Arts & Culture

Baltimore Is In the Midst of a Black Arts Renaissance

Baltimore might be becoming the next epicenter for Black American art. It needs support to last.

Growing up in Baltimore, I was surrounded by Black elders who schooled me about Black history. My grandfather Frank, for instance, would scoop me every Sunday on the way to church. Blasting music from The Delfonics or Funkadelic, he would tell stories about the city in the 1970s, like nights at the legendary Odell’s Nightclub, where you could hear the latest disco tracks and party in harmony with people of all identities. To him, and in turn to me, Baltimore was a Black cultural oasis.

Beyond this oral tradition, I was also literally surrounded by reminders of Black ingenuity. My elementary school in Seton Hill was named after the Black British composer Samuel Coleridge-Taylor. I went to Booker T. Washington Middle, just like Supreme Court Justice Thurgood Marshall. Every morning, I walked past the Billie Holiday statue on Pennsylvania Avenue, a street that housed the famous Royal Theatre and, for the first half of the 20th century, was the happening block for Black entertainers (including the blues singer herself, who once lived near Patterson Park). And as a pre-teen, I made trips to the Eubie Blake Center, named after the celebrated pianist who grew up near Oldtown.

All of this was in my ethos, in my air, reverberating throughout the frequency of my youth. Yet throughout my childhood, and to this day, Black Baltimore has been burdened by so many negative narratives. Years of battling gun violence and drugs have tainted outsiders’ perceptions of this city, and impacted those of us who live here, too, especially young Black people. Many internalize this as a place of despair that will never amount to anything.

I was fortunate to be given a window into another story: that Baltimore could produce iconic Black artists who made profound contributions to the American story. And that the city was full of folks who were doing so in this very moment.

During my lifetime, there have always been ebbs and flows to Baltimore’s art scenes. One minute they’re booming, catching national attention, but that never seems to stick. Meanwhile, many artists are left to believe that they need to leave the city in order to “make it.”

