Arts & Culture

Arena Players, The Oldest Black Theater in America, Continues to Set the Stage at 70

When the theater debuted during an era of civil rights resistance in 1953, it was uncertain if it would survive a single season. Now, it's embarking on its seventh decade.

On a Monday afternoon, it’s difficult to find Donald Owens. With a yellow highlighter and black pen tucked into his shirt pocket, he’s rarely in his office, instead shuffling throughout the Arena Players building, meeting with members of his cast and crew or planning out the theater’s upcoming season schedule. It’s not uncommon for the artistic director to work until close to midnight.

It’s been more than 50 years for Owens, pictured above, but he still remembers the day he first learned about this theater, now located on McCulloh Street in West Baltimore. He was a student at Coppin State College when a professor named Samuel Wilson Jr. took him under his wing. Wilson had heard that the young man was an aspiring thespian and he thought he might like to join his community theater troupe.

“At first, I acted, and then I would direct,” says Owens, looking back over the decades, “and then I would teach.”

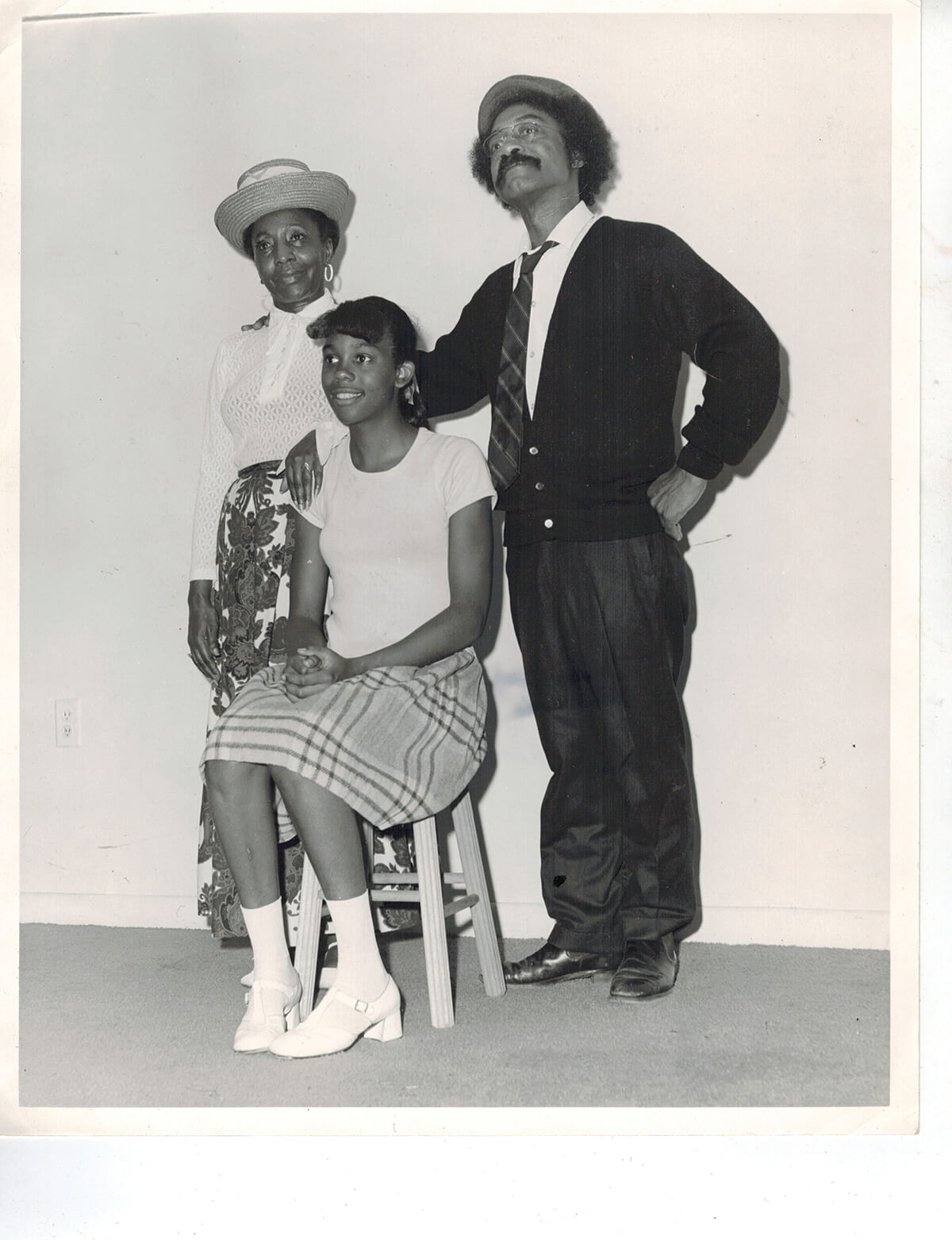

It was the 1970s, and after a nomadic first decade, the Arena Players had finally found a permanent home. During this time, the cast and crew grew rapidly, and before long, word of mouth had spread through the city and neighboring counties, with Black spectators flocking to the box office. It was normal to sell out their 300 tickets on any given night.

“The audience was huge then,” says Owens. “They had no place else to go.”

Arena Players will begin its 70th season this September, cementing its status as the nation’s oldest continuously operating Black theater company. But when it debuted in Baltimore in 1953, it was uncertain if it would survive a single season.

Even with free admission, the first few shows were more cast members than ticket-holders. Back then, an ensemble of seven to 12 actors, from local college students to community residents, would be lucky to perform for an audience of four. At the time, this small group of Black actors couldn’t watch—let alone participate in—performances at big-name theater houses, be it on Broadway or in Baltimore.

“Unless you were playing a maid or a butler, there was no need for you in white theaters,” says Owens, referring to the Jim Crow prejudices that kept cultural institutions racially segregated well into the 20th century.

But this was also an era of civil rights resistance. From fine art to photography, the Black community was leading a wave of artistic movements across the country, fighting back by creating their own representation, with community theaters emerging as creative refuges in cities like New York, Chicago, and Washington, D.C.

“Theater has always been a political movement,” says Owens, noting that some of the earliest plays, from Greek tragedies to Shakespeare, dealt with some form of protest.

In Harlem, the pioneering American Negro Theatre opened in 1940, followed by the Black Arts Repertory Theatre and School in 1965 and the New Federal Theatre in 1970. Black community theaters were places where Black thespians could write, perform, and direct works by Black artists, including luminaries like Lorraine Hansberry, Ossie Davis, and James Baldwin.

“Everybody just assumed there were no Black playwrights,” says Owens. “Black playwrights did not begin with August Wilson [in the 1980s]. Black playwrights have been around for centuries.”

