occupational and physical therapy, obtains adaptive equipment, and has access to a psychologist as well as oversight by her physician, Virginia Keane. Withers has gained limited arm movement, enough to feed and dress herself. She recently celebrated a major victory—the removal of her tracheotomy. Her grandmother says that’s a big step toward normalcy for Withers, who is now in ninth grade at Green Street Academy in Baltimore City, where she’s in conversation with the basketball coach about possibly becoming the equipment manager.

“It’s not good that children are sick or suffering trauma,” says Stein. “We all want hospitals like Mt. Washington to go away, but since the need hasn’t gone away, I think Hortense would be proud that the mission continues.”

Stein started work at MWPH in 1995 and became president and CEO in 2002. In some ways, the anniversary year is also an homage to his 20-plus-year tenure, which concluded when he retired in November of this year. Stein has witnessed massive changes in health care that have affected MWPH, most notably the expansion of out-patient medicine.

![1969-70 performance[1]](https://www.baltimoremagazine.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/11/1969-70-performance1.jpg)

Where Eliasberg was advocating for children to spend weeks and even months in recuperative care, modern medicine relies heavily on outpatient clinics. MWPH is projected to conduct approximately 60,000 outpatient visits in fiscal year 2023. The hospital has expanded its footprint with locations in Prince George’s and Harford counties. It was also during Stein’s tenure that MWPH obtained its unique, dual ownership. In 2006 MWPH became a joint affiliate of Johns Hopkins Medicine and the University of Maryland Medical System.

Behavioral health needs have exploded during Stein’s tenure. MWPH helps children on the autism spectrum and those with learning differences, but also, and most disheartening for Stein, children dealing with the effects of trauma like gun violence. “When I started, we had nine psychologists and now we have almost 40,” he says. “If I could hire 40 more I would, and their schedules would all be booked.”

The name may have changed, but MWPH is still a happy place on a hill. Its story and history mirror the story and history of pediatric health care, from an era before antibiotics, Medicaid, and proper sanitation, all the way through to today’s post-COVID-19 needs.

“In the next 100 years we’ll continue to grow and survive,” says Stein. “We’ve re-engineered decade after decade to take care of children. What used to be rheumatic fever and lead poisoning and HIV, today is prematurity, diabetes, and trauma. The hospital has always been nimble and able to redefine itself as children’s needs change.”

Eliasberg outlined in her thesis how she believed standardized convalescent care could stop the creation of “the half-cured,” those “patients who flounder aimlessly about clinics for weeks and months endeavoring to regain health.”

While today’s medical complexities exceed what would have been seen in her day, Eliasberg’s call to action is as sound today as it was a century ago.

“It is not by a charm of magic nor by some act of sleight-of-hand, or the course of nature,” she wrote, “but by definite and intelligent care that a patient is able speedily to return to sound health after illness.”