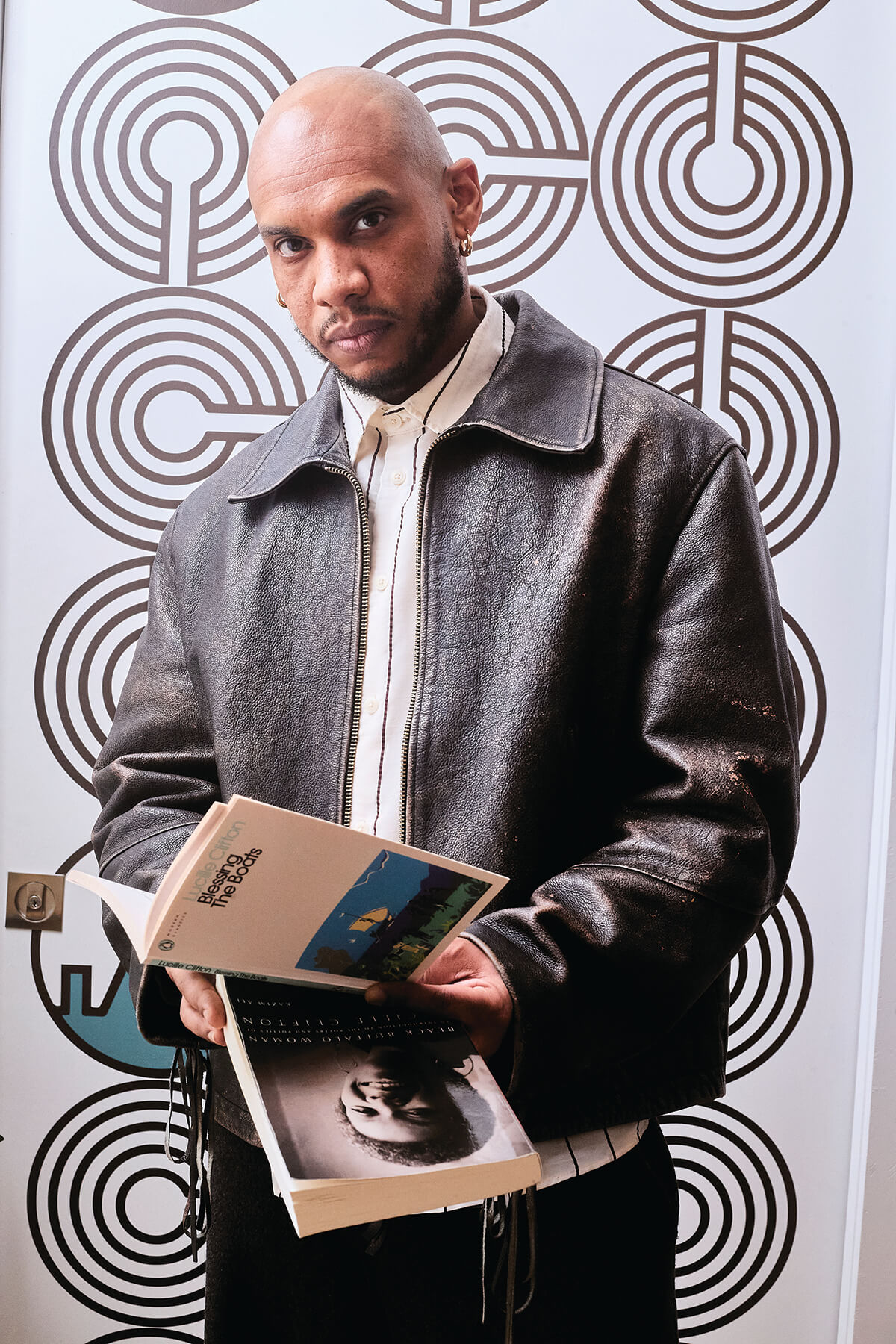

For most of my 20s, I worked in Baltimore as a celebrated musician, poet, and cultural curator, producing events such as the legendary Kahlon dance party at The Crown. The past few years, I moved away, earning a master’s degree at Brown University, taking my attention away from my hometown. But after graduation, I came back, and for the first time in my artistic life, noticed something truly different here. A whole host of new Black-led cultural spaces have been erected while I was gone, including The Last Resort Artist Retreat, where I was an artist-in-residence last summer.

On top of that, a boost of creative transplants from other cities were now settling down here. Groundwork has been laid for new initiatives supporting young artists. And all the while, a number of Black creatives with local ties—Amy Sherald, for instance—have become household names.

With all these ingredients, it felt that the promise of a Black arts renaissance was finally materializing in Baltimore again. Like the 1920s Harlem Renaissance, the 1930s Chicago Renaissance, and the Black Arts Movement in cities like New York, Detroit, and the Bay Area through the 1970s, we might just be becoming the next great epicenter for Black American artists.

“This is not really something new for Baltimore,” says Victoria Adams-Kennedy, one of the leaders of Charm City Cultural Cultivation (CCCC), a new nonprofit based in Waverly and founded by her brother, Baltimore native and internationally acclaimed artist Derrick Adams, which serves as an umbrella for the family’s creative projects, including the Last Resort just up the street. “It’s almost like it’s coming home.”

Like the 1920s Harlem Renaissance, the 1930s Chicago Renaissance, and the Black Arts Movement in cities like New York, Detroit, and the Bay Area through the 1970s, we might just be becoming the next great epicenter for Black American artists.

In addition to shepherding CCCC and being the mother of one of my closest friends (best-selling author and arts writer Lawrence Burney of True Laurels), Adams Kennedy is a self-published novelist and has been creating space for Black women writers in Baltimore through her Zora’s Den group, established in 2017. She got the idea during a class on the Black Arts Movement as an undergraduate at University of Baltimore, also my alma mater.

“We talked about how it was the creative arm of the Black Power Movement,” says Adams-Kennedy, 62, pointing to a famous photograph of women from this era—writer Alice Walker, novelist Toni Morrison, and poet June Jordan. At the time, she says, she had not seen women like herself taking up space and forging a sisterhood in Baltimore. “When I saw that picture, it crystallized that this was something I would like to see now.”

She says there’s a reason Zora’s Den, currently housed in CCCC, is specifically for Black women. “Because there’s a certain dialogue that takes place when it’s just us. There’s a certain kind of ownership of our stories when it’s just us. There’s a certain language we use when it’s just us, without having to be apologetic or to stop and explain.”