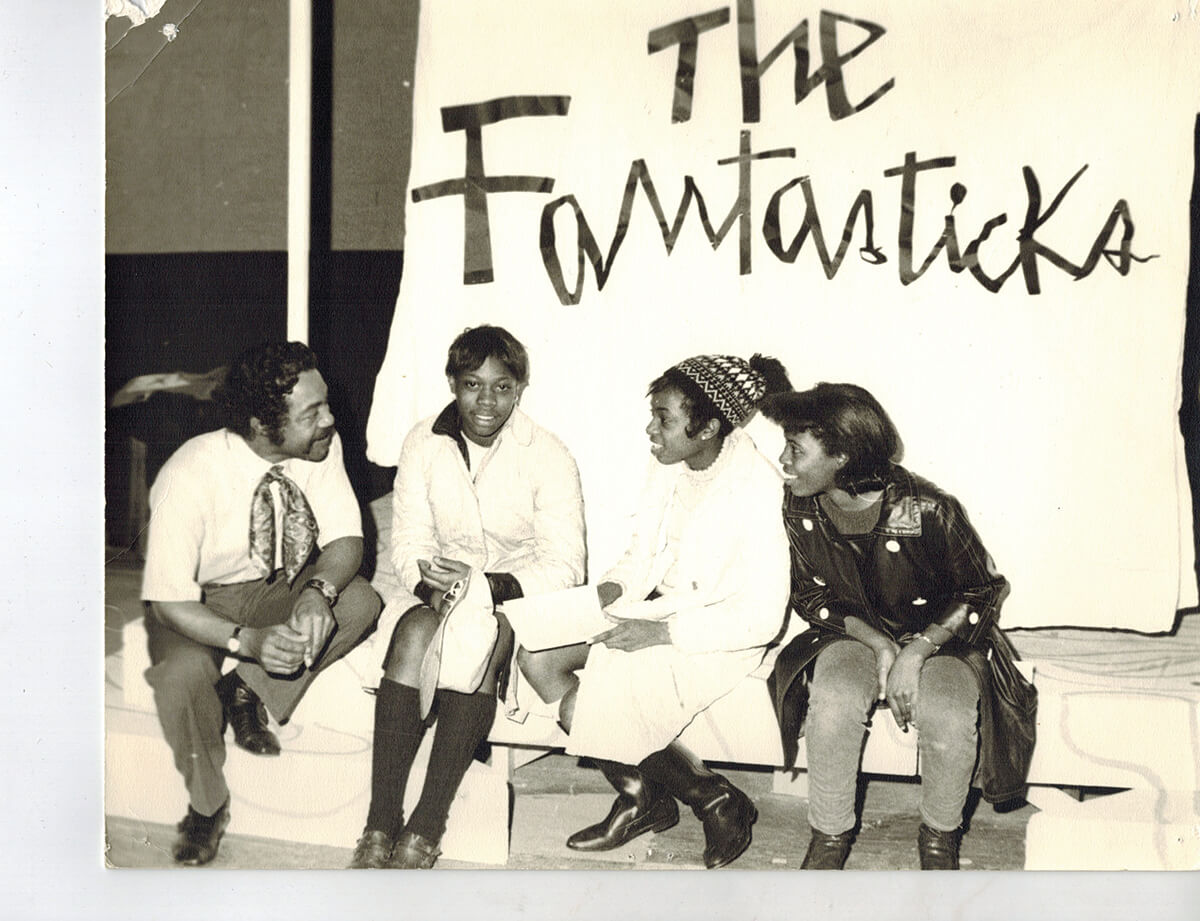

Meanwhile, historically Black colleges became another respite for Black theater. In Baltimore, Arena Players got its start on campus at what is now Coppin State University in 1953. Its theater-in-the-round playhouse soon became a hub where aspiring actors and other community members—from lawyers, doctors, and teachers to housewives and retirees—could regularly partake in the theatrical world.

At this time in Baltimore, venues for the Black arts scene were few and far between, despite a large Black population. Pennsylvania Avenue was one of the few hubs, with the Royal Theatre being a premiere venue for iconic musicians like Ella Fitzgerald and Louis Armstrong. Further along the avenue, other spots like the Sphinx Club, Club Casino, and Club Tijuana hosted the likes of Billie Holiday and Miles Davis.

And though it took a while to find an audience, the word eventually got out about Arena Players, with coverage of its early seasons appearing increasingly in The Sun. The company’s first production was the one-act Hello Out There! by Armenian-American playwright William Saroyan, and within a few years, their performance of the musical Simply Heavenly brought its author, Langston Hughes, to the front row.

Their repertoire ranged from one-act plays to full-scale productions across a variety of genres, such as comedy, drama, and mystery, which also included famous works by white playwrights, such as Alfred Hitchcock, Arthur Miller, Edna St. Vincent Millay, and Tennessee Williams. Similarly, audiences were predominantly Black, but there were white attendees, too, and groups like sororities, fraternities, church congregations, and other social clubs regularly sponsored private viewings. Tickets hovered around $1, and at times they sold out.

Still, the Black theater company was a small operation. Troupe members had to bring in furniture from their own homes to use as props, and while Coppin was their launchpad, throughout that first decade, Arena Players moved between multiple venues. They put on shows at the Great Hall Theater of St. Mary’s Church in Walbrook, at Morgan State University’s Carl J. Murphy Auditorium, and at the YMCA in Madison Park, where crew members would build intricate sets on Friday, just to tear the whole thing down by Sunday night.

“Though the beginning was not easy, the sense of commitment was great, and individuals gave liberally of their time and resources to bring their dreams to reality,” wrote then-artistic director Ed Terry in a 50th anniversary booklet in 2003. “Through the first decade, the names of the Players were well known, and the actors constituted a kind of resident company as they wandered from one venue to another in search of a permanent home.”

They finally moved to their McCulloh Street home in 1969—a curved brick building in the Seton Hill neighborhood between Mt. Vernon and West Baltimore. And what was once a coffin warehouse for a local mortuary became the permanent home of a historic Black theater.

