Food & Drink

Let There Be Garlic Bread

With plenty of booze and butter, Peter’s Inn is quintessential Baltimore.

Karin Tiffany is embracing change these days. At 57, she’s seen plenty of it, with more than half of her life spent on the quiet, tree-lined, 500 block of South Ann Street near Eastern Avenue at Peter’s Inn.

Inside her beloved rowhome restaurant, the taxidermied marlin and neon “cocktails” sign still hang, as they have for decades, but there’s also a new tin ceiling, shiny glass chandeliers, and a fresh coat of paint on the cleaned-up walls, with much of the iconic bric-a-brac that once graced them—string lights, folk art, knickknacks, even the occasional Ouija board—never replaced after a cigarette fire engulfed the place in 2017.

“I’m a little hoard-y,” admits Karin, recalling her kitschy collection with an ever-so-slight Bawlmer accent. “It’s fun to watch yourself grow up—I was like, ‘Goodbye! Good riddance!’ I don’t need everything that I’ve liked my entire life out here collecting dust.”

Outside, her neighborhood has evolved, too: Long gone are all the little Polish ladies who used to live up and down the block, along with the freight train that ran along Aliceanna Street, and the slew of vintage stores, junk shops, and dive bars that catered to the eclectic, rough-around-the-edges crossroads that was old Fells Point.

“There were the two ex-cops who had that jewelry store by E.J. Bugs Saloon,” recalls her husband, Bud, 61, dressed in a black chef’s shirt, his gray goatee dyed an azure shade of blue, as the couple racks their brains about other lifetimes from the back dining room.

“Look at your memory!” cracks Karin, her bracelets jangling above fading tattoos, including one small heart on her left wrist, filled in with the black-and-yellow flag of Baltimore City. “When we got married, I said nobody would have a playdate here. Whereas nowadays, a mother will be sitting at the bar with her baby, drinking wine, like no big deal. And I’m into it.”

Still, then and now, Peter’s Inn has never been a puritan’s playground—even if the owner finds herself cussing less, and fewer and fewer customers pull up on Harley-Davidsons—and that’s part of its magic.

Baltimore was once home to a motley crew of epicurean eccentrics—Martick’s, Haussner’s, Gampy’s, the Cultured Pearl—with each bottling the city’s underdog spirit in their own idiosyncratic, irreverent, oftentimes beatnik way. But the baby-doll décor, snakeskin wallpaper, and surly barmaids of yesteryear have since given way to a high-end, highly sanitized homogeny of dining establishments, and so it’s no surprise that, for many residents, Peter’s is now a respite.

Here, the pours are potent, the butter is liberally lacquered, and the bathroom art includes the occasional naked woman, all adding to its tongue-in-cheek charm. There’s little room for fools or fuss—unless the latter involves Karin fretting over the ideal garnish. And it doesn’t hurt that the food is good, even great, too.

At the end of an era, Peter’s is arguably the most bona fide Baltimore restaurant, if not the last one left in town.

Though don’t take our word for it:

“Peter’s Inn is my favorite restaurant in Baltimore,” says local filmmaker John Waters, who was treated to a cake featuring his own likeness during his last birthday dinner here, special ordered by Karin from Herman’s Bakery in Dundalk. “It is shabbily upscale, foodie elitist in a bohemian way, and totally unpretentious, yet has an attitude.”

As it always has.

When Peter’s Inn opened in 1977, it was, for all intents and purposes, a biker bar, helmed by its namesake owner, the late Peter Denzer—a well-to-do D.C. native turned gravedigger, locomotive repairman, cab driver, and newspaperman who rode a Triumph, loved Ernest Hemingway, and made a cameo in Desperate Living, the 1977 dark comedy by Waters, who was a regular back then, too.

“Peter’s Inn was easy to spot,” wrote The Sun in 1979, detailing its then-Formstone façade and glass-brick windows. “The big black motorcycle parked in front helped; so did the loud, cheerful voices spilling out the door.”

At the time, there were no white tablecloths or martini glasses, but Denzer kept hydrangeas on the small tables, a jukebox spinning country tunes, and business cards that declared this place to be “a no-B.S. drinking bar,” one that was treasured by a sundry crowd—Sparrows Point shift workers, artists, nurses, cops, including mounted police, whose horses, tied up outside, would stick their heads in through the open windows.

The Tiffanys arrived in the early 1990s. Growing up between Joppatowne and Bolton Hill, Karin learned to cook in the Coast Guard’s culinary school before eventually landing back in her hometown, bartending around Fells Point—the stomping grounds of her rebellious teen years (she had her first drink at Bertha’s at age 13).

She met Bud, a bass player and land surveyor from Pennsylvania, on the Broadway Square, where he played impromptu games of cricket, and from which the couple would scramble to watering holes like John Stevens and 1919. But getting a job at Peter’s was not as simple as inquiring with the owner—instead, she would have to arm-wrestle his wife.