Even in a predominantly Black city, it’s a hard truth that institutions have not historically felt accessible and inclusive for Black creatives in this way. As an English major at UB, all my professors were white, and as a Black Baltimore native who also happens to be gay, it never felt like my writing was validated, supported, or understood, a sentiment shared by my fellow Black students.

Today, some establishments, like the Baltimore Museum of Art, are making strides, but citywide there’s still a ways to go. Some of that change is coming from the creation of new physical spaces, like Zora’s Den, which will open its own brick-and-mortar near the Last Resort in the new Solar House later this year. When you speak to local artists, space comes up time and again as the most important need. We need space to convene, to perform, to practice joy—and just to vibe.

What is available is limited, despite a city full of vacant buildings, and underground venues are always at risk of closing or being shut down. Even in an arts district like Station North, there are stretches of empty spaces between its independent galleries, music venues, nightlight spots, and shops, leaving the artistic ecosystem feeling incomplete.

Adams-Kennedy’s brother might be at the forefront of filling in the gaps for Black artists in Baltimore. Now based in Brooklyn, Derrick Adams has nonetheless been coming home and pouring his art-world success into physical spaces like the Last Resort—a beautiful, cloud-colored home filled with guest rooms, communal spaces, and a sprawling sculpture garden.

Opened in 2023, it not only serves as a venue for artist residencies like mine, but also offers a whole range of programming, from exhibitions and workshops to conversations for and by Black creatives. Down the street, his CCCC headquarters is also home to the Black Baltimore Digital Database, a repository for local Black history, featuring a physical gallery, online archive, and public workspace that displays photographs of Black Baltimore families.

Plus, Adams is collaborating on the future Sock Factory in Midway, a communal creative space that will house artist workspaces, and recently joined other artists in purchasing the Mt. Royal Tavern, an affordable bar frequented by creatives of all kinds in Mid-Town Belvedere.

“Baltimore is made up of so much promise, but with the lack of resources, sometimes promise dries up, because people don’t believe in it anymore,” says his sister, Adams-Kennedy. “If you show that something is achievable, that it can—that you can—achieve it, that wakes up hope and inspiration in people.”

Another promising new space is The Clifton House in West Baltimore, home of legendary poet Lucille Clifton, Maryland’s former Poet Laureate, and her educator activist husband, Fred. Opened in 2021, the venue now carries on its late owners’ legacies, providing artistic development opportunities like mentorships, workshops, and readings for underrepresented creatives in Baltimore. Their executive director, Joël Díaz, is a New York native who moved here in 2023.

“One of my first impressions was that people are deeply protective of this city and their communities, which is a beautiful thing—they’re looking out for one another,” he says. “My goal is that, when people walk in the house, they feel nourished, they feel more possible in their artistry, and then leave lighter than how they entered.”

Given The Clifton House’s history, Díaz is excited to see the Black literary scene blossoming in Baltimore, pointing to the success of the CityLit Project, run by Carla DuPree. He’d love to see additional support for these artists, like bringing back the Baltimore Poet Laureate designation—especially after local spoken-word artist and Black Arts District executive director Lady Brion was recently named the state’s Poet Laureate—and offering monetary incentives for both artists and the creative spaces that advocate for them.

“A lot of deep integration is happening on the ground,” he says, “but we also need the support of the city.”

“One of my first impressions was that people are deeply protective of this city and their communities, which is a beautiful thing—they’re looking out for one another,” says Diaz. “My goal is that, when people walk into The Clifton House, they feel nourished, they feel more possible in their artistry, and then leave lighter than how they entered.”

Financial support is another top need expressed by local artists, as it helps them find studio space, purchase materials, or just afford the time to create (most work a day job or two). And many feel their holistic value to the city is often underappreciated. For years, musicians, painters, and filmmakers have done incredible PR to combat the negative reputation of Baltimore, and yet that love has not always felt reciprocated from City Hall.