Two silver plaques greet you when you step through the front door of Arena Players. One is dedicated to Irvin Turner, who founded Arena’s “Youtheatre” program in 1974. The other is for Sam Wilson, Owens’ former mentor, who died in 1996. On his, there’s a quote: “I do not believe anyone is supposed to leave this earth having held on to his or her talent. You’ve got to share it. You’ve got to hand it to somebody else.”

Today, Arena Players has 45 cast and crew, with performers ranging in age from toddlers to octogenarians. For about 10 years in the 1980s, ticket sales and grants for the youth theater were what kept Arena Players open and operating—and some of those performers are still with the troupe today.

In her own way, Catherine Orange is an Arena Players lifer. The youth program director was also encouraged by Wilson to join the troupe while a Coppin State student in 1972, but by that time, she already knew the theater well, having visited since childhood with her grandmother. Over the years, she’s had her hand in everything from hair-and-makeup to stage managing, and eventually she got her own children and then grandchildren involved. Her son, Rodney, was the theater’s managing director until his death in 2019. Her grandson, Dana, now a professional performer, got his start at Arena Players when he was just four years old.

“For kids who want to grow and to develop their creativity, this is a great place to start,” says Orange, noting that some young troupe members continued their interest at the Baltimore School for the Arts and Peabody Institute.

In fact, Arena Players has many notable alumni, including those who have worked on Broadway or in the film industry. Actress Tracie Thoms, who starred in Rent and The Devil Wears Prada, got her start on the Arena Players stage. And Tony Award-winning actor, singer, dancer, and director André De Shields has often praised Arena Players for being one of the few places where he could explore the arts as a young boy growing up in Baltimore.

Owens is a D.C. native but started acting at age six. Now at 76, he’s the glue that holds the theater together, responsible for handling everything from the building’s maintenance to the season’s lineup. This past November, three of the four walls in his office were covered in dry-erase calendars marked with the troupe’s performance dates through 2023.