“This is the honest truth,” declares Karin today, dressed in a white polka-dot blouse, bolo-tie necklace, and thick-rimmed glasses, her style somewhere between retro feminine and art-school punk. “Needless to say, I won.”

At that point, the bar had already started to become a restaurant. A galley kitchen was installed in the back for meals on weekends, and Sun critic Elizabeth Large hailed its menu “home-cooked food with a little pizzazz”—a cuisine that Karin would elevate upon her takeover. When she got engaged to Bud in 1995, her boss presented the young couple with a proposition.

“Pete was like, ‘You’re getting married, you should buy a bar,’” says Bud. “And we did—the day after.”

With Denzer off to retirement in West Virginia, the Tiffanys, then in their late 20s and early 30s, bought the two-story building and moved into the upstairs apartment. But they spent most of their waking hours on the first floor, beyond the brick steps, through the lipstick-red front door.

From the start, they did it all—making the food, scrubbing the floors, tending the bar after Bud got home from his day job. Over time, they added their own flair, taking inspiration from other restaurants and reviews from The New York Times to Bon Appétit. Better wine. Soft lighting. A New American menu that somehow straddled the line between down-home comfort food, haute fine-dining, and your quirky aunt’s mystery Jell-O salad.

“I don’t have ethnicity, we’re Mayflower trash, so the world is my oyster,” says Karin matter-of-factly, her food drawing on European techniques and international touches. “I’m not committed to what my mom made—that was boiled eggs and Salisbury steak, man. This is all just instinct.”

“IT IS SHABBILY UPSCALE, FOODIE ELITIST IN A BOHEMIAN WAY, AND TOTALLY UNPRETENTIOUS, YET HAS AN ATTITUDE.”

In truth, the menu is an embodiment of its creator—no frills, yet properly festive, and always delightfully unconventional.