Last summer, Mayor Brandon Scott announced a whopping $4.6-billion budget, with only $2 million of that earmarked for the creation of a new Mayor’s Office of Art, Culture, and Entertainment (MOACE) following chaos at the Baltimore Office of Promotion & the Arts. How far that money will go remains to be seen. There are several city-sponsored grants available now, such as the Creative Baltimore Fund and the annual Janet & Walter Sondheim Artscape Prize, as well as those from the Maryland State Arts Council and other arts-related organizations like the Greater Baltimore Cultural Alliance’s Baker Artist Awards and the Robert W. Deutsch Foundation’s Rubys. But many artists say the application process feels inaccessible, with some not even knowing these opportunities exist.

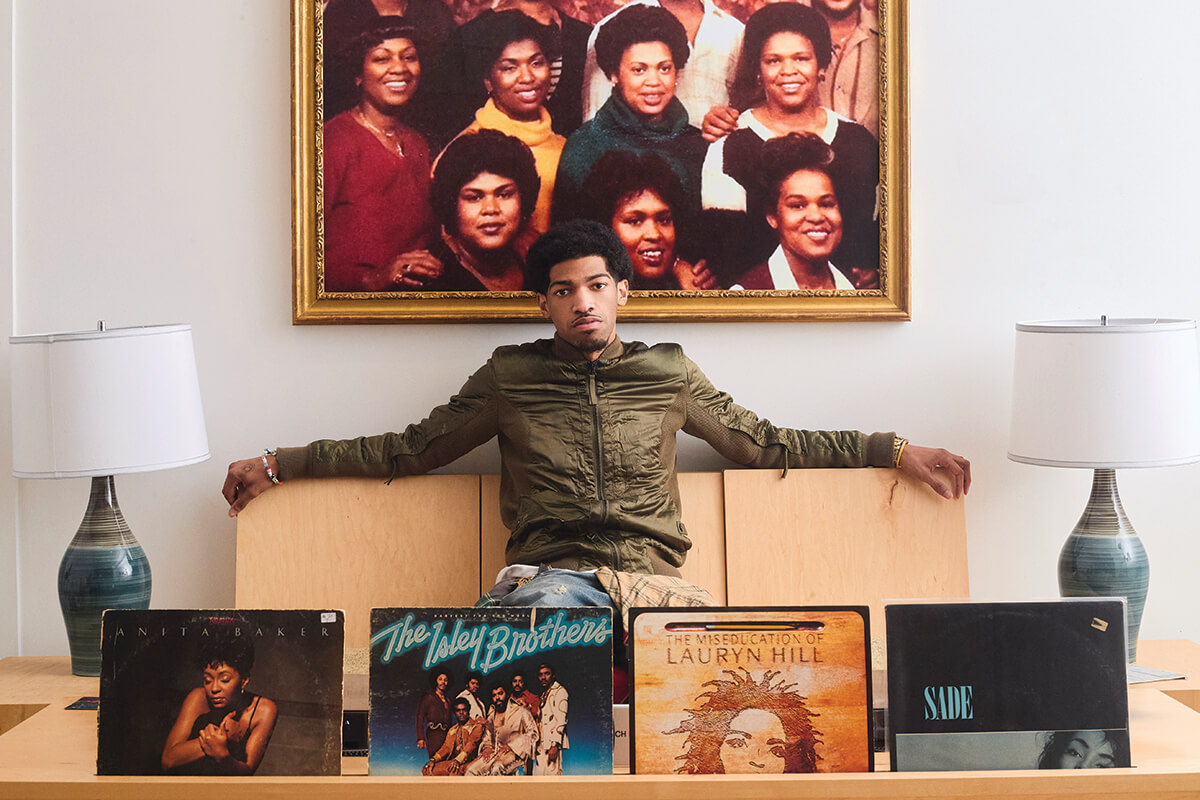

One artist who’s had success on that front, though, is local musician John Tyler. He recently teamed up with the aforementioned Black Arts District, located on that famous stretch of Pennsylvania Avenue, designated one of the state’s official arts and entertainment districts in 2019, to host his Love Groove Festival. As someone who performed in a rap collective on Belair Road and caught both punk shows in the Hampden skate park and DIY sets at the CopyCat Building, the 26-year-old Tyler had noticed the silos of Baltimore’s various music scenes.