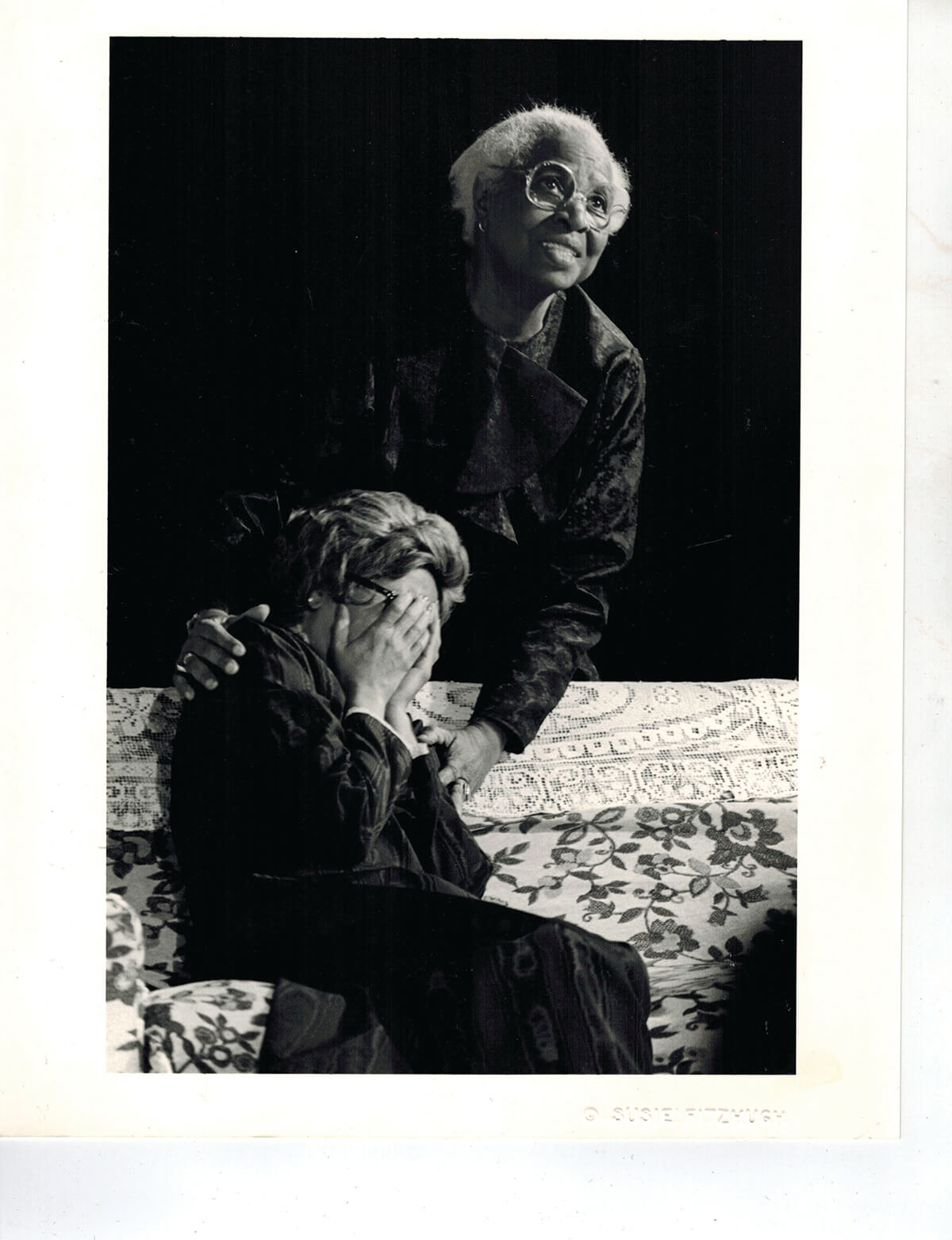

When selecting which plays to perform, Owens tries to prioritize what he calls “entertainment teaching,” rooted in a founding philosophy of bringing underrepresented works with historical significance to the forefront. To that end, the players recently mounted a production of The Face of Emmett Till, the true story chronicling of the life, death, and aftermath of a 14-year-old Black boy who was murdered by two white men for allegedly whistling at a white woman in 1955 Mississippi. In many ways, says Owens, this follows the great tradition of Black performing arts venues.

“Black theaters allowed Black people to perform, they allowed them to write and direct, and they allowed their work to be seen,” he says, with other now-classic Black works such as The Wiz fantasy musical and the tragic for colored girls who have considered suicide/when the rainbow is enuf having premiered here over the years. “That was really important.”

It meant their stories would be told.

For Arena Players, it’s a legacy that’s made an impact. Alongside actor portraits and framed newspaper clippings, the theater’s walls are decorated with official recognition. In 2018, a signed letter from late Congressman Elijah E. Cummings called the theater a “lasting cultural icon.” In more recent years, they’ve also caught the attention of historians, with Morgan State University currently working with the theater’s archives in hopes of creating a future digital exhibition.

“The Arena Players’ archives demonstrate African-American agency [in] Baltimore during the early civil rights era,” says Morgan State archivist Ida E. Jones. “This community space provided room to nurture positive Black images, cultivate innate talent, and expose Black Baltimore to the mechanics of theater work.”