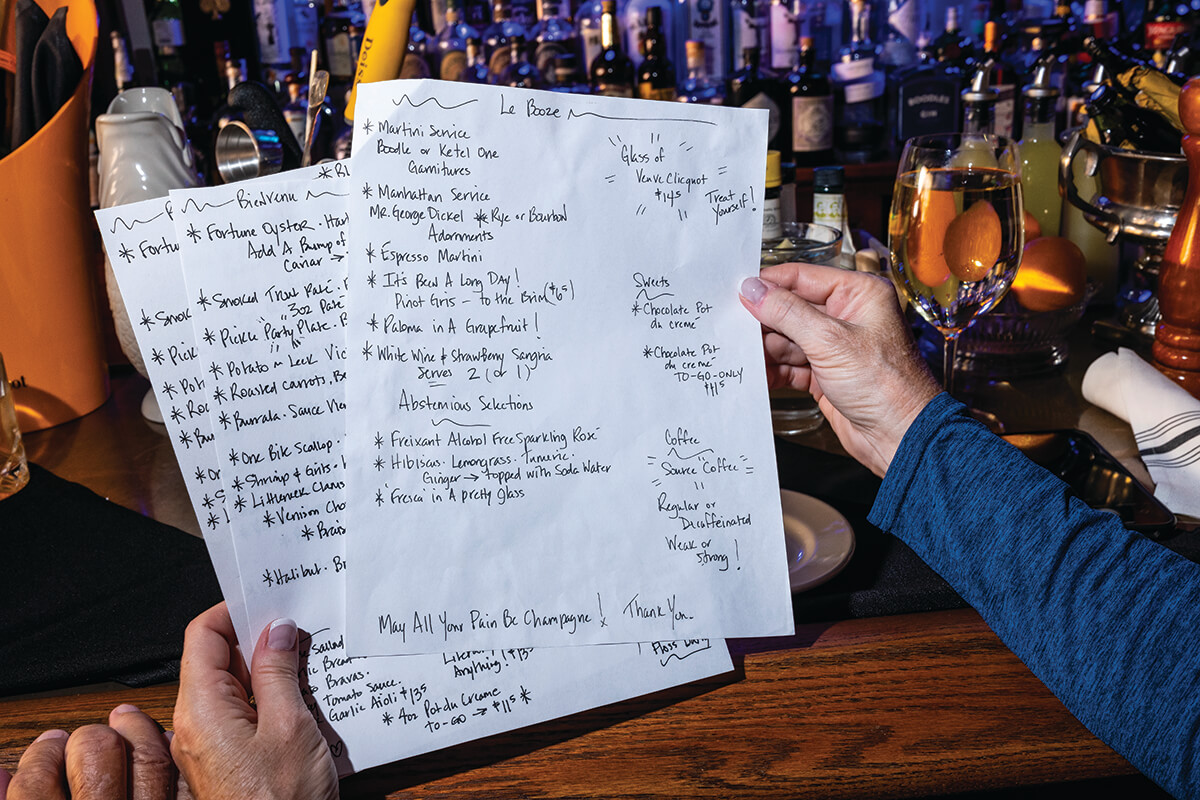

Take, for instance, one of her weekly hand-written menus from this past June—number 1,308—which encouraged diners to not only “be well” and “tip well” but “floss daily,” too. A “bump of caviar” could be ordered alongside fresh oysters on the half-shell, accompanied by mini bottles of Tabasco. There was also chicken liver pâtè in a crystal jar and Low Country shrimp and grits on blue-and-white china. Every meal must begin with the signature house salad and, of course, the garlic bread—a thick Italian slice topped with an almost indecent slather of alliums, herbs, and Gorgonzola that is reason enough to visit. Meanwhile, the long-loved filet mignon, topped with “100% pure butter,” could be a final supper.

“I don’t eat steak anymore, but if I’m going to Peter’s, I will absolutely order one there,” says Richard Gorelick, former food critic for the City Paper and Sun, who once likened dining here to that scene in another Waters film, 1998’s Pecker, where actress Christina Ricci steps off a bus from New York City and kisses the concrete streets of Baltimore. “I don’t want to say that the place is perfect, because that’s a liability, but it always pleases me so much.”

In fact, from every angle, it’s a beautiful chaos, and a wide-ranging congregation comes to be a part of it: “Old people, young people, Black people, white people, Hons, Roland Park ladies, Orthodox Jews, artists,” as Karin once rattled off to us, noting that Sen. Barbara Mikulski likes the back table beneath the oil painting of Karin’s fifth-great-grandfather. “Peter’s is a great equalizer.”

Of course, the “Le Booze” list doesn’t hurt, either. It’s equipped with both martini and Manhattan service—which arrive on a silver platter like some baroque still life, with a sidecar that equals a second drink—as well as a scribbled note wishing that “all your pain be Champagne!” There is also Fresca “in a pretty glass,” and for dessert, French-press pots of coffee to sip with Bud’s decadent pots de crème. Always, a holy grail of Underberg digestifs sits on the bar for the hospitality industry, who usually roll in late-night.

“Peter’s is unabashedly an expression of Karin and Bud’s joie de vivre,” says restaurateur Lane Harlan of Clavel, Fadensonnen, and The Coral Wig, who has dined here for over a decade. “They are remarkable people who have committed themselves to the long haul of hosting. May they continue to sing their song and always bet high on butter and booze.”

Indeed, there is an old-school hospitality instilled into every floorboard of Peter’s Inn, even if it comes with a side of sass. In the past, Karin was known to chastise customers for, say, salting their food before they tasted it, aka “the smartass shit I used to do.”

At first glance, the restaurant can come across as a simple dive bar, and in the most endearing of ways, it is, still encouraging just enough debauchery until last call at 1 a.m., at times devolving into something more bacchanalian, with the bar growing louder and lewder as the hours wane.

But if you look closely, the finer details come into focus. For starters, there are no iPads, no QR codes, no online platforms for reservations—to make one, diners must email Karin directly, which she checks on her phone regularly between the whistles of her catcall ringtone, liking the ability to squeeze a couple in last-minute or rearrange the room for large parties.

“Because we have no TVs, there used to be a bunch of old-timers who would come in with Sun papers under their arms, and they’d sit there and read the sports section and argue over a few beers before moving down the street,” says Bud. “I think the only time we put one up was once or twice for the Preakness or when the Orioles went to the series.”

And there is a level of refinement, even as The Clash and Dire Straits and David Bowie jangle out of the stereo: the towers of fresh-cut fruit, the folded placemats, the pepper grinders on every table. “I’m kind of a sociopath,” says Karin. “I’ll notice if your ketchup bottle is dirty.”

“IT IS UNABASHEDLY AN EXPRESSION OF KARIN AND BUD’S JOIE DE VIVRE.”

In the kitchen, that ethos shows up in her ingredients, too. There are no false buzzwords like “hyper-local” or “sustainable” here; instead, the goal is quality—for the most part, proteins are sourced from Fells Point Wholesale Meats, seafood hails from Philadelphia’s Samuels & Son, produce gets dropped off by the regional Chesapeake Farm to Table collective, and loaves of bread for that vampire-defying appetizer are picked up at Maranto Bakery on Pearl Street. Each dish contains a dash of whimsy, and Karin takes great pride in their unexpected yet elegant simplicity.

“The look on some people’s faces, when they come in and are clearly like, ‘Oh, no…what is this place, what are we doing here?’” she says. “I love surprising them. To see people enjoying this food—particularly the really bitchy ones—it still astounds me.”