“Everything was very separate and segregated,” says the Hoes Heights-raised Baltimore Design School alum. “I just loved all the different artists and felt we needed to build our own platform to showcase our work in a bodacious way. Because at that time, at least from my perspective, we had Artscape and AFRAM and they were bringing out artists from D.C., New York, and California to come perform. But it was like, dang, how come nobody from here is getting put on? It’s so many amazing folks already right here. Let’s just make our own thing.”

In the years since, Love Groove has grown from a small concert into an annual blowout, platforming everyone from up-and-coming local acts to hometown stars like TT The Artist and Serpentwithfeet. Along the way, Tyler has obtained both huge sponsorships and support from the city, including financial backing, festival barricades, and trash pickup. He’s grateful for their help but admits resources could be more widely shared.

“I definitely think the city can do more…There’s so many different festivals that need money, that need resources they aren’t getting. And I do think there could be a better job [establishing] these partnerships.”

Linzy Jackson III, the new MOACE director, acknowledges the perceived disconnect between the city and its artists, and is already working to amend that. To improve trust and communication, his team intends to host listening sessions, is considering ways to improve grant opportunities, and will be hiring a nightlife coordinator to support hubs like the Black Arts District.

“Our job is to make sure that there’s no red tape and that artists feel supported,” says Jackson.

For him, the overall goal is to bolster a creative economy in Baltimore through new investment, infrastructure, and policies, with artist visibility and economic sustainability being a key focus. He points to the new Inviting Light public art installations in Station North, curated by Adams and funded with the help of a $1-million grant from Bloomberg Philanthropies, as an example of visionary partnerships they’re aspiring to in the years ahead.

“I don’t think a Black arts renaissance is approaching, I think we’re in it, with Black artists, curators, and producers not just creating work, but shaping the narrative and public spaces in real time,” says Jackson. “Our role is to make sure that the momentum isn’t just temporary, but supported long-term.”

“Baltimore is made up of so much promise, but with the lack of resources, sometimes promise dries up, because people don’t believe in it anymore,” says Adams-Kennedy. “If you show that something is achievable, that wakes up hope and inspiration.”

As much as investing in the future is crucial, part of a strong foundation for Black artists also lies in access to the past. Deyane Moses is a curator, archivist, and artist from the D.C. area, who, since moving here in 2017 to attend the Maryland Institute College of Art, has played a crucial role in documenting Baltimore’s Black history. There, she founded the Maryland Institute Black Archives to preserve stories of the school’s Black artists and, out of that, launched Tom Miller Week, an annual celebration to honor the legacy of its late namesake painter, who grew up in Sandtown-Winchester.

Now, as the director of programs and partnerships at Afro Charities, she’s taking that work one step further, establishing a physical archive for The Baltimore Afro American, the oldest family-run Black newspaper in the United States, at the Upton Mansion in West Baltimore. She’s noticed a growing cross-generational, cross-discipline, even cross-institutional collaboration that’s contributing to this new energy in Baltimore, pointing to elders like art historian Leslie King-Hammond and multidisciplinary artist Joyce J. Scott as vital resources.

“I’m seeing so much collaboration,” says Moses, 39. “I think people are realizing we don’t need to be reinventing the wheel. It used to be like, ‘We’re doing this, you’re doing that,’…but everybody’s working together now to elevate their ideas and get their goals across. That’s so important, because you can share funds, but also audiences, and then grow [through each other].”

She sees the need for more of a “for-us, by-us” approach, especially in light of the Trump Administration and its recent cuts to funding for diversity and the arts. She mentions the rise of local scholarships and fellowships, like those offered by the Valerie J. Maynard Foundation, founded in 2020 by the late Harlem-born pioneer of Black Arts Movement, who spent much of her life in Baltimore, and the Billie Holiday Center for Liberation Arts at Johns Hopkins University, founded in 2017.

Afro Charities also launched its own youth archivist fellowship in 2022, which it offers in partnership with local arts-education nonprofit Muse 360. She hopes their Upton Mansion project will be one more way of putting Black Baltimore on the map, as well as inspiring people to visit other troves of local history like the Reginald F. Lewis Museum and CCCC. “I’m really excited for all of that, and what’s to come,” says Moses.