That sort of preservation project is vital for a nonprofit theater with limited staff and resources. Over the years, they have experienced their fair share of financial ups and downs, and today, they primarily rely on grants and community donations to stay afloat.

“We’re beginning to see some daylight,” says board chair Larry Cook, a West Baltimore native and former state senator who has been involved with the theater for over two decades, with much of his efforts focused on lobbying support from city and state government. “It’s been a task, but we’ve stayed persistent.”

Cook points to the forthcoming renovations to the building, which hasn’t had any major upgrades since the ’70s, with the third floor, currently used as a rehearsal space, being transformed into a black-box theater, in order to have multiple shows taking place at once. Other plans include modernizing the light fixtures and seating to improve the audience’s experience and accessibility.

The Arena Players audience looks different now than when it first started. While still majority Black, the crowd is often representative of a variety of races, reflective of the Baltimore theater scene’s diversification, as mainstream venues like Center Stage and Everyman Theatre cultivate more inclusive casts and repertoires.

This could explain why they’re not seeing nearly as many full houses these days, but the theater continues to put on up to seven shows per season. This year’s first performance will not premiere until September, but right before Christmas, they were gearing up for a performance of Langston Hughes’ Black Nativity.

For Owens, though, even in changing times, the Arena Players mission is just as important as it ever was—some 70 years and counting—and will continue to be in the future.

“The energy here is powerful, even to this day,” he says. “It has such a history, and it has such a dedicated set of people, and that keeps the fire burning.”