When composing their weekly menu, she and Bud tweak ingredients here and there, whispering to one another, What do you think, what do you think?

“We collaborate all the time,” says Karin, calling him her official taste-tester. “She’s the taskmaster,” he adds. “And because of that, and there being the two of us, there’s consistency.”

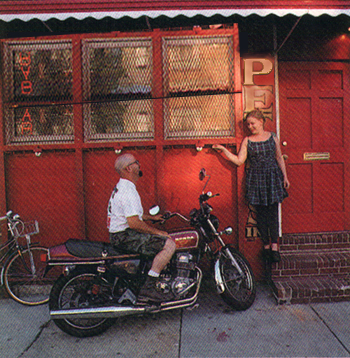

Both spouses agree that one balances out the other—him being the cool calm to her capriciousness, and there’s a clear camaraderie and quiet affection coursing between the two. A photograph from the early days captures it well, with the young couple exchanging a smile outside of their little red restaurant. And then there’s the cover of this magazine’s 2000 “Best Restaurants” issue, when they posed as the straight-faced farmers in “American Gothic”—just one of the many times that local press pampered them with praise.

“I mean, we do fight,” says Karin, even occasionally in front of the small staff. “We’ve employed a million people here over the years, and during that time, we’ve had to say, ‘We’re not your parents, don’t get upset, just move along.’ But I barely raise my voice anymore. A few weeks ago, I screamed at one of the cats and they were all taken aback. Though she’s a Bengal, and an asshole, so it was appropriate.”

Just before service on that June afternoon, her six “co-workers,” as she calls them, were readying the dining room for dinner, which now takes place Thursday through Saturday, compared to its former five days a week. On Sundays, Karin starts brewing the next week’s menu, then she and Bud go out day-drinking, often listening to live music around the neighborhood before doing their best to make it in bed by 9 p.m. On Mondays, they clean and tend to their to-do list, and on Tuesdays and Wednesdays, deliveries arrive, then prep begins.

Kate Bennett maintains the bar, topping off drinks when guests aren’t looking, while chef de cuisine Dale Fields swings in and out of the dark-blue back door, adorned with an Alice in Wonderland-like, giant’s- sized spoon, beneath a glowing sign that deems the “Kitchen Open.” Bud usually joins him, firing proteins over the gas range between running plates and snapping pictures for the Instagram. And throughout it all, Karin serves as supervisor, though she rarely works the line these days.

“Not unless I can’t avoid it,” she says, choosing instead to hold court on the sidewalk patio this soft, warm evening.

At this point, Karin is culinary royalty here in Baltimore, and after three decades on the local food scene—aka forever—she deserves a moment to just preside. Particularly after the fire, which the restaurant only survived thanks to the community raising $22,000 via a GoFundMe. And the pandemic, during which they pivoted to carryout for the first, and only, time. And then one particularly distressing run-in with the Baltimore City Health Department last fall, when inspectors barged in on a Friday night as a packed house devoured Caesar-style deviled eggs and tomahawk steaks. They would ultimately have to close their doors to upgrade the refrigeration.

“Over the course of a lifetime, so many things happen, and the stuff that used to piss me off just doesn’t bother me anymore,” says Karin. “Besides, I’m on Lexapro. It should be in the drinking water.”

“THERE IS AN OLD-SCHOOL HOSPITALITY INSTILLED INTO EVERY FLOORBOARD OF PETER’S INN, EVEN IF IT COMES WITH A SIDE OF SASS.”

At 5 p.m., both loyal habitués and wide-eyed newcomers begin to amble in through the open door. There is a lone twenty-something walk-in at the end of the bar, a pair of blue-haired ladies pulled up to a nearby two-top, and a gaggle of gussied-up Irishmen who stumble out of the back room, seemingly in celebration mode—to name a few.

Whatever their reasons for coming, it is certain that they each have made this pilgrimage to experience the je ne sais quoi of Peter’s Inn.

And whether they know it or not, as the lights dim and the drinks flow, they can linger in a disappearing version of Baltimore, a place where duckpin bowling alleys, VFW halls, and working-class wharves used to flourish. Most of those have since shuttered, replaced by fancy restaurants, five-star hotels, and modern apartment buildings—but for a few hours, that old torch can burn just a little bit longer here. And then they can grab an after-dinner fireball candy on their way out the door, as they stumble into the night.

Karin doesn’t have time for the nostalgia, though. She likes all the dogs that now live in the neighborhood, as well as her street’s new permit parking. And anyway, there is a restaurant to run, with no plans for retirement anytime soon.

“We don’t have an exit strategy,” says Karin, calling Peter’s their “own little weird world.” “Life goes on, and on, and on, and we’ll still be here.”

“After all, we live upstairs,” says Bud. “Instead of home sweet home, it’s home sweet bar.”