That sort of solidarity is especially strong among this next crop of young artists. In 2020, the COVID-19 pandemic brought the local scenes to a grinding halt, so by the time it was safe to gather again, that next generation was more eager than ever to create together.

Both in their mid-20s, Styles Bond, an emerging DJ, and Joshua Slowe, a dynamic photographer, are based in the Hooper House, a creative hub in Charles Village since 2024. There, the duo and other young creatives are making clothes, hosting events, and curating exhibitions, gaining a diverse and growing following.

“We’re really trying to bring people in and get them new experiences,” says Slowe, pointing to their monthly Sunday maker markets under the moniker Triangle Office. “We’re just trying to activate this space as much as we can and invite others in.”

Adds Bond, “That’s how we can help build on what came before and cultivate into the future. A lot of people love coming through here. It’s becoming a meeting place. And slowly each year, it’s attracting more artists.”

Around the city, both have noticed an influx of out-of-town visitors. Artist Mickalene Thomas frequents the Last Resort. Actress Lena Waithe is partnering with Center Stage. And more and more transplants are moving here, too; Baltimore is still known for its affordability, especially compared to New York and Los Angeles, as well as its authenticity.

Of course, whenever there’s an arts boom like this, gentrification also drives out locals, especially Black and brown folks who spent years investing in the arts.

“So much is being cooked up right now that’ll probably be ready in the next five years, but the big thing is, how do the people who live here get to benefit from it?” says Bond, who’s well aware that many artists think they have to leave Baltimore to reach their potential. “We talk with ourselves, like, ‘Yo, staying is also super beneficial.’ But we gotta look long term.”

That sort of dreaming is happening downstairs at the Hooper House, too. On the first floor, Mama Koko’s is a bustling new bar with art-covered walls that, since opening in 2024, has quickly become the go-to space to connect over coffee and cocktails for artists, creatives, and other cultural figures—including its namesake inspiration, the mother of co-owner Angola Selassie.

On weekends, it’s bustling with good vibrations and, in doing so, fills a void, as few nightlife spaces are dedicated to fostering artistic eccentricity for Black Baltimore.

“I hope for Mama Koko’s to continue to be a hub for community, for artists, for everyone,” says co-owner Ayo Hogans, 48. “It’s been good to see people have a space to come out to and just be free.”

“We’re not just thinking dollars and cents…we didn’t want this to be a transactional spot,” says Selassie, 49. “We wanted to be a place for relationships. A literal watering hole, where everyone gathers.”

Born in California, he moved to Baltimore as a child, where his mother quickly became friends with other Black elders, like Womb-Work’s Rashida Forman-Bey and drummer Baba Kauna Mujamal, which has helped him contextualize this current moment as a continuation of previous cycles.

“You know, the Harlem Renaissance was sparked by folks who had just come up off the plantations into the big city,” says Selassie, noting that trailblazing eras of Black art, like hip-hop, often emerged in response to the conditions of Black American life. “Right now is post-Obama, post-COVID, late-stage capitalism, and we’re seeing artists of this time making dope work, too.”

He names the Black-run film collective Lalibela, based in Remington and co-created by local filmmaker Elissa Blount Moorhead, as one example. “And the momentum is growing,” says Hogans.

Everyone feels it. Right now, there really is a cultural and creative uptick happening in this city. And at the same time, there are honest and difficult dialogues that need to continue for it to last. Artists will always do what they have to in order to create. But Baltimore, particularly those with financial, cultural, and political capital, as well as the powers that be, should not wait until they blow up to support them.

“Cities have to create their own arts scenes,” says Adams-Kennedy. “Everybody has a culture. We have Baltimore culture. We have Black Baltimore culture. But it needs to be cultivated—and celebrated.”

She thinks about how, in this moment, at arts spaces like CCCC, experienced Black artists are now gathering and connecting with familiar faces they’ve seen at other events happening around the city, including her own granddaughter looking up to sculptor Murjoni Merriweather.

In that moment, “Something happens,” says Adams-Kennedy. “The community is being built.”

This essay is dedicated to my late grandfather, Frank Webb Eaton.